Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Occup Environ Med > Volume 28; 2016 > Article

- Research Article Association between urinary 3-phenoxybenzoic acid and body mass index in Korean adults: 1st Korean National Environmental Health Survey

- Minsang Yoo, Youn-Hee Lim,, Taeshik Kim, Dongwook Lee, Yun-Chul Hong,,

-

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2016;28:2.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40557-015-0079-7

Published online: January 13, 2016

Department of Preventive Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Environmental Health Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Institute of Environmental Medicine, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea

© Yoo et al. 2016

Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Abstract

-

Background According to US-EPA report, the use of pyrethrins and pyrethroids has increased during the past decade, and their area of use included not only in agricultural settings, but in commerce, and individual household. It is known that urinary 3-PBA, major metabolite of pyrethroid, have some associations with health effect in nervous and endocrine system, however, there’s no known evidence that urinary 3-PBA have associations with obesity.

-

Method We used data of 3671 participants aged above 19 from the Korean National Environmental Health Survey in 2009–2011. In our analysis, multivariate piece-wise regression and logistic regression analysis were used to investigate the association between urinary 3-PBA (3-Phenoxybenzoic Acid) and BMI.

-

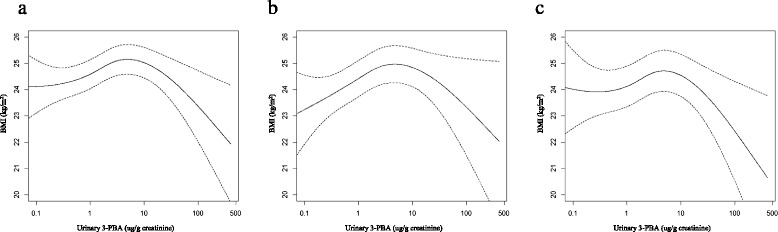

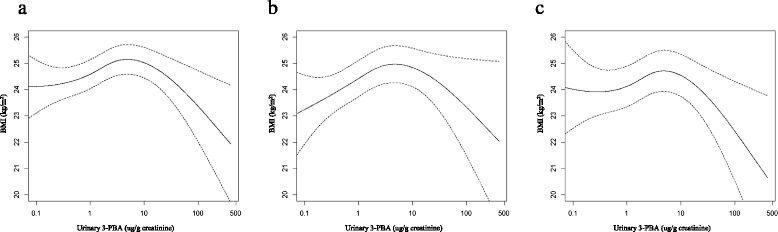

Result Log-transformed level of urinary 3-PBA had significantly positive association with BMI at the low-level range of exposure (p < 0.0001), and opposite associations were observed at the high level exposure (p = 0.04) after adjusting covariates. In piece-wise regression analysis, the flexion point that changes direction of the associations was at around 4 ug/g creatinine of urinary 3-PBA. As quintiles based on concentration of urinary 3-PBA increased to Q4, the ORs for prevalence of overweight (BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2) were increased, and the OR of Q5 was lower than that of Q4 (OR = 1.810 for Q4; OR = 1.483 for Q5). In the analysis using obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) as outcome variable, significant associations were observed between obesity and quintiles of 3-PBA, however, there were no differences between the OR of Q5 and that of Q4 (OR = 1.659 for Q4; OR = 1.666 for Q5).

-

Conclusion Our analysis suggested that low-level of pyrethroid exposure has positive association with BMI, however, there is an inverse relationship above the urinary 3-PBA level at 4 ug/g creatinine.

-

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40557-015-0079-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

-

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Authors’ contributions

Study conception and design: YC Hong, MS Yoo; Acquisition of data: MS Yoo; Analysis and interpretation of data: YC Hong, MS Yoo, YH Lim, TS Kim, DW Lee; Drafting of manuscript: MS Yoo; Critical revision: YC Hong. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

NOTES

- 1. Grube A, Donaldson D, Kiely T, Wu L. Pesticides industry sales and usage. 2011, Washington, DC: US EPA.

- 2. Cha ES, Jeong M, Lee WJ. Agricultural pesticide usage and prioritization in South Korea. J Agromedicine 2014;19(3):281–93. 10.1080/1059924X.2014.917349. 24959760.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Vijverberg HP, van der Zalm JM, van den Bercken J. Similar mode of action of pyrethroids and DDT on sodium channel gating in myelinated nerves. Nature 1982;295(5850):601–3. 10.1038/295601a0. 6276777.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 4. Aldridge W. An assessment of the toxicological properties of pyrethroids and their neurotoxicity. CRC Crit Rev Toxicol 1990;21(2):89–104. 10.3109/10408449009089874.Article

- 5. Quiros-Alcala L, Mehta S, Eskenazi B. Pyrethroid pesticide exposure and parental report of learning disability and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in U.S. children: NHANES 1999-2002. Environ Health Perspect 2014;122(12):1336–42. 25192380.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Narahashi T. Neurophysiological effects of insecticides. Handb of pesticide toxicol 2001;1:335–50. 10.1016/B978-012426260-7.50015-X.Article

- 7. Barr DB, Olsson AO, Wong LY, Udunka S, Baker SE, Whitehead RD, et al. Urinary concentrations of metabolites of pyrethroid insecticides in the general U.S. population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118(6):742–8. 10.1289/ehp.0901275. 20129874.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Wax PM, Hoffman RS. Fatality associated with inhalation of a pyrethrin shampoo. Clin Toxicol 1994;32(4):457–60.Article

- 9. Wagner SL. Fatal asthma in a child after use of an animal shampoo containing pyrethrin. West J Med 2000;173(2):86. 10.1136/ewjm.173.2.86. 10924422.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Oulhote Y, Bouchard MF. Urinary metabolites of organophosphate and pyrethroid pesticides and behavioral problems in Canadian children. Environ Health Perspect 2013;121(11-12):1378–84. 24149046.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Xue Z, Li X, Su Q, Xu L, Zhang P, Kong Z, et al. Effect of synthetic pyrethroid pesticide exposure during pregnancy on the growth and development of infants. Asia Pac J Public Health 2013;25(4 Suppl):72S–9. 23966607.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 12.

- 13. Lee D-H, Lind PM, Jacobs DR, Salihovic S, van Bavel B, Lind L. Polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides in plasma predict development of type 2 diabetes in the elderly the prospective investigation of the vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS) study. Diabetes Care 2011;34(8):1778–84. 10.2337/dc10-2116. 21700918.PubMedPMC

- 14. Lee D-H, Steffes MW, Sjödin A, Jones RS, Needham LL, Jacobs DR Jr. Low dose organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls predict obesity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance among people free of diabetes. PLoS ONE 2011;6(1):e15977. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015977. 21298090.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Welshons WV, Thayer KA, Judy BM, Taylor JA, Curran EM, Vom Saal FS. Large effects from small exposures. I. Mechanisms for endocrine-disrupting chemicals with estrogenic activity. Environ Health Perspect 2003;111(8):994. 10.1289/ehp.5494. 12826473.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Lagarde F, Beausoleil C, Belcher SM, Belzunces LP, Emond C, Guerbet M, et al. Non-monotonic dose-response relationships and endocrine disruptors: a qualitative method of assessment. Environ Heal 2015;14(1):13. 10.1186/1476-069X-14-13.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 17. Lee D-H, Porta M, Jacobs DR Jr, Vandenberg LN. Chlorinated persistent organic pollutants, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev 2014;35(4):557–601. 10.1210/er.2013-1084. 24483949.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 18. Becker K, Seiwert M, Angerer J, Kolossa-Gehring M, Hoppe H-W, Ball M, et al. GerES IV pilot study: assessment of the exposure of German children to organophosphorus and pyrethroid pesticides. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2006;209(3):221–33. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2005.12.002. 16461005.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Wielgomas B, Nahorski W, Czarnowski W. Urinary concentrations of pyrethroid metabolites in the convenience sample of an urban population of Northern Poland. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2013;216(3):295–300. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2012.09.001. 23021951.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Ueyama J, Kimata A, Kamijima M, Hamajima N, Ito Y, Suzuki K, et al. Urinary excretion of 3-phenoxybenzoic acid in middle-aged and elderly general population of Japan. Environ Res 2009;109(2):175–80. 10.1016/j.envres.2008.09.006. 19081088.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Qi X, Zheng M, Wu C, Wang G, Feng C, Zhou Z. Urinary pyrethroid metabolites among pregnant women in an agricultural area of the Province of Jiangsu, China. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2012;215(5):487–95. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.12.003. 22218106.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Kim B, Jung A, Yun D, Lee M, Lee M-R, Choi Y-H, et al. Association of urinary 3-phenoxybenzoic acid levels with self-reported depression symptoms in a rural elderly population in Asan, South Korea. Environ Health Toxicol 2015;30:e2015002. 10.5620/eht.e2015002. 25997450.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 23. Gladen BC, Ragan NB, Rogan WJ. Pubertal growth and development and prenatal and lactational exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dichlorodiphenyl dichloroethene. J Pediatr 2000;136(4):490–6. 10.1016/S0022-3476(00)90012-X. 10753247.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Glynn AW, Granath F, Aune M, Atuma S, Darnerud PO, Bjerselius R, et al. Organochlorines in Swedish women: determinants of serum concentrations. Environ Health Perspect 2003;111(3):349. 10.1289/ehp.5456. 12611665.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Hue O, Marcotte J, Berrigan F, Simoneau M, Doré J, Marceau P, et al. Plasma concentration of organochlorine compounds is associated with age and not obesity. Chemosphere 2007;67(7):1463–7. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.10.033. 17126879.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Karmaus W, Osuch JR, Eneli I, Mudd LM, Zhang J, Mikucki D, et al. Maternal levels of dichlorodiphenyl-dichloroethylene (DDE) may increase weight and body mass index in adult female offspring. Occup Environ Med 2009;66(3):143–9. 10.1136/oem.2008.041921. 19060027.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Patandin S, Koopman-Esseboom C, De Ridder MA, Weisglas-Kuperus N, Sauer PJ. Effects of environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins on birth size and growth in Dutch children. Pediatr Res 1998;44(4):538–45. 10.1203/00006450-199810000-00012. 9773843.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Hertz-Picciotto I, Charles MJ, James RA, Keller JA, Willman E, Teplin S. In utero polychlorinated biphenyl exposures in relation to fetal and early childhood growth. Epidemiology 2005;16(5):648–56. 10.1097/01.ede.0000173043.85834.f3. 16135941.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW, Humphrey HE. Effects of exposure to PCBs and related compounds on growth and activity in children. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1990;12(4):319–26. 10.1016/0892-0362(90)90050-M. 2118230.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Dirinck E, Jorens PG, Covaci A, Geens T, Roosens L, Neels H, et al. Obesity and persistent organic pollutants: possible obesogenic effect of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls. Obesity 2011;19(4):709–14. 10.1038/oby.2010.133. 20559302.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 31. Lee D-H, Lee I-K, Porta M, Steffes M, Jacobs D Jr. Relationship between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among non-diabetic adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetologia 2007;50(9):1841–51. 10.1007/s00125-007-0755-4. 17624515.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 32. Lee M-R, Kim JH, Choi Y-H, Bae S, Park C, Hong Y-C. Association of bisphenol A exposure with overweight in the elderly: a panel study. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2015;22(12):9370–7. 10.1007/s11356-015-4087-5.ArticlePDF

- 33. Boucher J, Boudreau A, Atlas E. Bisphenol A induces differentiation of human preadipocytes in the absence of glucocorticoid and is inhibited by an estrogen-receptor antagonist. Nut Diab 2014;4(1):e102. 10.1038/nutd.2013.43.ArticlePDF

- 34. Wada K, Sakamoto H, Nishikawa K, Sakuma S, Nakajima A, Fujimoto Y, et al. Life style-related diseases of the digestive system: endocrine disruptors stimulate lipid accumulation in target cells related to metabolic syndrome. J Pharmacol Sci 2007;105(2):133–7. 10.1254/jphs.FM0070034. 17928741.ArticlePubMed

- 35. MacKay H, Patterson ZR, Khazall R, Patel S, Tsirlin D, Abizaid A. Organizational effects of perinatal exposure to bisphenol-A and diethylstilbestrol on arcuate nucleus circuitry controlling food intake and energy expenditure in male and female CD-1 mice. Endocrinology 2013;154(4):1465–75. 10.1210/en.2012-2044. 23493373.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 36. Hugo ER, Brandebourg TD, Woo JG, Loftus J, Alexander JW, Ben-Jonathan N. Bisphenol A at environmentally relevant doses inhibits adiponectin release from human adipose tissue explants and adipocytes. Environ Health Perspect 2008;116(12):1642–7. 10.1289/ehp.11537. 19079714.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 37. Nunez A, Kannan K, Giesy J, Fang J, Clemens L. Effects of bisphenol A on energy balance and accumulation in brown adipose tissue in rats. Chemosphere 2001;42(8):917–22. 10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00196-X. 11272914.ArticlePubMed

- 38. Ishmael J, Litchfield M. Chronic toxicity and carcingenic evaluation of permethrin in rats and mice. Toxicol Sci 1988;11(1):308–22. 10.1093/toxsci/11.1.308.Article

- 39. Parker C, Patterson D, Van Gelder G, Gordon E, Valerio M, Hall W. Chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity evaluation of fenvalerate in rats. J Toxicol Environ Health 1984;13(1):83–97. 10.1080/15287398409530483. 6716513.ArticlePubMed

- 40. Oswal A, Yeo G. Leptin and the control of body weight: a review of its diverse central targets, signaling mechanisms, and role in the pathogenesis of obesity. Obesity 2010;18(2):221–9. 10.1038/oby.2009.228. 19644451.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 41. Klok M, Jakobsdottir S, Drent M. The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obes Rev 2007;8(1):21–34. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00270.x. 17212793.ArticlePubMed

- 42. Sahu A. Leptin signaling in the hypothalamus: emphasis on energy homeostasis and leptin resistance. Front Neuroendocrinol 2003;24(4):225–53. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.10.001. 14726256.ArticlePubMed

- 43. Wallner‐Liebmann S, Koschutnig K, Reishofer G, Sorantin E, Blaschitz B, Kruschitz R, et al. Insulin and hippocampus activation in response to images of high‐calorie food in normal weight and obese adolescents. Obesity 2010;18(8):1552–7. 10.1038/oby.2010.26. 20168310.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 44. Davidson TL, Chan K, Jarrard LE, Kanoski SE, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC. Contributions of the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex to energy and body weight regulation. Hippocampus 2009;19(3):235–52. 10.1002/hipo.20499. 18831000.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 45. Davidson TL, Kanoski SE, Schier LA, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC. A potential role for the hippocampus in energy intake and body weight regulation. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2007;7(6):613–6. 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.008. 18032108.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 46. Hossain MM, Suzuki T, Sato I, Takewaki T, Suzuki K, Kobayashi H. The modulatory effect of pyrethroids on acetylcholine release in the hippocampus of freely moving rats. Neurotoxicology 2004;25(5):825–33. 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.01.002. 15288513.ArticlePubMed

- 47. Chen H, Xiao J, Hu G, Zhou J, Xiao H, Wang X. Estrogenicity of organophosphorus and pyrethroid pesticides. J Toxic Environ Health A 2002;65(19):1419–35. 10.1080/00984100290071243.Article

- 48. Garey J, Wolff MS. Estrogenic and antiprogestagenic activities of pyrethroid insecticides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998;251(3):855–9. 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9569. 9790999.ArticlePubMed

- 49. vom Saal FS, Nagel SC, Coe BL, Angle BM, Taylor JA. The estrogenic endocrine disrupting chemical bisphenol A (BPA) and obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2012;354(1):74–84. 10.1016/j.mce.2012.01.001. 22249005.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 50. Heindel JJ. Endocrine disruptors and the obesity epidemic. Toxicol Sci 2003;76(2):247–9. 10.1093/toxsci/kfg255. 14677558.ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Appendix

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- Bifenthrin causes disturbance in mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetic system in human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293)

Anwesha Das, Madhusudan Das, Nirvika Paul, Srilagna Chatterjee, Kunal Sarkar, Sarbashri Bank, Jit Sarkar, Biswabandhu Bankura, Debraj Roy, Krishnendu Acharya, Sudakshina Ghosh

Environmental Pollution.2025; 368: 125707. CrossRef - Pyrethroids have become a barrier to the daily existence of molluscs (Review)

Raja Saha, Sangita Maiti Dutta

Journal of Hazardous Materials Letters.2025; 6: 100144. CrossRef - Biological Diversity Associated with Pesticides Residues in Certain Egyptian Watercourses

Asmaa Abdel-Motleb, Rania M. Abd El-Hamid, Sara S. M. Sayed

Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology.2025; 88(4): 419. CrossRef - Maternal exposure to beta-Cypermethrin disrupts placental development by dysfunction of trophoblast cells from oxidative stress

Xiaoli Tang, Yanqing Geng, Rufei Gao, Zhuxiu Chen, Xinyi Mu, Yan Zhang, Xin Yin, Yidan Ma, Xuemei Chen, Fangfang Li, Junlin He

Toxicology.2024; 504: 153796. CrossRef - The Teratogenic Effect of Dimefluthrin-Based Mosquito Coils on Pregnant Mice (Mus musculus L.)

Efrizal, Chika Afrilia Ikbal, Robby Jannatan

Malaysian Applied Biology.2024; 53(1): 83. CrossRef - Association of 3-Phenoxybenzoic Acid Exposure during Pregnancy with Maternal Outcomes and Newborn Anthropometric Measures: Results from the IoMum Cohort Study

Juliana Guimarães, Isabella Bracchi, Cátia Pinheiro, Nara Moreira, Cláudia Coelho, Diogo Pestana, Maria Prucha, Cristina Martins, Valentina Domingues, Cristina Delerue-Matos, Cláudia Dias, Luís Azevedo, Conceição Calhau, João Leite, Carla Ramalho, Elisa K

Toxics.2023; 11(2): 125. CrossRef - The diabetogenic effects of pesticides: Evidence based on epidemiological and toxicological studies

Yile Wei, Linping Wang, Jing Liu

Environmental Pollution.2023; 331: 121927. CrossRef - Comparison between pollutants found in breast milk and infant formula in the last decade: A review

I. Martín-Carrasco, P. Carbonero-Aguilar, B. Dahiri, I.M. Moreno, M. Hinojosa

Science of The Total Environment.2023; 875: 162461. CrossRef - Pyrethroid pesticides: An overview on classification, toxicological assessment and monitoring

Ayaz Ahamad, Jitendra Kumar

Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances.2023; 10: 100284. CrossRef - Kinetics of uptake and depuration of synthetic pyrethroid insecticides in manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum)

Manni Wu, Xianming Tang, Ce Sun, Jingjing Miao, Qiaoqiao Wang, Luqing Pan

Environmental Science and Pollution Research.2023; 30(30): 76246. CrossRef - The association of prenatal and childhood pyrethroid pesticide exposure with school-age ADHD traits

Kyung-Shin Lee, Youn-Hee Lim, Young Ah Lee, Choong Ho Shin, Bung-Nyun Kim, Yun-Chul Hong, Johanna Inhyang Kim

Environment International.2022; 161: 107124. CrossRef - Research and Application of In Situ Sample-Processing Methods for Rapid Simultaneous Detection of Pyrethroid Pesticides in Vegetables

Bo Mei, Weiyi Zhang, Meilian Chen, Xia Wang, Min Wang, Yinqing Ma, Chunyan Zhu, Bo Deng, Hongkang Wang, Siwen Shen, Jinrong Tong, Mengfeng Gao, Yiyi Han, Dongsheng Feng

Separations.2022; 9(3): 59. CrossRef - Mixtures modeling identifies heavy metals and pyrethroid insecticide metabolites associated with obesity

Hai Duc Nguyen, Hojin Oh, Won Hee Jo, Ngoc Hong Minh Hoang, Min-Sun Kim

Environmental Science and Pollution Research.2022; 29(14): 20379. CrossRef - Resistance to Cypermethrin Is Widespread in Cattle Ticks (Rhipicephalus microplus) in the Province of Punjab, Pakistan: In Vitro Diagnosis of Acaricide Resistance

Zia ud Din Sindhu, Muhammad Usman Naseer, Ali Raza, Bilal Aslam, Javed Ahmad, Rao Zahid Abbas, Muhammad Kasib Khan, Muhammad Imran, Muhammad Arif Zafar, Baharullah Khattak

Pathogens.2022; 11(11): 1293. CrossRef - Pesticide residues levels in raw cow's milk and health risk assessment across the globe: A systematic review

Ali Boudebbouz, Sofiane Boudalia, Meriem Imen Boussadia, Yassine Gueroui, Safia Habila, Aissam Bousbia, George K. Symeon

Environmental Advances.2022; 9: 100266. CrossRef - Pyrethroids exposure induces obesity and cardiometabolic diseases in a sex-different manner

Lei Zuo, Li Chen, Xia Chen, Mingliang Liu, Haiyan Chen, Guang Hao

Chemosphere.2022; 291: 132935. CrossRef - The effects of chemical mixtures on lipid profiles in the Korean adult population: threshold and molecular mechanisms for dyslipidemia involved

Hai Duc Nguyen, Hojin Oh, Min-Sun Kim

Environmental Science and Pollution Research.2022; 29(26): 39182. CrossRef - Exposure to fenvalerate and tebuconazole exhibits combined acute toxicity in zebrafish and behavioral abnormalities in larvae

Chunlian Yao, Lan Huang, Changsheng Li, Dongxing Nie, Yajie Chen, Xuanjun Guo, Niannian Cao, Xuefeng Li, Sen Pang

Frontiers in Environmental Science.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - The stereoselective metabolic disruption of cypermethrin on rats by a sub-acute study based on metabolomics

Sijia Gu, Quan Zhang, Jinping Gu, Cui Wang, Mengjie Chu, Jing Li, Xunjie Mo

Environmental Science and Pollution Research.2022; 30(11): 31130. CrossRef - Magnetic solid-phase extraction of pyrethroid and neonicotinoid insecticides separately in environmental water samples based on alkaline or acidic group-functionalized mesoporous silica

Rui Han, Fei Wang, Chuanfeng Zhao, Meixing Zhang, Shihai Cui, Jing Yang

The Analyst.2022; 147(9): 1995. CrossRef - Effects of prenatal exposure to pyrethroid pesticides on neurodevelopment of 1-year- old children: A birth cohort study in China

Zhiye Qi, Xiaoxiao Song, Xia Xiao, Kek Khee Loo, May C. Wang, Qinghua Xu, Jie Wu, Shuqi Chen, Ying Chen, Lingling Xu, Yan Li

Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety.2022; 234: 113384. CrossRef - The endangered African Great Ape: Pesticide residues in soil and plants consumed by Mountain Gorillas (Gorilla beringei) in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, East Africa

Chemonges Amusa, Jessica Rothman, Silver Odongo, Henry Matovu, Patrick Ssebugere, Deborah Baranga, Mika Sillanpää

Science of The Total Environment.2021; 758: 143692. CrossRef - The concomitant effects of self-limiting insect releases and behavioural interference on patterns of coexistence and exclusion of competing mosquitoes

Maisie Vollans, Michael B. Bonsall

Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.2021; 288(1951): 20210714. CrossRef - Association between pyrethroid exposure and cardiovascular disease: A national population-based cross-sectional study in the US

Qingping Xue, An Pan, Ying Wen, Yichao Huang, Da Chen, Chun-Xia Yang, Jason HY Wu, Jie Yang, Jay Pan, Xiong-Fei Pan

Environment International.2021; 153: 106545. CrossRef - Urinary 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) concentration and pulmonary function in children: A National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2012 analysis

Peipei Hu, Weiwei Su, Angela Vinturache, Haoxiang Gu, Chen Cai, Min Lu, Guodong Ding

Environmental Pollution.2021; 270: 116178. CrossRef - Exposure to multiclass pesticides among female adult population in two Chinese cities revealed by hair analysis

Feng-Jiao Peng, Emilie M. Hardy, Sakina Mezzache, Nasrine Bourokba, Paul Palazzi, Natali Stojiljkovic, Philippe Bastien, Jing Li, Jeremie Soeur, Brice M.R. Appenzeller

Environment International.2020; 138: 105633. CrossRef - Contamination of pyrethroids in agricultural soils from the Yangtze River Delta, China

Fucai Deng, Jianteng Sun, Rongni Dou, Xiaolong Yu, Zi Wei, Chunping Yang, Xiangfeng Zeng, Lizhong Zhu

Science of The Total Environment.2020; 731: 139181. CrossRef - Environmental exposure to pyrethroid pesticides in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults and children: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2012

Hans-Joachim Lehmler, Derek Simonsen, Buyun Liu, Wei Bao

Environmental Pollution.2020; 267: 115489. CrossRef - Predictors of Urinary Pyrethroid and Organophosphate Compound Concentrations among Healthy Pregnant Women in New York

Arin A. Balalian, Xinhua Liu, Eva Laura Siegel, Julie Beth Herbstman, Virginia Rauh, Ronald Wapner, Pam Factor-Litvak, Robin Whyatt

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.2020; 17(17): 6164. CrossRef - The optimization of pyrethroid simultaneous analysis in tropical soil of Indonesian tea plantation: Preliminary study

M Ariyani, M M Pitoi, R Yusiasih, H Maulana, T A Koesmawati

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science.2020; 483(1): 012037. CrossRef - Impact of pesticide exposure on adipose tissue development and function

Robert M. Gutgesell, Evangelia E. Tsakiridis, Shanza Jamshed, Gregory R. Steinberg, Alison C. Holloway

Biochemical Journal.2020; 477(14): 2639. CrossRef - Thermal effects on tissue distribution, liver biotransformation, metabolism and toxic responses in Mongolia racerunner (Eremias argus) after oral administration of beta-cyfluthrin

Zikang Wang, Li Chen, Luyao Zhang, Wenjun Zhang, Yue Deng, Rui Liu, Yinan Qin, Zhiqiang Zhou, Jinling Diao

Environmental Research.2020; 185: 109393. CrossRef - Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and anthropometric measures of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Carolina Martins Ribeiro, Bruna Teles Soares Beserra, Nadyellem Graciano Silva, Caroline Lourenço Lima, Priscilla Roberta Silva Rocha, Michella Soares Coelho, Francisco de Assis Rocha Neves, Angélica Amorim Amato

BMJ Open.2020; 10(6): e033509. CrossRef - Purification of pyrethrins from flowers of Chrysanthemum cineraraeflium by high-speed counter-current chromatography based on coordination reaction with silver nitrate

Heng Lu, Heng Zhu, Hongjing Dong, Lanping Guo, Tianyu Ma, Xiao Wang

Journal of Chromatography A.2020; 1613: 460660. CrossRef - β‐Cypermethrin Alleviated the Inhibitory Effect of Medium from RAW 264.7 Cells on 3T3‐L1 Cell Maturation into Adipocytes

Bingnan He, Xia Wang, Xini Jin, Zimeng Xue, Yinhua Ni, Jianbo Zhu, Caiyun Wang, Yuanxiang Jin, Zhengwei Fu

Lipids.2020; 55(3): 251. CrossRef - Deltamethrin impact in a cabbage planted soil: Degradation and effect on microbial community structure

Idalina Bragança, Ana P. Mucha, Maria P. Tomasino, Filipa Santos, Paulo C. Lemos, Cristina Delerue-Matos, Valentina F. Domingues

Chemosphere.2019; 220: 1179. CrossRef - Vortex‐assisted Emulsification Microextraction for the Determination of Pyrethroids in Mushroom

Wenfei Zhao, Xu Jing, Mingchang Chang, Junlong Meng, Cuiping Feng

Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society.2019; 40(10): 943. CrossRef - The relationship of urinary 3-phenoxybenzoic acid concentrations in utero and during childhood with adiposity in 4-year-old children

Kyung-Shin Lee, Young Ah Lee, Yun Jeong Lee, Choong ho Shin, Youn-Hee Lim, Yun-Chul Hong

Environmental Research.2019; 172: 446. CrossRef - Urinary concentrations of permethrin metabolites in US Army personnel in comparison with the US adult population, occupationally exposed cohorts, and other general populations

Alexis L. Maule, Matthew M. Scarpaci, Susan P. Proctor

International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health.2019; 222(3): 355. CrossRef - Correlation between the Repeated Dermal Exposure to Deltamethrin and Excretion of 3-PBA in Rats

Areumnuri Kim, Kyongmi Chon, Byung-Jun Park, Byeong-Chul Moon, Byung-Seok Kim, Min-Kyoung Paik

The Korean Journal of Pesticide Science.2018; 22(4): 370. CrossRef - Pyrethroid pesticide residues in the global environment: An overview

Wangxin Tang, Di Wang, Jiaqi Wang, Zhengwen Wu, Lingyu Li, Mingli Huang, Shaohui Xu, Dongyun Yan

Chemosphere.2018; 191: 990. CrossRef

- Figure

- Related articles

-

- Relationship between the use of hair products and urine benzophenone-3: the Korean National Environmental Health Survey (KoNEHS) cycle 4

- Association between serum perfluoroalkyl substances concentrations and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among Korean adults: a cross-sectional study using the National Environmental Health Survey cycle 4

- Environment-wide association study of elevated liver enzymes: results from the Korean National Environmental Health Survey 2018–2022

- Relationship between shellfish consumption and urinary phthalate metabolites: Korean National Environmental Health Survey (KoNEHS) cycle 3 (2015-2017)

Fig. 1

| Concentration of urinary 3-PBA (ug/g Creatinine) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Geometric mean | Geometric SD | |

| Total | 3671 | 1.83 | 2.71 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1838 | 1.59 | 2.66 |

| Female | 1833 | 2.10 | 2.70 |

| Age | |||

| 19–29 | 448 | 0.95 | 2.41 |

| 30–39 | 696 | 1.25 | 2.50 |

| 40–49 | 835 | 1.69 | 2.37 |

| 50–59 | 902 | 2.42 | 2.46 |

| 60≤ | 790 | 2.91 | 2.78 |

| Region | |||

| Metropolitan area and Gangwon | 1467 | 1.68 | 2.71 |

| Chungchong | 458 | 1.85 | 2.59 |

| Honam | 466 | 2.39 | 2.77 |

| Yongnam | 1185 | 1.86 | 2.72 |

| Jeju | 95 | 1.36 | 1.99 |

| Current Smoking | |||

| No | 2803 | 1.95 | 2.73 |

| Yes | 868 | 1.47 | 2.56 |

| Current Drinking | |||

| No | 1478 | 2.16 | 2.72 |

| Yes | 2193 | 1.63 | 2.66 |

| Regular Exercise | |||

| No | 2048 | 1.83 | 2.76 |

| Yes | 1060 | 1.93 | 2.65 |

| Irregular exercise | 563 | 1.64 | 2.60 |

| Education | |||

| Middle school | 1113 | 2.90 | 2.69 |

| High school | 1245 | 1.80 | 2.51 |

| College | 1313 | 1.25 | 2.47 |

| BMI(kg/m2) | |||

| < 18.5 | 100 | 1.28 | 2.88 |

| 18.5 to < 23 | 1232 | 1.63 | 2.79 |

| 23 to < 25 | 886 | 1.85 | 2.68 |

| 25 ≤ | 1453 | 2.05 | 2.60 |

| Use of Mosquitocide | |||

| No | 826 | 1.58 | 2.63 |

| Only summer | 2798 | 1.90 | 2.73 |

| All year around | 36 | 2.06 | 2.22 |

| Summer, winter | 11 | 1.83 | 2.10 |

| Job Classification | |||

| Skilled agricultural and fishery workers | 384 | 2.71 | 3.05 |

| aIndoor worker | 1103 | 1.48 | 2.54 |

| bOutdoor worker | 846 | 1.78 | 2.44 |

| cOthers | 1338 | 1.97 | 2.80 |

| Flexion point of Log-transformed urinary 3-PBA | Below flexion point | After flexion point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-estimate (SE) | P value | Beta-estimate (SE) | P value | ||

| Model 1 | 1.4 | 0.5830 (0.0769) | < 0.0001 | −0.2137 (0.1679) | 0.20 |

| Model 2 | 1.5 | 0.4038 (0.0786) | < 0.0001 | −0.3609 (0.1792) | 0.04 |

| Model 3 | 1.4 | 0.4004 (0.0820) | < 0.0001 | −0.3443 (0.1679) | 0.04 |

| < Overweight > | ||||||

| Quintiles of 3-PBA | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | |

| Q1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Q2 | 1.481 | 1.114–1.970 | 1.311 | 0.980–1.755 | 1.339 | 0.993–1.806 |

| Q3 | 1.841 | 1.395–2.428 | 1.535 | 1.143–2.061 | 1.503 | 1.113–2.031 |

| Q4 | 2.256 | 1.715–2.968 | 1.813 | 1.346–2.441 | 1.810 | 1.329–2.464 |

| Q5 | 2.020 | 1.534–2.662 | 1.508 | 1.103–2.060 | 1.483 | 1.066–2.062 |

| < Obesity > | ||||||

| Quintiles of 3-PBA | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | |

| Q1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Q2 | 1.384 | 1.056–1.813 | 1.263 | 0.955–1.671 | 1.277 | 0.970–1.682 |

| Q3 | 1.840 | 1.408–2.405 | 1.613 | 1.218–2.137 | 1.606 | 1.228–2.100 |

| Q4 | 1.945 | 1.454–2.603 | 1.656 | 1.201–2.282 | 1.659 | 1.211–2.273 |

| Q5 | 2.100 | 1.605–2.748 | 1.715 | 1.274–2.308 | 1.666 | 1.245–2.230 |

aIndoor worker : Legislators, senior officials and managers, Professionals, Clerks, Service workers and shop and market sales workers

bOutdoor worker : Craft and related trades workers, Plant and machine operators and assemblers, Elementary occupations, Armed forces

cOthers : Housewives, Students, Unknown

*Model 1 : Crude

Model 2 : Sex, age adjusted

Model 3 : Sex, age, region, current smoking status, current drinking status, regular exercise, education, use of mosquitocide, and job classification adjusted

*Range of quintiles: Q1 0.032–0.797, Q2 0.800–1.386, Q3 1.387–2.256, Q4 2.257–4.009, Q5 4.027–261.252

Model 1 : Crude

Model 2 : Sex, age adjusted

Model 3 : Sex, age, region, current smoking status, current drinking status, regular exercise, education, use of mosquitocide, and job classification adjusted

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite