Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Occup Environ Med > Volume 33; 2021 > Article

- Research Article The relationship between working hours and the intention to quit smoking in male office workers: data from the 7th Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2016–2017)

-

Eui Hyek Choi

, Dae Hwan Kim

, Dae Hwan Kim , Ji Young Ryu

, Ji Young Ryu

-

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2021;33:e13.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2021.33.e13

Published online: May 4, 2021

Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- Correspondence: Ji Young Ryu. Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital, 875 Haeundae-ro, Haeundae-gu, Busan 48108, Korea. lyou77@paik.ac.kr

Copyright © 2021 Korean Society of Occupational & Environmental Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

-

Background The intention to quit smoking is one of the most important factors in smoking cessation. Long working hours is also a constant issue, and many studies have shown an association between the working hours and diseases, including cardiovascular and gastrointestinal diseases. This study evaluated the relationship between working hours and the intention to quit smoking among Korean male office workers, and blue collar workers for comparison.

-

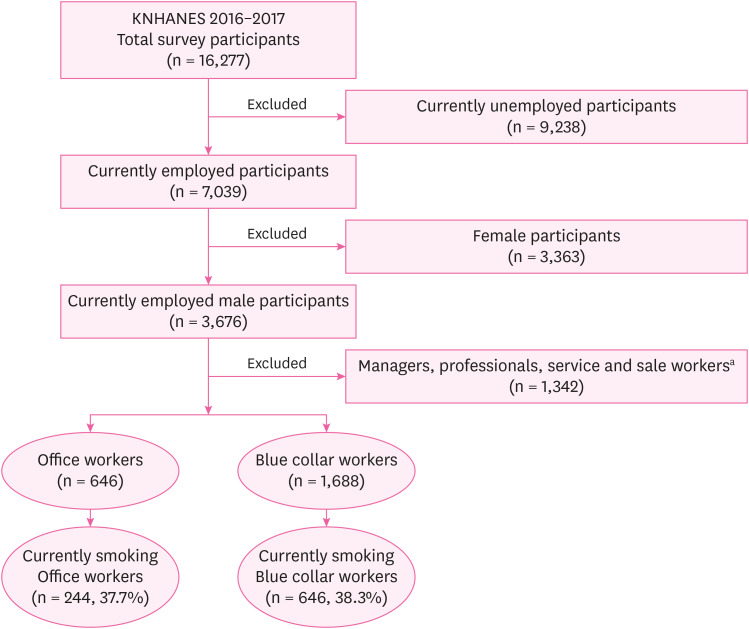

Methods This study was based on the Seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2016–2017). A total of 1,389 male workers were smokers, and then office workers and blue collar workers were selected. Logistic regression was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) for the intention to quit smoking according to smoking-related characteristics and working hours after adjusting for age group, body mass index (kg/m2), marital status, household income (quartile), educational level, drinking, exercise, smoking-related characteristics (smoking initiation age, smoking amount, and attempt to quit smoking more than 1day in the past year) and working hours.

-

Results The percentage of workers who had the intention to quit smoking in 6 months was higher in office workers (38.9% for office workers and 29.4% for blue collars, p = 0.017). Blue collar workers had higher percentages of workers who worked more than 52 hours per week (19.8% for office workers and 38.9% for blue collar workers, p < 0.001). Logistic regression analysis showed that working > 52 hours per week was significantly associated with a lower intention to quit smoking within 6 months among male office workers (OR = 0.30, 95% confidence interval = 0.14–0.66).

-

Conclusions Working more than 52 hours per week was positively related with a lower intention to quit smoking among currently smoking male office workers. Further studies are needed considering more work-related variables such as job stress and physical load.

BACKGROUND

METHODS

Flowchart assessing eligible subjects in KNHANES (2016–2017).

RESULTS

General characteristics, smoking related characteristics and working hours of study samples (smoking male office workers and blue collar workers) in comparison

Intention to quit smoking according to general characteristics among smoking male office workers

Intention to quit smoking according to general characteristics among smoking male blue collar workers

Logistic regression analysis (ORs and 95% CIs) of the intention to quit smoking within 6 months according to smoking-related characteristics and working hours of smoking male office workers and blue collar workers

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

BMI

CI

IRB

KNHANES

KSCO

LAAM

OR

-

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Availability of data and materials: The datasets analyzed during the current study are available on Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/sub03/sub03_02_02.do.

-

Author Contributions:

NOTES

- 1. World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2017: Monitoring Tobacco Use and Prevention Policies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- 2. Cahn Z, Drope J, Hamill S, Islami F, Liber A, Nargis N, et al. The Tobacco Atlas: Sixth Edition. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society and Vital Strategies; 2018.

- 3. Jung GJ. The influence of smoking on the health of Korean citizens: prediction of the number of smokers and smoking-related deaths. Tob Free 2019;20:6–15.

- 4. Lee SM, Paik JW, Hyeon GR, Gang HR. Socio-economic Effects of Major Health Risk Factors and Effectiveness of Regulatory Policy - Korea. Wonju: The Korean National Health Insurance - National Insurance Policy Institute; 2015.

- 5. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004;328(7455):1519. 15213107.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Hughes JR. Motivating and helping smokers to stop smoking. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18(12):1053–1057. 14687265.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983;51(3):390–395. 6863699.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Topa G, Moriano JA. MORIANO LEON. Theory of planned behavior and smoking: meta-analysis and SEM model. Subst Abuse Rehabil 2010;1:23–33. 24474850.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q, Yong HH, McNeill A, Fong GT, et al. Individual-level predictors of cessation behaviours among participants in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii83–iii94. 16754952.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Kenford SL, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Wetter D, Baker TB. Predicting smoking cessation. Who will quit with and without the nicotine patch. JAMA 1994;271(8):589–594. 8301790.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Buell P, Breslow L. Mortality from coronary heart disease in California men who work long hours. J Chronic Dis 1960;11(6):615–626. 13805687.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Spurgeon A, Harrington JM, Cooper CL. Health and safety problems associated with long working hours: a review of the current position. Occup Environ Med 1997;54(6):367–375. 9245942.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Choi SY, Kim TH, Park DH. A study on job stress and MSDs(Musculoskeletal Disorders) of workers at automobile manufacturing industry. Journal of the Korean of Safety 2005;20:202–211.

- 14. Kim GS. Work stress and related factors among married working women in the manufacturing sector. J Korean Public Health Nurs 2003;17(2):212–213.

- 15. Yoon CG, Bae KJ, Kang MY, Yoon JH. Is suicidal ideation linked to working hours and shift work in Korea? J Occup Health 2015;57(3):222–229. 25752659.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 16. Kim J. Association between working conditions and smoking status among Korean employees. Korean J Occup Health Nurs 2015;24(3):204–213.Article

- 17. Lee J, Lee I. A comparison of characteristics between success group and failure group of 1-year continuous smoking abstinence in young adult and middle-aged male workers: with focus on the first-year analysis of Korean Cross-sectional Survey. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs 2016;27(2):27.ArticlePDF

- 18. Shin DY, Jang YK, Lee JH, Wee JH, Chun DH. Relationship with smoking and dyslipidemia in Korean adults. JKSRNT 2017;8(2):73–79.Article

- 19. Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Cornuz J. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2007;298(22):2654–2664. 18073361.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Ryu H, Kim Y, Lee J, Yoon SJ, Cho JH, Wong E, et al. Office workers' risk of metabolic syndrome-related indicators: a 10-year cohort study. West J Nurs Res 2016;38(11):1433–1447. 27330047.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 21. Ryu H, Chin DL. Factors associated with metabolic syndrome among Korean office workers. Arch Environ Occup Health 2017;72(5):249–257. 27285063.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Eriksen W. Work factors and smoking cessation in nurses' aides: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2005;5:142. 16379672.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 23. Shields M. Long working hours and health. Health Rep 1999;11(2):33–48. 10618741.PubMed

- 24. Lee K, Suh C, Kim JE, Park JO. The impact of long working hours on psychosocial stress response among white-collar workers. Ind Health 2017;55(1):46–53. 27498571.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Kikuchi H, Odagiri Y, Ohya Y, Nakanishi Y, Shimomitsu T, Theorell T, et al. Association of overtime work hours with various stress responses in 59,021 Japanese workers: retrospective cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2020;15(3):e0229506–0229506. 32126094.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 26. Parrott AC. Cigarette-derived nicotine is not a medicine. World J Biol Psychiatry 2003;4(2):49–55. 12692774.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smoking. A longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55(2):161–166. 9477930.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Ranjit A, Latvala A, Kinnunen TH, Kaprio J, Korhonen T. Depressive symptoms predict smoking cessation in a 20-year longitudinal study of adult twins. Addict Behav 2020;108:106427. 32361366.ArticlePubMed

- 29. McKee SA, Sinha R, Weinberger AH, Sofuoglu M, Harrison EL, Lavery M, et al. Stress decreases the ability to resist smoking and potentiates smoking intensity and reward. J Psychopharmacol 2011;25(4):490–502. 20817750.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 30. Muraven M, Baumeister RF. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol Bull 2000;126(2):247–259. 10748642.ArticlePubMed

- 31. Ham DC, Przybeck T, Strickland JR, Luke DA, Bierut LJ, Evanoff BA. Occupation and workplace policies predict smoking behaviors: analysis of national data from the current population survey. J Occup Environ Med 2011;53(11):1337–1345. 21988795.PubMedPMC

- 32. Albertsen K, Hannerz H, Borg V, Burr H. Work environment and smoking cessation over a five-year period. Scand J Public Health 2004;32(3):164–171. 15204176.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 33. Giovino GA, Trosclair A. The prevalence of selected cigarette smoking behaviors by occupational class in the United States. Work, Smoking and Health. A NIOSH Scientific Workshop. Washington, D.C.: NIOSH; 2000.

- 34. Sorensen G, Emmons K, Stoddard AM, Linnan L, Avrunin J. Do social influences contribute to occupational differences in quitting smoking and attitudes toward quitting? Am J Health Promot 2002;16(3):135–141. 11802258.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 35. Ahn HR. Factors Associated with Intention to Quit Smoking in Community-dwelling Male Adult Smokers. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs 2015;26(4):26.Article

- 36. Kim SJ, Ko KD, Suh HS, Kim KK, Hwang IC, Kim SH, et al. Factors associated with intention to quit smoking in Korean adult males: the sixth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2013–2014. Korean J Fam Pract 2017;7(2):276–280.Article

- 37. Fagan P, Augustson E, Backinger CL, O'Connell ME, Vollinger RE Jr, Kaufman A, et al. Quit attempts and intention to quit cigarette smoking among young adults in the United States. Am J Public Health 2007;97(8):1412–1420. 17600244.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 38. Ryu SY, Shin JH, Kang MG, Park J. Factors associated with intention to quit smoking among male smokers in 13 communities in Honam region of Korea: 2010 community health survey. Korean J Health Educ Promot 2011;28(2):75–85.

- 39. Hymowitz N, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lynn WR, Pechacek TF, Hartwell TD. Predictors of smoking cessation in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tob Control 1997;6(Suppl 2):S57–S62.ArticlePubMedPMC

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- Tobacco cessation in Northeast India: The impact of mass media on changing habits

Dimpal Pathak, Naina Purkayastha, Himani Sharma, Partha J. Hazarika, Jiten Hazarika

Population Medicine.2025; 7(April): 1. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and diet quality and patterns: A latent profile analysis of a nationally representative sample of Korean workers

Seong-Uk Baek, Jong-Uk Won, Yu-Min Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon

Preventive Medicine.2024; 180: 107890. CrossRef - Long Working Hours and Unhealthy Lifestyles of Workers: A Protocol for a Scoping Review

Seong-Uk Baek, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Merits.2024; 4(4): 431. CrossRef - Association between weekly working hours and risky alcohol use: A 12-year longitudinal, nationwide study from South Korea

Seong-Uk Baek, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Psychiatry Research.2023; 326: 115325. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and cigarette smoking, leisure-time physical activity, and risky alcohol use: Findings from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2014–2021)

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Preventive Medicine.2023; 175: 107691. CrossRef - Association between job satisfaction and current smoking and change in smoking behavior: a 16‐year longitudinal study in South Korea

Seong‐Uk Baek, Won‐Tae Lee, Min‐Seok Kim, Myeong‐Hun Lim, Jin‐Ha Yoon, Jong‐Uk Won

Addiction.2023; 118(11): 2118. CrossRef - Psychiatric symptoms and intentions to quit smoking: How regularity and volume of cigarette consumption moderate the relationship

Xiaochen Yang, Lanchao Zhang, Hao Lin, Haoxiang Lin, Wangnan Cao, Chun Chang

Tobacco Induced Diseases.2023; 21(June): 1. CrossRef - Changes in the Health Indicators of Hospital Medical Residents During the Four-Year Training Period in Korea

Ji-Sung Ahn, Seunghyeon Cho, Won-Ju Park

Journal of Korean Medical Science.2022;[Epub] CrossRef

- Figure

- Related articles

-

- Relationship between long-term PM2.5 exposure and myopia prevalence in adults: analysis of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey–Air Pollution Linked Data, 2020

- Exploring the impact of age and socioeconomic factors on health-related unemployment using propensity score matching: results from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2015–2017)

- Relationship between visual display terminal working hours and headache/eyestrain in Korean wage workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the sixth Korean Working Conditions Survey

Fig. 1

| Variables | Office workers (n = 244) | Blue collar (n = 646) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | < 0.001 | ||||

| 19–44 | 154 (67.9) | 240 (44.0) | |||

| 45–64 | 83 (30.7) | 322 (48.6) | |||

| ≥ 65 | 7 (1.5) | 84 (7.4) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.968 | ||||

| < 25 | 136 (58.5) | 381 (58.3) | |||

| ≥ 25 | 108 (41.5) | 265 (41.7) | |||

| Marital status | 0.312 | ||||

| Cohabitation | 187 (72.8) | 475 (68.7) | |||

| LAAM or single | 57 (27.2) | 171 (31.3) | |||

| Household income (quartile) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Q1 (low) | 7 (3.7) | 75 (8.0) | |||

| Q2 | 43 (17.4) | 194 (28.8) | |||

| Q3 | 87 (36.5) | 222 (38.2) | |||

| Q4 (high) | 107 (42.3) | 154 (25.0) | |||

| Education | < 0.001 | ||||

| ≤ High school | 79 (32.6) | 503 (75.9) | |||

| ≥ College | 165 (67.4) | 143 (24.1) | |||

| Drinking | 0.995 | ||||

| No | 58 (24.1) | 164 (24.2) | |||

| Yes | 183 (75.9) | 463 (75.8) | |||

| Exercise | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 153 (61.4) | 522 (78.5) | |||

| Yes | 91 (38.6) | 124 (21.5) | |||

| Smoking-related characteristics | |||||

| Intention to quit smoking | 0.017 | ||||

| No | 151 (61.1) | 452 (70.6) | |||

| Yes | 93 (38.9) | 194 (29.4) | |||

| Smoking initiation age (years) | 0.028 | ||||

| < 19 | 97 (41.2) | 306 (50.6) | |||

| ≥ 19 | 147 (58.8) | 340 (49.4) | |||

| Smoking amount (cigarettes/day) | 0.025 | ||||

| 1–10 | 100 (41.5) | 249 (38.5) | |||

| 11–20 | 133 (54.2) | 329 (50.9) | |||

| > 21 | 11 (4.3) | 68 (10.6) | |||

| Attempt to quit smoking | 0.905 | ||||

| No | 108 (43.5) | 281 (44.1) | |||

| Yes | 136 (56.5) | 365 (55.9) | |||

| Work-related characteristics | |||||

| Working hours | < 0.001 | ||||

| ≤ 52 | 186 (80.2) | 332 (61.1) | |||

| > 52 | 41 (19.8) | 213 (38.9) | |||

| Variables | Intention to quit smoking | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| General characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 0.267 | ||||

| 19–44 | 58 (37.9) | 96 (62.1) | |||

| 45–64 | 30 (39.6) | 53 (60.4) | |||

| > 65 | 5 (74.0) | 3 (26.0) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.248 | ||||

| < 25 | 55 (42.2) | 81 (57.8) | |||

| ≥ 25 | 38 (34.4) | 70 (65.6) | |||

| Marital status | 0.650 | ||||

| Cohabitation | 72 (40.0) | 115 (60.0) | |||

| LAAM or single | 21 (36.1) | 36 (63.9) | |||

| Household income (quartile) | 0.717 | ||||

| Q1 (low) | 4 (59.0) | 3 (41.0) | |||

| Q2 | 16 (38.3) | 27 (61.7) | |||

| Q3 | 32 (37.9) | 55 (62.1) | |||

| Q4 (high) | 41 (38.3) | 66 (61.7) | |||

| Education | 0.236 | ||||

| ≤ High school | 28 (33.1) | 51 (66.9) | |||

| ≥ College | 65 (41.8) | 100 (58.2) | |||

| Drinking | 0.127 | ||||

| No | 17 (29.6) | 41 (70.4) | |||

| Yes | 76 (42.5) | 107 (57.5) | |||

| Exercise | 0.835 | ||||

| Yes | 57 (38.4) | 96 (61.6) | |||

| No | 36 (39.8) | 55 (60.2) | |||

| Smoking-related characteristics | |||||

| Smoking initiation age (years) | 0.076 | ||||

| ≥ 19 | 33 (31.7) | 64 (68.3) | |||

| < 19 | 60 (44.0) | 87 (56.0) | |||

| Smoking amount (cigarettes/day) | 0.103 | ||||

| 1–10 | 48 (47.3) | 52 (52.7) | |||

| 11–20 | 41 (33.5) | 92 (66.5) | |||

| ≥ 21 | 4 (27.5) | 7 (72.5) | |||

| Attempt to quit smoking | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 66 (50.1) | 70 (49.9) | |||

| No | 27 (24.4) | 81 (75.6) | |||

| Work-related characteristics | |||||

| Working hours | 0.013 | ||||

| ≤ 52 | 74 (42.4) | 112 (57.6) | |||

| > 52 | 11 (21.5) | 30 (78.5) | |||

| Variables | Intention to quit smoking | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| General characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 0.562 | ||||

| 19–44 | 73 (31.5) | 167 (68.5) | |||

| 45–64 | 93 (27.4) | 229 (72.6) | |||

| > 65 | 28 (29.7) | 56 (70.3) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.957 | ||||

| < 25 | 109 (29.3) | 272 (70.7) | |||

| ≥ 25 | 85 (29.5) | 180 (70.5) | |||

| Marital status | 0.269 | ||||

| Cohabitation | 150 (31.0) | 35 (69.0) | |||

| LAAM or single | 44 (25.8) | 127 (74.2) | |||

| Household income (quartile) | 0.204 | ||||

| Q1 (low) | 31 (41.2) | 44 (58.8) | |||

| Q2 | 52 (26.8) | 142 (73.2) | |||

| Q3 | 64 (31.5) | 158 (68.5) | |||

| Q4 (high) | 47 (25.4) | 107 (74.6) | |||

| Education | 0.737 | ||||

| ≤ High school | 155 (29.8) | 348 (70.2) | |||

| ≥ College | 39 (28.0) | 104 (72.0) | |||

| Drinking | 0.995 | ||||

| No | 51 (29.0) | 113 (71.0) | |||

| Yes | 135 (29.0) | 328 (71.0) | |||

| Exercise | 0.408 | ||||

| Yes | 45 (32.8) | 79 (67.2) | |||

| No | 149 (28.4) | 373 (71.6) | |||

| Smoking-related characteristics | |||||

| Smoking initiation age (years) | 0.425 | ||||

| ≥ 19 | 98 (27.6) | 242 (72.4) | |||

| < 19 | 96 (31.1) | 210 (68.9) | |||

| Smoking amount (cigarettes/day) | 0.002 | ||||

| 1–10 | 101 (38.8) | 148 (61.2) | |||

| 11–20 | 80 (24.1) | 249 (75.9) | |||

| ≥ 21 | 13 (20.6) | 55 (79.4) | |||

| Attempt to quit smoking | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 161 (43.7) | 204 (56.3) | |||

| No | 33 (11.2) | 248 (88.8) | |||

| Work-related characteristics | |||||

| Working hours | 0.167 | ||||

| ≤ 52 | 103 (31.0) | 229 (69.0) | |||

| > 52 | 57 (25.3) | 156 (74.7) | |||

| General characteristics | Office worker (n = 224a) | Blue collar (n = 531b) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |||

| Smoking related characteristics | ||||

| Smoking initiation age (years) | ||||

| ≥ 19 | 1 | 1 | ||

| < 19 | 0.56 (0.29–1.09) | 1.47 (0.91–2.38) | ||

| Smoking amount (cigarettes/day) | ||||

| 1–10 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 11–20 | 0.90 (0.46–1.78) | 0.58 (0.35–0.97) | ||

| > 21 | 1.15 (0.22–6.12) | 0.63 (0.23–1.71) | ||

| Attempt to quit smoking | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 0.36 (0.18–0.71) | 0.14 (0.08–0.25) | ||

| Work-related characteristics | ||||

| Working hours | ||||

| ≤ 52 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 52 | 0.30 (0.14–0.66) | 0.75 (0.48–1.19) | ||

Data are presented as number (weighted%). Total number may vary due to unanswered questionnaires.

BMI: body mass index, LAAM: living alone after marriage.

Data are presented as number (weighted%).

BMI: body mass index, LAAM: living alone after marriage.

Data are presented as number (weighted%).

BMI: body mass index, LAAM: living alone after marriage.

OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval.

aTotal n may vary due to unanswered questionnaires; bAdjusting for age group, body mass index, marital status, household income, educational level, drinking, exercise, smoking initiation age, smoking amount, attempt to quit smoking and working hours.

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite