Abstract

-

Background

Previous reports showed that age and socioeconomic factors mediated health-related unemployment. However, those studies had limitations controlling for confounding factors. This study examines age and socioeconomic factors contributing to health-related unemployment using propensity score matching (PSM) to control for various confounding variables.

-

Methods

Data were obtained from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) from 2015–2017. We applied a 1:1 PSM to align health factors, and examined the association between health-related unemployment and age or socioeconomic factors through conditional logistic regression. The health-related unemployment group was compared with the employment group.

-

Results

Among the 9,917 participants (5,817 women, 4,100 men), 1,182 (853 women, 329 men) were in the health-related unemployment group. Total 911 pairs (629 women pairs and 282 men pairs) were retained after PSM for health factors. The results of conditional logistic regression showed that older age, low individual and household income levels, low education level, receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits and longest-held job characteristics were linked to health-related unemployment, despite having similar health levels.

-

Conclusions

Older age and low socioeconomic status can increase the risk of health-related unemployment, highlighting the presence of age discrimination and socioeconomic inequality. These findings underscore the importance of proactive management strategies aimed at addressing these disparities, which are crucial for reducing the heightened risk of health-related unemployment.

-

Keywords: Health-related unemployment; Propensity score matching; Age; Socioeconomic status

BACKGROUND

As Korea has become an increasingly aging society, health-related unemployment has gained increasing attention. Unemployment can have adverse effects on individuals by causing the deterioration of physical and physiological health.

1,2 Moreover, its effects can extend beyond individuals, affecting society as a whole. Health-related unemployment often results in a reduction in the available labor force, consequently leading to a decline in social vitality or economic growth. Therefore, to prevent these problems, addressing the challenges of health-related unemployment is an essential step.

While the association between unemployment and health is well established, causality remains unclear. Understanding the intricate relationship between health and unemployment poses a challenge because health can act as both a cause, and consequence, of unemployment. Unemployment can cause health problems, whereas poor health can lead to unemployment or hinder reemployment.

3,4 Furthermore, this complex relationship is influenced by multiple factors, including socioeconomic factors, which operate through various mechanisms.

The impact of socioeconomic factors on health-related unemployment has been widely acknowledged. Low socioeconomic factors can heighten the risk of health-related unemployment, despite similar health conditions.

5 Low education, occupation, and income are widely acknowledged as influential factors leading to disability retirement.

6 The types of work and social inequalities, such as gender and ethnicity, have been found to influence the association between health and unemployment.

7

Age is another significant factor contributing to discrimination in unemployment. As aging progresses in many countries and the retirement of elderly workers leads to a loss of labor force, many countries are striving to address age discrimination in the workforce. Negative stereotypes about aging, such as perceptions of reduced competence, physical deterioration, and weakened social connections, are the main factors contributing to age discrimination in the workplace.

8

Previous research has primarily relied on observational studies, creating a challenge in addressing selection bias.

9 A selection bias commonly arises when individuals differ systematically from the population of interest. This discrepancy can lead to a systematic error in the association or outcome, complicating the accurate assessment of outcome disparities between the comparison and experimental groups. Furthermore, without randomization, ensuring that confounding variables are similarly distributed between the comparison and experimental groups is difficult.

To overcome these limitations, several epidemiological analysis methodologies have been developed, of which propensity score matching (PSM) has emerged as a prominent strategy. The propensity score, which is essentially the likelihood of being assigned to the experimental group based on observed covariates, serves as a key component of PSM. Participants with similar propensity scores are paired, whereas unmatched participants are excluded from statistical analyses. Through PSM, differences between the comparison and experimental groups are minimized.

10

This study aimed to investigate the influence of age and socioeconomic factors on health-related unemployment, using PSM to control for confounding health variables. We employed the employment group as comparison group.

METHODS

Participants

Data were obtained from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) VI (2015) and VII (2016–2017), because reasons for unemployment were no longer surveyed since 2018. KNHANES is an annual national health survey designed to evaluate health and health-related activities.

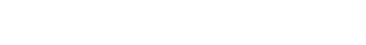

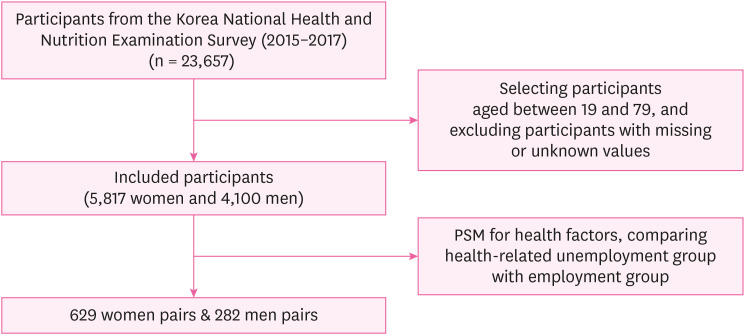

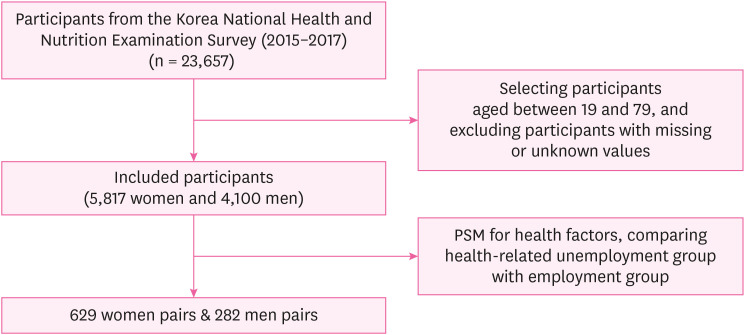

11 We excluded participants aged 80 years and older because all ages above 80 years were recorded as 80 in the survey. After selecting participants and excluding those with missing or unknown values, 9,917 participants (5,817 women and 4,100 men) were included in the main analysis. A flowchart of the participants is shown in

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

Flow chart of study participants.

PSM: propensity score matching.

Measurements

The dependent variable in this study was “health-related unemployment,” which was obtained from the self-reported survey. In the survey, employment status was determined by the question “In the past week, have you worked more than 1 hour for income or worked more than 18 hours as an unpaid family worker? (This includes cases when you were originally employed, but had been working during your temporary leave).” Responses were recorded as “yes” or “no.” Based on these responses, we categorized participants into either the “employment” or unemployment group. Next, the reasons for unemployment were posed to the unemployment group by the question “What is your biggest reason for not working?” The responses were surveyed with seven options: 1) did not feel the need, 2) currently attending school or an educational institution, 3) reached retirement age or in retirement status, 4) health-related reasons, 5) unemployed or job seeking, 6) childcare, caregiving, or other reasons, and 7) other. Among these, participants who chose health-related reasons were classified as the “health-related unemployment group,” whereas the others were categorized as the “other-cause-related unemployment group.”

Independent variables were age group and socioeconomic factors. Age group was divided into 4 categories: 19–34, 35–49, 50–64, and 65–79 years old. Socioeconomic factors included individual and household income levels, education level, receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits, home ownership status, and longest-held job characteristics. Income and education levels were categorized into four categories in the survey, while receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits and home ownership status were evaluated as binary variables. The longest-held job characteristics included category, employment status, and details of employment status. In this study, the category of longest-held job was classified into white-collar, pink-collar, and blue-collar jobs.

Health factors, including health status, lifestyle, medical history, and laboratory findings, were used as covariates for PSM.

Table 1List of variables

|

Category |

Variables |

|

Dependent variable |

Health-related unemployment |

|

Health factors for PSM |

Health status |

EQ-5D score, subjective poor-health, stress perception, unmet health care needs |

|

Lifestyle |

Average sleep time per day (hours), waist circumference (cm), obesity, binge drinking, smoking status, walking activity status, strength training status, aerobic physical activity status, use of dietary supplement |

|

Medical history |

Hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, anemia, myocardial infarction or angina, arthritis, osteoporosis, pulmonary tuberculosis, asthma, thyroid disease, depression, cataract, glaucoma, macular degeneration |

|

Laboratory findings |

AST (IU/L), ALT (IU/L), BUN (mg/dL), eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2), urine protein, urine glucose, urine ketone, urine bilirubin, urine occult blood, urobilinogen |

|

Independent variables |

Age group |

(19–34/35–49/50–64/65–79 years old) |

|

Socioeconomic factors |

Individual and household income levels (upper/upper middle/lower middle/lower), education level (college graduation or more/high school graduation/middle school graduation/elementary school graduation or less), receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits, home insurance status, Longest-held job characteristics: Category (white/pink/blue), employment status (paid/self-employed/unpaid worker), detail of employment status (regular/temporary/daily worker) |

Statistical analyses

We conducted a 1:1 PSM to increase comparability by reducing confounding effects while stratifying patients by gender. Stratifying gender was aimed at balancing gender distribution among groups, given its anticipated impact on socioeconomic disparities in health.

12 Propensity scores were calculated based on health factors to evaluate the influence of age and socioeconomic factors on health-related unemployment. The health-related unemployment group was compared with the employment group.

At first, propensity scores were calculated for both the health-related unemployment and employment groups. Subsequently, a 1:1 PSM was conducted by using a Greedy nearest neighbor matching algorithm, pairing a participant from the health-related unemployment group with a participant from the employment group who had a similar propensity score. Conditional logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess association of age and socioeconomic factors with health-related unemployment in the matched pairs.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.1, utilizing the “MatchIt” package for PSM. A predefined significance level of 0.05 was set for the analyses.

Ethics statement

The present study protocol was exempted from review by the Institutional Review Board of Catholic University College of Medicine (approval No. KC21ZASI0536). Informed consent was submitted by all participants when they were enrolled.

RESULTS

In total, 9,917 participants (5,817 women and 4,100 men) were included in this study. Among them, 1,182 (853 women and 329 men) belonged to the health-related unemployed group, while 5,777 (2,894 women and 2,883 men) were in the employment group.

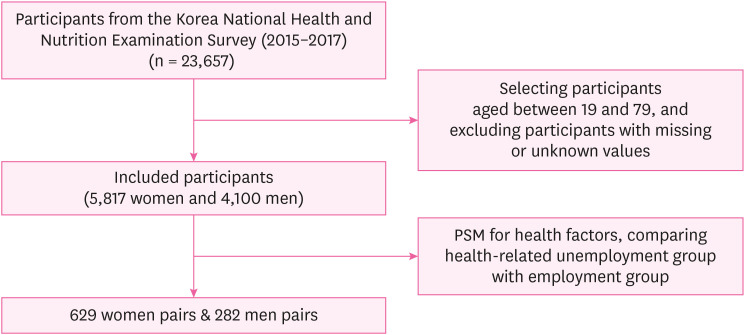

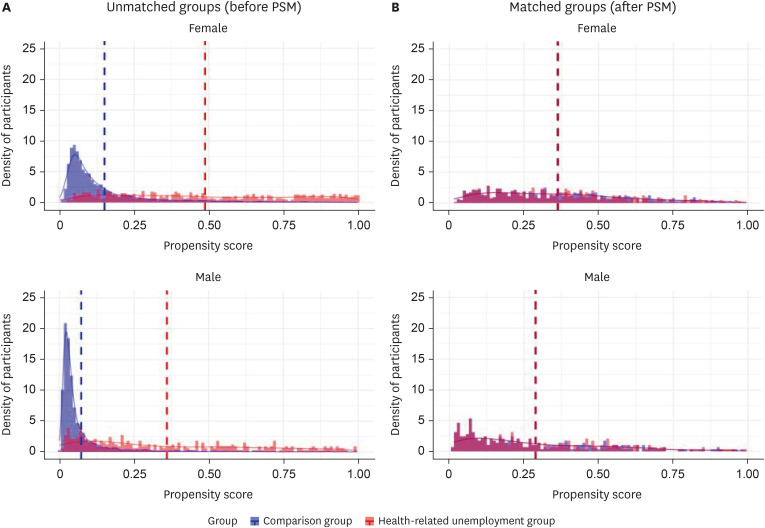

Average propensity scores

Before PSM for health factors, the average propensity scores of the health-related unemployment group (0.49 for women and 0.36 for men) were higher than those of the employment group (0.15 for women and 0.07 for men). After PSM, the mean propensity scores of paired groups were 0.36 for women and 0.29 for men. The average propensity scores for health factors are presented in

Fig. 2. Detailed descriptive statistics of health factors before and after matching can be found in

Supplementary Table 2 for women and

Supplementary Table 3 for men.

Fig. 2

Distribution of propensity score for health factors. (A) Unmatched groups (before PSM) (B) Matched groups (after PSM).

PSM: propensity score matching.

PSM examining association of health-related unemployment with age and socioeconomic factors

After PSM for health factors, 911 pairs (629 women pairs and 282 men pairs) were retained (

Table 2). Among both genders, statistically significant increases in the risk of health-related unemployment were observed in those with older age, low individual and household income levels, low education level and receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits. While the health-related unemployment risk was higher for women in the older age group, it was higher for men among those with low individual and household income levels and receipt of Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits.

Table 2Logistic regression results showing association of health-related unemployment with age and socioeconomic factors

|

Independent variables |

Gender |

|

Women (629 pairs) |

Men (282 pairs) |

|

Age group |

|

|

|

35–49 (vs. 19–34) |

2.22 (1.14–4.59)

|

0.61 (0.25–1.52) |

|

50–64 (vs. 19–34) |

2.66 (1.42–5.29)

|

1.67 (0.78–3.71) |

|

65–79 (vs. 19–34)

|

4.13 (2.21–8.21)

|

2.18 (1.04–4.75)

|

|

Individual income level |

|

|

|

Upper middle (vs. upper) |

1.27 (0.90–1.80) |

0.95 (0.53–1.71) |

|

Lower middle (vs. upper) |

1.30 (0.93–1.83) |

0.82 (0.47–1.45) |

|

Lower (vs. upper)

|

1.77 (1.27–2.46)

|

4.43 (2.61–7.65)

|

|

Household income level |

|

|

|

Upper middle (vs. upper) |

1.17 (0.80–1.71) |

1.26 (0.63–2.55) |

|

Lower middle (vs. upper)

|

1.71 (1.21–2.45)

|

2.31 (1.25–4.41)

|

|

Lower (vs. upper)

|

2.19 (1.56–3.08)

|

8.43 (4.62–16.07)

|

|

Education level |

|

|

|

High school graduation (vs. college graduation or more)

|

1.65 (1.12–2.43)

|

2.09 (1.26–3.52)

|

|

Middle school graduation (vs. college graduation or more)

|

1.98 (1.30–3.05)

|

2.66 (1.50–4.79)

|

|

Elementary school graduation or less (vs. college graduation or more)

|

2.08 (1.47–2.97)

|

3.64 (2.25–5.98)

|

|

Receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits

|

2.00 (1.43–2.82)

|

4.84 (2.94–8.28)

|

|

Home ownership status |

0.94 (0.74–1.20) |

0.60 (0.42–0.86)

|

|

Longest-held job: category |

|

|

|

Pink (vs. white) |

1.32 (0.95–1.82) |

1.14 (0.67–1.94) |

|

Blue (vs. white)

|

1.64 (1.21–2.22)

|

1.90 (1.26–2.88)

|

|

Longest-held job: employment status |

|

|

|

Self-employed worker (vs. paid worker)

|

0.70 (0.52–0.93)

|

0.66 (0.47–0.94)

|

|

Unpaid family worker (vs. paid worker) |

0.64 (0.47–0.85)

|

0.69 (0.17–2.64) |

|

Longest-held job: detail of employment status |

|

|

|

Temporary worker (vs. regular worker) |

1.29 (0.94–1.79) |

3.56 (1.85–7.28)

|

|

Daily worker (vs. regular worker) |

1.56 (0.99–2.47) |

2.21 (1.23–4.05)

|

Sensitivity analysis restricting age under 65

Sensitivity analysis was conducted restricting participants aged between 19 and 64 years, as the upper limit for the working-age population is under 65 years old. After PSM for health factors, 424 pairs (324 women pairs and 100 men pairs) were retained (

Supplementary Table 4). The mean propensity scores of paired groups were 0.28 for women and 0.23 for men. Similar results were shown, indicating the association of health-related unemployment with low individual and household income levels, low education level, receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits and longest-held job characteristics.

DISCUSSION

The results of our analysis showed older age and low socioeconomic factors, including low individual and household income levels, low education level, receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits and being a blue-collar worker, were linked to health-related unemployment after matching propensity scores based on health factors. Gender differences were observed in relation to age, income levels and receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits. While women faced a higher risk of health-related unemployment related to older age, men were more at risk related to lower income levels and receipt of Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits. Taken together, these results reveal an association between health-related unemployment and age as well as socioeconomic factors. The main findings of this study are consistent with those of previous studies.

Even after matching for health factors, older age was associated with health-related unemployment indicating age discrimination. This finding suggests that individuals may be compelled to retire due to health reasons primarily because of their age, despite having similar health conditions. It could imply the presence of conscious or unconscious biases among employers and employees, leading to age discrimination that forces qualified elderly workers out of the workforce. While lower physical capabilities and higher wage costs for experienced professionals among elderly workers may contribute to their unemployment, the prevailing beliefs about aging leading to declining health and challenges in adapting to job changes also exert significant influence on the unemployment of elderly workers, regardless of the actual qualifications of workers.

13,14,15

Women demonstrated a stronger correlation between older age and health-related unemployment, consistent with previous studies.

16,17 For women, maintaining a youthful appearance is beneficial for staying competitive in the job market. Conversely, in men, an aged appearance may indicate experience and authoritative competence, thereby enhancing their competitiveness in the workplace. However, further research is necessary to validate this relationship.

In addition, the prevalence of health-related unemployment varies according to socioeconomic factors, despite having similar health levels. Our study found that individuals with lower income and education levels were more likely to experience health-related unemployment. This discrepancy is likely influenced by the control exerted by individuals over their jobs in relation to socioeconomic status. Individuals with a higher socioeconomic status often hold positions with lower physical demands and greater occupational autonomy, allowing them to persist in their work even when facing health limitations. In contrast, those with a lower socioeconomic status are more likely to work in positions with health hazards, and to have less control over employment status, thereby increasing vulnerability to involuntary unemployment and job instability. Furthermore, individuals with a higher socioeconomic status tend to have better access to resources and are more likely to retire due to age limits rather than health-related problems. In contrast, those with lower socioeconomic status tend to rely on work for their livelihood and work until health issues compel them to stop.

18,19,20

Receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits showed similar relationships with health-related unemployment as found in previous studies. Brinch

21 indicated that the disability pension program in Norway inadvertently encourages voluntary early labor force withdrawal, leading to resource waste.

Gender differences related to income levels and receipt of the Basic Livelihood Security Program benefits were observed, indicating a higher risk of health-related unemployment among men in comparison to women. This trend may be attributed to the influence of traditional gender roles in East Asia. Due to societal pressure to be the primary earners, men often persist in jobs despite health issues until compelled to stop. This pressure is particularly high for those with a low socioeconomic status who face additional financial hardships and are compelled to keep working despite health challenges, until health conditions worsen and necessitate a halt in employment.

18,19

The strengths of this study can be attributed to the implementation of PSM and KNHANES. Through the application of PSM, confounding effects were successfully mitigated.

10 Selection bias was minimized by use of the KNHANES because the participants were considered representative of the Korean population. Additionally, the KNHANES facilitates the examination of the overall impact of health and socioeconomic factors, providing a direction for further investigation into specific areas.

However, this study has several limitations. First, because the study was cross-sectional, ascertaining the temporal sequence of events was challenging, and establishing a clear cause-and-effect relationship between variables was difficult. Second, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires constituted a potential limitation; however, the participants had little incentive to provide inaccurate information. Third, specific reasons for health-related unemployment were not investigated. The cause of unemployment can vary according to socioeconomic differences, as seen in the significant differences in disability retirement related to musculoskeletal diseases.

22 Fourth, the study’s reliance on a general health survey, which was not specifically tailored to its focus, risks misclassifying participants when redefining the variables. For example, the broad categorization of unemployment reasons, such as “health-related issues” or “unemployment/job-seeking” might confuse those individuals seeking jobs due to health reasons when selecting a category. Fifth, the use of PSM may have reduced the statistical power of the analysis by excluding unmatched samples.

CONCLUSIONS

Older age and low socioeconomic status can increase the risk of health-related unemployment, indicating age discrimination and socioeconomic inequality. Based on these findings, mitigating age discrimination and socioeconomic inequality is essential in addressing unemployment among qualified elderly workers. Further research is necessary to comprehend the underlying mechanisms governing these connections and to identify effective interventions for health-related unemployment. More detailed studies focusing on specific study groups and variables are warranted. For instance, studies should distinguish between involuntary and voluntary health-related unemployment, considering that individuals with low socioeconomic status have limited control over work continuation. Moreover, a longitudinal study is crucial for investigating causal factors over time, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the elements involved.

Acknowledgements

We thank the team of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) and Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) for providing the original KNHANES data. The authors are solely responsible for the contents of the present study, and they do not necessarily represent the official views of the KDCA.

Abbreviations

estimated glomerular filtration rate

EuroQOL five dimension questionnaire

Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

propensity score matching

NOTES

-

Funding: This research is supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022R1F1A1066498).

-

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Authors contributions:

Conceptualization: Kang MY.

Formal analysis: Lee YS.

Supervision: Kang MY.

Validation: Kang MY.

Visualization: Lee YS.

Writing - original draft: Lee YS.

Writing - review & editing: Lee DW, Kang MY.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Table 4

Logistic regression results after restricting age under 65 years old

aoem-36-e16-s004.xls

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

- 1. Owen K, Watson N. Unemployment and mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 1995;2(2):63–71. 7655912.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Acevedo P, Mora-Urda AI, Montero P. Social inequalities in health: duration of unemployment unevenly effects on the health of men and women. Eur J Public Health 2020;30(2):305–310. 31625557.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 3. Stauder J. Unemployment, unemployment duration, and health: selection or causation? Eur J Health Econ 2019;20(1):59–73. 29725787.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 4. Krug G, Eberl A. What explains the negative effect of unemployment on health? An analysis accounting for reverse causality. Res Soc Stratification Mobility 2018;55:25–39.Article

- 5. Schuring M, Robroek SJ, Otten FW, Arts CH, Burdorf A. The effect of ill health and socioeconomic status on labor force exit and re-employment: a prospective study with ten years follow-up in the Netherlands. Scand J Work Environ Health 2013;39(2):134–143. 22961587.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Leinonen T, Martikainen P, Lahelma E. Interrelationships between education, occupational social class, and income as determinants of disability retirement. Scand J Public Health 2012;40(2):157–166. 22312029.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. Arrow JO. Estimating the influence of health as a risk factor on unemployment: a survival analysis of employment durations for workers surveyed in the German Socio-Economic Panel (1984-1990). Soc Sci Med 1996;42(12):1651–1659. 8783427.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Voss P, Wolff JK, Rothermund K. Relations between views on ageing and perceived age discrimination: a domain-specific perspective. Eur J Ageing 2016;14(1):5–15. 28804390.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 9. Hammer GP, du Prel JB, Blettner M. Avoiding bias in observational studies: part 8 in a series of articles on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2009;106(41):664–668. 19946431.PubMedPMC

- 10. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70(1):41–55.Article

- 11. Oh K, Kim Y, Kweon S, Kim S, Yun S, Park S, et al. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 20th anniversary: accomplishments and future directions. Epidemiol Health 2021;43:e2021025. 33872484.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Matthews S, Manor O, Power C. Social inequalities in health: are there gender differences? Soc Sci Med 1999;48(1):49–60. 10048837.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Wood G, Wilkinson A, Harcourt M. Age discrimination and working life: perspectives and contestations–a review of the contemporary literature. Int J Manag Rev 2008;10(4):425–442.Article

- 14. Berger ED. Managing age discrimination: an examination of the techniques used when seeking employment. Gerontologist 2009;49(3):317–332. 19377045.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Vickerstaff S, Van der Horst M. The impact of age stereotypes and age norms on employees’ retirement choices: a neglected aspect of research on extended working lives. Front Sociol 2021;6:686645. 34141736.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Neumark D, Burn I, Button P. Age discrimination and hiring of older workers. FRBSF Econ Lett 2017;06.

- 17. McGann M, Ong R, Bowman D, Duncan A, Kimberley H, Biggs S. Gendered ageism in Australia: changing perceptions of age discrimination among older men and women. Econ Pap 2016;35(4):375–388.ArticlePDF

- 18. Jung J, Choi J, Myong JP, Kim HR, Kang MY. Is educational level linked to unable to work due to ill-health? Saf Health Work 2020;11(2):159–164. 32596010.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Jung J, Lee J, Lee YM, Lee DW, Kim HR, Kang MY. Educational inequalities in ill-health retirement among middle- and older-aged workers in Korea: the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (2006-2016). J Occup Environ Med 2021;63(6):e323–e329. 33950041.PubMed

- 20. Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. J Health Econ 2010;29(1):1–28. 19963292.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Brinch CN. Discussion Papers. The Effect of Benefits on Disability Uptake. Oslo, Norway: Statistics Norway, Research Department; 2009.

- 22. Polvinen A, Laaksonen M, Gould R, Lahelma E, Martikainen P. The contribution of major diagnostic causes to socioeconomic differences in disability retirement. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014;40(4):353–360. 24352164.ArticlePubMed

, Dong-Wook Lee2

, Dong-Wook Lee2 , Mo-Yeol Kang1

, Mo-Yeol Kang1

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite