Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Occup Environ Med > Volume 36; 2024 > Article

- Original Article The risk of insomnia by work schedule instability in Korean firefighters

-

Saebomi Jeong1

, Jeonghun Kim1

, Jeonghun Kim1 , Sung-Soo Oh1

, Sung-Soo Oh1 , Hee-Tae Kang1

, Hee-Tae Kang1 , Yeon-Soon Ahn2,*

, Yeon-Soon Ahn2,* , Kyoung Sook Jeong1,*

, Kyoung Sook Jeong1,*

-

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2024;36:e24.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2024.36.e24

Published online: September 10, 2024

1Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Wonju Severance Christian Hospital, Wonju College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Wonju, Korea

2Department of Preventive Medicine, Wonju College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Wonju, Korea

- *Correspondence: Kyoung Sook Jeong Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Wonju Severance Christian Hospital, Wonju College of Medicine, Yonsei University, 20 Ilsan-ro, Wonju 26426, Korea E-mail: jeongks@yonsei.ac.kr

- *Yeon-Soon Ahn Department of Preventive Medicine, Wonju College of Medicine, Yonsei University, 20 Ilsan-ro, Wonju 26426, Korea E-mail: ysahn1203@gmail.com

© 2024 Korean Society of Occupational & Environmental Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

-

Background Firefighters are exposed to shift work, as well as unpredictable emergency calls and traumatic events, which can lead to sleep problems. This study aimed to investigate the risk of insomnia by work schedule instability in Korean firefighters.

-

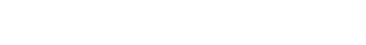

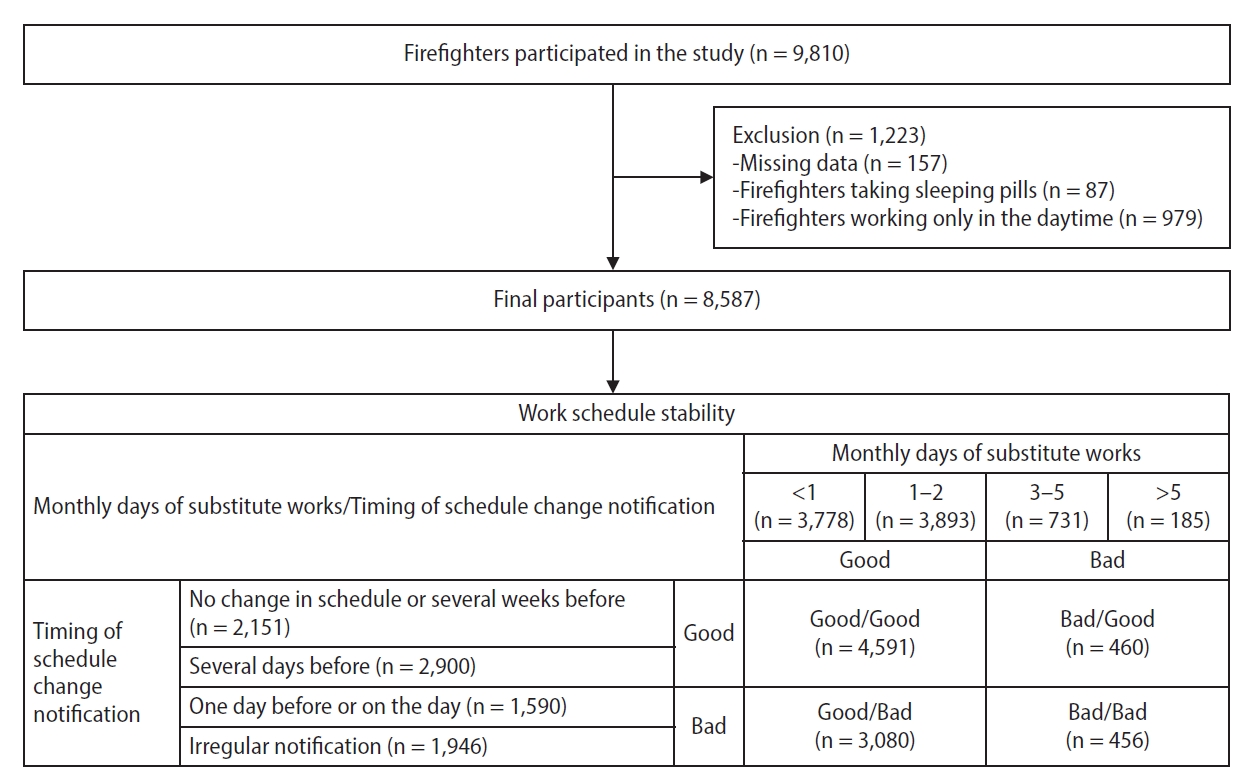

Methods This study used the Insomnia Severity Index to assess the insomnia in firefighters. The work schedule stability was classified with the frequency of the substitute work and the timing of notification for work schedule changes. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the adjusted odds ratio of insomnia by work schedule stability with covariates including sex, age, education, smoking, alcohol, caffeine intake, shift type, job, and underlying conditions.

-

Results Of the 8,587 individuals, 751 (8.75%) had moderate to severe insomnia (Insomnia Severity Index ≥ 15). The prevalence of insomnia was statistically significantly higher as the frequency of substitute work increased: <1 time per month (6.8%), 1–2 times (9.5%), 3–5 times (13.4%), and more than 5 times (15.7%) (p < 0.001). Additionally, the prevalence of insomnia was statistically significantly higher when the timing of the schedule change notification was urgent or irregular: no change or several weeks before (5.4%), several days before (7.9%), one day before or on the day (11.2%), irregularly notification (11.6%) (p < 0.001). In comparison to the group with good frequency of the substitute work/good timing of schedule change notification group, the adjusted odds ratios of insomnia were 1.480 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.237–1.771) for Good/Bad group, 1.862 (95% CI: 1.340–2.588) for Bad/Good group, and 1.885 (95% CI: 1.366–2.602) for Bad/Bad group.

-

Conclusions Work schedule instability was important risk factor of insomnia in firefighters. It suggests that improving the stability of work schedules could be a key strategy for reducing sleep problems in this occupational group.

BACKGROUND

METHODS

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

Abbreviations

BMI

CI

EMS

GAD-7

HPA

ISI

OR

PC-PTSD

PHQ-9

PTSD

-

Competing interests

Sung-Soo Oh, Yeon-Soon Ahn, and Kyoung Sook Jeong contributing editors of the Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, were not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Ahn YS, Jeong KS. Data curation: Jeong S, Kim J. Formal analysis: Ahn YS, Jeong S. Investigation: Ahn YS, Jeong KS. Methodology: Jeong S, Oh SS. Software: Jeong KS. Supervision: Kang HT, Oh SS. Validation: Jeong KS, Ahn YS. Visualization: Jeong S. Writing - original draft: Jeong S. Writing - review & editing: Jeong KS, Ahn YS.

-

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Emergency Response to Disaster sites Research and Development Program funded by Korean National Fire Agency (20013968, Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology, KEIT).

NOTES

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary Table 2.

| Variable | Total (n = 8,587) |

Insomniaa |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 7,836, 91.25%) | Yes (n = 751, 8.75%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 8,056 (93.8) | 7,366 (91.4) | 690 (8.6) | 0.021 |

| Female | 531 (6.2) | 470 (88.5) | 61 (11.5) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 20–29 | 1,241 (14.5) | 1,160 (93.5) | 81 (6.5) | 0.003 |

| 30–39 | 3,571 (41.6) | 3,265 (91.4) | 306 (8.6) | |

| 40–49 | 2,497 (29.1) | 2,269 (90.9) | 228 (9.1) | |

| ≥50 | 1,278 (14.9) | 1,142 (89.4) | 136 (10.6) | |

| Mean ± SD | 39.13 ± 8.50 | 39.03 ± 8.50 | 40.25 ± 8.40 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| <25 | 5,482 (63.8) | 4,995 (91.1) | 487 (8.9) | 0.548 |

| ≥25 | 3,105 (36.2) | 2,841 (91.5) | 264 (8.5) | |

| Mean ± SD | 24.27 ± 2.51 | 24.27 ± 2.50 | 24.23 ± 2.67 | 0.631 |

| Education | ||||

| High school | 1,873 (21.8) | 1,716 (91.6) | 157 (8.4) | 0.184 |

| College | 2,720 (31.7) | 2,499 (91.9) | 221 (8.1) | |

| ≥University | 3,994 (46.5) | 3,621 (90.7) | 373 (9.3) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 2,691 (31.3) | 2,494 (92.7) | 197 (7.3) | 0.002 |

| Married | 5,896 (68.7) | 5,342 (90.6) | 554 (9.4) | |

| Monthly income (×1,000 KRW) | ||||

| 2,000–2,999 | 3,127 (36.4) | 2,895 (92.6) | 232 (7.4) | 0.003 |

| 3,000–4,999 | 4,195 (48.9) | 3,805 (90.7) | 390 (9.3) | |

| ≥5,000 | 1,265 (14.7) | 1,136 (89.8) | 129 (10.2) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker | 3,218 (37.5) | 2,918 (90.7) | 300 (9.3) | 0.047 |

| Ex-smoker | 2,934 (34.2) | 2,667 (90.9) | 267 (9.1) | |

| Current smoker | 2,435 (28.4) | 2,251 (92.4) | 184 (7.6) | |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| No | 2,356 (27.4) | 2,127 (90.3) | 229 (9.7) | 0.049 |

| Yes | 6,231 (72.6) | 5,709 (91.6) | 522 (8.4) | |

| Caffeine intake | ||||

| No | 1,374 (16.0) | 1,227 (89.3) | 147 (10.7) | 0.005 |

| Yes | 7,213 (84.0) | 6,609 (91.6) | 604 (8.4) | |

| Exercise | ||||

| No | 2,741 (31.9) | 2,468 (90.0) | 273 (10.0) | 0.006 |

| Yes | 5,846 (68.1) | 5,368 (91.8) | 478 (8.2) | |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard error.

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; KRW: Korean Won; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index.

aInsomnia was classified with No or Yes by ISI score (No: <15; Yes: ≥15);

bCalculated by chi-square test for binomial variables and t-test for numeric variables.

| Variable | Total (n = 8,587) |

Insomniaa |

p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 7,836, 91.25%) | Yes (n = 751, 8.75%) | |||

| Hypertension | ||||

| Yes | 779 (9.1) | 661 (84.9) | 118 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,808 (90.9) | 7,175 (91.9) | 633 (8.1) | |

| Dyslipidemia | ||||

| Yes | 751 (8.7) | 987 (86.7) | 151 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,836 (91.3) | 6,849 (91.9) | 600 (8.1) | |

| Cardiac disease | ||||

| Yes | 177 (2.1) | 138 (78.0) | 39 (22.0) | <0.001 |

| No | 8,410 (97.9) | 7,398 (91.5) | 712 (8.5) | |

| Skin disease | ||||

| Yes | 949 (11.1) | 787 (82.9) | 162 (17.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,638 (88.9) | 7,049 (92.3) | 589 (7.7) | |

| Depressive symptomc | ||||

| Yes | 1,454 (16.9) | 982 (67.5) | 472 (32.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,133 (83.1) | 6,854 (96.1) | 279 (3.1) | |

| Anxiety symptomd | ||||

| Yes | 981 (11.4) | 614 (62.6) | 367 (37.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,606 (88.6) | 7,222 (95.0) | 384 (5.0) | |

| PTSD symptome | ||||

| Yes | 826 (9.6) | 558 (67.6) | 268 (32.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,761 (90.4) | 7,278 (93.8) | 483 (6.2) | |

Values are presented as number (%).

PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; PC-PTSD: Primary Care-PTSD screen.

aInsomnia was classified with No or Yes by ISI score (No: <15, Yes: ≥15);

bCalculated by chi-square test;

cDepressive symptom was classified with No or Yes by PHQ-9 score (No: <5, Yes: ≥5);

dAnxiety symptom was classified with No or Yes by GAD-7 score (No: <5, Yes: ≥5);

ePTSD symptom was classified with No or Yes by PC-PTSD (No: <3, Yes: ≥3 items).

| Variable | Total (n = 8,587) |

Insomniaa |

p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 7,836, 91.25%) | Yes (n = 751, 8.75%) | |||

| Type of shift | ||||

| 3-Day cycle | 667 (7.8) | 618 (92.7) | 49 (7.3) | 0.552 |

| 6-Day cycle | 156 (1.8) | 140 (89.7) | 16 (10.3) | |

| 9-Day cycle | 1,169 (13.6) | 1,058 (90.5) | 111 (9.5) | |

| 21-Day cycle | 6,215 (72.4) | 5,675 (91.3) | 540 (8.7) | |

| Others | 380 (4.4) | 345 (90.8) | 35 (9.2) | |

| Job | ||||

| Administration | 96 (1.1) | 89 (92.7) | 7 (7.3) | 0.014 |

| Fire suppression | 2,956 (34.4) | 2,684 (90.8) | 272 (9.2) | |

| EMS | 2,496 (29.1) | 2,258 (90.5) | 238 (9.5) | |

| Rescue | 952 (11.1) | 897 (94.2) | 55 (5.8) | |

| Fire investigation | 220 (2.6) | 198 (90.0) | 22 (10.0) | |

| Others | 1,867 (21.7) | 1,710 (91.6) | 157 (8.4) | |

| Monthly number of substitute workc | ||||

| <1 | 3,778 (44.0) | 3,522 (93.2) | 256 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| 1–2 | 3,893 (45.3) | 3,525 (90.2) | 368 (9.5) | |

| 3–5 | 731 (8.5) | 633 (86.6) | 98 (13.4) | |

| >5 | 185 (2.2) | 156 (84.3) | 29 (15.7) | |

| Timing of schedule change notificationd | ||||

| No change or several weeks before | 2,151 (25.0) | 2,034 (94.6) | 117 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Several days before | 2,900 (33.8) | 2,670 (92.1) | 230 (7.9) | |

| One day before or on the day | 1,590 (18.5) | 1,412 (88.8) | 178 (11.2) | |

| Irregularly notification | 1,946 (22.7) | 1,720 (88.4) | 226 (11.6) | |

| Work schedule stabilitye | ||||

| Good/Good | 4,591 (53.5) | 4,304 (93.7) | 287 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Good/Bad | 3,080 (35.9) | 2,743 (89.1) | 337 (10.9) | |

| Bad/Good | 460 (5.4) | 400 (87.0) | 60 (13.0) | |

| Bad/Bad | 456 (5.3) | 389 (85.3) | 67 (14.7) |

Values are presented as number (%).

EMS: emergency medical services; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index.

aInsomnia was classified with No or Yes by ISI score (No: <15, Yes: ≥15);

bCalculated by chi-square test;

cMonthly number of substitute works was classified with Good or Bad (Good: monthly number <3; Bad: monthly number ≥3);

dTiming of schedule change notification was classified with Good or Bad (Good: no change or notification several weeks before or several days before; Bad: notification one day before or on the day or irregular notification);

eWork schedule stability was classified by monthly number of substitute work and timing of schedule change notification.

| Crude | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly number of substitute workd | ||||

| <1 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| 1–2 | 1.436 (1.216–1.696) | 1.375 (1.064–1.778) | 1.298 (1.083–1.556) | 1.327 (1.103–1.597) |

| 3–5 | 2.130 (1.663–2.729) | 2.234 (1.741–2.867) | 1.738 (1.320–2.289) | 1.794 (1.355–2.375) |

| >5 | 2.558 (1.687–3.878) | 2.694 (1.773–4.092) | 1.783 (1.121–2.835) | 1.823 (1.142–2.910) |

| Timing of schedule change notificatione | ||||

| No change or several weeks before | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Several days before | 1.498 (1.190–1.885) | 1.517 (1.205–1.910) | 1.449 (1.132–1.854) | 1.448 (1.130–1.855) |

| One day before or on the day | 2.192 (1.719–2.794) | 2.130 (1.669–2.717) | 1.729 (1.329–2.249) | 1.719 (1.320–2.238) |

| Irregular notification | 2.284 (1.811–2.882) | 2.285 (1.810–2.885) | 1.810 (1.407–2.327) | 1.816 (1.410–2.338) |

| Work schedule stabilityf | ||||

| Good/Good | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Good/Bad | 1.842 (1.563–2.172) | 1.801 (1.527–2.125) | 1.475 (1.233–1.763) | 1.480 (1.237–1.771) |

| Bad/Good | 2.249 (1.672–3.026) | 2.314 (1.719–3.115) | 1.789 (1.290–2.481) | 1.862 (1.340–2.588) |

| Bad/Bad | 2.583 (1.942–3.436) | 2.609 (1.959–3.473) | 1.851 (1.347–2.544) | 1.885 (1.366–2.602) |

The adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) was calculated via binomial logistic regression analyses.

aModel 1: adjusted for sex and age;

bModel 2: adjusted for all variables in Model 1, body mass index, education, smoking status, alcohol consumption, caffeine intake, exercise, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiac disease, skin disease, and depressive symptom;

cModel 3: adjusted for all variables in model 2, shift type, and job;

dMonthly number of substitute work was classified with Good or Bad (Good: monthly number <3; Bad: monthly number ≥3);

eTiming of schedule change notification was classified with Good or Bad (Good: no change or notification several weeks before or several days before; Bad: notification one day before or on the day or irregular notification);

fWork schedule stability was classified by monthly number of substitute work and timing of schedule change notification.

- 1. Killgore WD. Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Prog Brain Res 2010;185:105–29.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Buxton OM, Marcelli E. Short and long sleep are positively associated with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease among adults in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2010;71(5):1027–36.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Kahn-Greene ET, Killgore DB, Kamimori GH, Balkin TJ, Killgore WD. The effects of sleep deprivation on symptoms of psychopathology in healthy adults. Sleep Med 2007;8(3):215–21.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Demers PA, DeMarini DM, Fent KW, Glass DC, Hansen J, Adetona O, et al. Carcinogenicity of occupational exposure as a firefighter. Lancet Oncol 2022;23(8):985–6.ArticlePubMed

- 5. IARC Monographs Vol 124 Group. Carcinogenicity of night shift work. Lancet Oncol 2019;20(8):1058–9.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Barger LK, Rajaratnam SM, Wang W, O'Brien CS, Sullivan JP, Qadri S, et al. Common sleep disorders increase risk of motor vehicle crashes and adverse health outcomes in firefighters. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11(3):233–40.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Uehli K, Mehta AJ, Miedinger D, Hug K, Schindler C, Holsboer-Trachsler E, et al. Sleep problems and work injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2014;18(1):61–73.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Suh S, Cho N, Zhang J. Sex differences in insomnia: from epidemiology and etiology to intervention. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2018;20(9):69.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Ancoli-Israel S, Cooke JR. Prevalence and comorbidity of insomnia and effect on functioning in elderly populations. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(7 Suppl):S264–71.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Cai GH, Theorell-Haglow J, Janson C, Svartengren M, Elmstahl S, Lind L, et al. Insomnia symptoms and sleep duration and their combined effects in relation to associations with obesity and central obesity. Sleep Med 2018;46:81–7.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Gellis LA, Lichstein KL, Scarinci IC, Durrence HH, Taylor DJ, Bush AJ, et al. Socioeconomic status and insomnia. J Abnorm Psychol 2005;114(1):111–8.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Shochat T. Impact of lifestyle and technology developments on sleep. Nat Sci Sleep 2012;4:19–31.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Phillips B, Mannino DM. Do insomnia complaints cause hypertension or cardiovascular disease? J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3(5):489–94.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Joo JH, Lee DW, Choi DW, Park EC. Association between night work and dyslipidemia in South Korean men and women: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis 2019;18(1):75.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 15. Kaaz K, Szepietowski JC, Matusiak L. Influence of itch and pain on sleep quality in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol 2019;99(2):175–80.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep 2013;36(7):1059–68.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Lamarche LJ, De Koninck J. Sleep disturbance in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68(8):1257–70.ArticlePubMed

- 18. 2023 National Fire Agency Statistical Yearbook of Republic of Korea. https://www.nfa.go.kr/nfa/. Updated 2023. Accessed July 31, 2023

- 19. Harvey SB, Milligan-Saville JS, Paterson HM, Harkness EL, Marsh AM, Dobson M, et al. The mental health of fire-fighters: An examination of the impact of repeated trauma exposure. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2016;50(7):649–58.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 20. Jang TW, Jeong KS, Ahn YS, Choi KS. The relationship between the pattern of shift work and sleep disturbances in Korean firefighters. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2020;93(3):391–8.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 21. Garbarino S, Guglielmi O, Puntoni M, Bragazzi NL, Magnavita N. Sleep quality among police officers: implications and insights from a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16(5):885.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Good CH, Brager AJ, Capaldi VF, Mysliwiec V. Sleep in the United States military. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020;45(1):176–91.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 23. McDowall K, Murphy E, Anderson K. The impact of shift work on sleep quality among nurses. Occup Med (Lond) 2017;67(8):621–5.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Khoshakhlagh AH, Al Sulaie S, Yazdanirad S, Orr RM, Dehdarirad H, Milajerdi A. Global prevalence and associated factors of sleep disorders and poor sleep quality among firefighters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2023;9(2):e13250.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Chin DL, Odes R, Hong O. Job stress and sleep disturbances among career firefighters in northern California. J Occup Environ Med 2023;65(8):706–10.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Lim DK, Baek KO, Chung IS, Lee MY. Factors related to sleep disorders among male firefighters. Ann Occup Environ Med 2014;26:11.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 27. Thorndike FP, Ritterband LM, Saylor DK, Magee JC, Gonder-Frederick LA, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index as a web-based measure. Behav Sleep Med 2011;9(4):216–23.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Schneider D, Harknett K. Consequences of routine work-schedule instability for worker health and well-being. Am Sociol Rev 2019;84(1):82–114.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 29. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606–13.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Williams N. The GAD-7 questionnaire. Occup Med 2014;64(3):224.Article

- 31. Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Cameron RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatry 2003;9(1):9–14.Article

- 32. Oh HJ, Sim CS, Jang TW, Ahn YS, Jeong KS. Association between sleep quality and type of shift work in Korean firefighters. Ann Occup Environ Med 2022;34:e27.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 33. Lim M, Lee S, Seo K, Oh HJ, Shin JS, Kim SK, et al. Psychosocial factors affecting sleep quality of pre-employed firefighters: a cross-sectional study. Ann Occup Environ Med 2020;32:e12.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 34. Choi SM, Kim CW, Park HO, Park YT. Association between unpredictable work schedule and work-family conflict in Korea. Ann Occup Environ Med 2023;35:e46.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 35. Hurley BF. Age, gender, and muscular strength. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50 Spec No:41–4.PubMed

- 36. Costa G, Sartori S, Akerstedt T. Influence of flexibility and variability of working hours on health and well-being. Chronobiol Int 2006;23(6):1125–37.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Geiger-Brown J, Trinkoff A, Rogers VE. The impact of work schedules, home, and work demands on self-reported sleep in registered nurses. J Occup Environ Med 2011;53(3):303–7.ArticlePubMed

- 38. Akerstedt T, Kecklund G. What work schedule characteristics constitute a problem to the individual? A representative study of Swedish shift workers. Appl Ergon 2017;59(Pt A):320–5.ArticlePubMed

- 39. Boivin DB, Boudreau P. Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2014;62(5):292–301.ArticlePubMed

- 40. Meerlo P, Sgoifo A, Suchecki D. Restricted and disrupted sleep: effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep Med Rev 2008;12(3):197–210.ArticlePubMed

- 41. Minkel J, Moreta M, Muto J, Htaik O, Jones C, Basner M, et al. Sleep deprivation potentiates HPA axis stress reactivity in healthy adults. Health Psychol 2014;33(11):1430–4.ArticlePubMed

- 42. Billings J, Focht W. Firefighter shift schedules affect sleep quality. J Occup Environ Med 2016;58(3):294–8.ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- Mapping Connection and Direction Among Symptoms of Sleep Disturbance and Perceived Stress in Firefighters: Embracing the Network Analysis Perspective

Bin Liu, Mingxuan Zou, Lin Liu, Zhongying Wu, Yinchuan Jin, Yuting Feng, Qiannan Jia, Mengze Li, Lei Ren, Qun Yang

Nature and Science of Sleep.2025; Volume 17: 1143. CrossRef - Environmental noise exposure and a new biomarker of Alzheimer's disease: A pilot study

Jonghun Lee, Cheol-Woon Kim, Youjin Kim, Seunghyun Lee, Joon Yul Choi, Wanhyung Lee

Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.2025;[Epub] CrossRef

Fig. 1.

| Variable | Total (n = 8,587) | Insomnia |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 7,836, 91.25%) | Yes (n = 751, 8.75%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 8,056 (93.8) | 7,366 (91.4) | 690 (8.6) | 0.021 |

| Female | 531 (6.2) | 470 (88.5) | 61 (11.5) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 20–29 | 1,241 (14.5) | 1,160 (93.5) | 81 (6.5) | 0.003 |

| 30–39 | 3,571 (41.6) | 3,265 (91.4) | 306 (8.6) | |

| 40–49 | 2,497 (29.1) | 2,269 (90.9) | 228 (9.1) | |

| ≥50 | 1,278 (14.9) | 1,142 (89.4) | 136 (10.6) | |

| Mean ± SD | 39.13 ± 8.50 | 39.03 ± 8.50 | 40.25 ± 8.40 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| <25 | 5,482 (63.8) | 4,995 (91.1) | 487 (8.9) | 0.548 |

| ≥25 | 3,105 (36.2) | 2,841 (91.5) | 264 (8.5) | |

| Mean ± SD | 24.27 ± 2.51 | 24.27 ± 2.50 | 24.23 ± 2.67 | 0.631 |

| Education | ||||

| High school | 1,873 (21.8) | 1,716 (91.6) | 157 (8.4) | 0.184 |

| College | 2,720 (31.7) | 2,499 (91.9) | 221 (8.1) | |

| ≥University | 3,994 (46.5) | 3,621 (90.7) | 373 (9.3) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 2,691 (31.3) | 2,494 (92.7) | 197 (7.3) | 0.002 |

| Married | 5,896 (68.7) | 5,342 (90.6) | 554 (9.4) | |

| Monthly income (×1,000 KRW) | ||||

| 2,000–2,999 | 3,127 (36.4) | 2,895 (92.6) | 232 (7.4) | 0.003 |

| 3,000–4,999 | 4,195 (48.9) | 3,805 (90.7) | 390 (9.3) | |

| ≥5,000 | 1,265 (14.7) | 1,136 (89.8) | 129 (10.2) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker | 3,218 (37.5) | 2,918 (90.7) | 300 (9.3) | 0.047 |

| Ex-smoker | 2,934 (34.2) | 2,667 (90.9) | 267 (9.1) | |

| Current smoker | 2,435 (28.4) | 2,251 (92.4) | 184 (7.6) | |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| No | 2,356 (27.4) | 2,127 (90.3) | 229 (9.7) | 0.049 |

| Yes | 6,231 (72.6) | 5,709 (91.6) | 522 (8.4) | |

| Caffeine intake | ||||

| No | 1,374 (16.0) | 1,227 (89.3) | 147 (10.7) | 0.005 |

| Yes | 7,213 (84.0) | 6,609 (91.6) | 604 (8.4) | |

| Exercise | ||||

| No | 2,741 (31.9) | 2,468 (90.0) | 273 (10.0) | 0.006 |

| Yes | 5,846 (68.1) | 5,368 (91.8) | 478 (8.2) | |

| Variable | Total (n = 8,587) | Insomnia |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 7,836, 91.25%) | Yes (n = 751, 8.75%) | |||

| Hypertension | ||||

| Yes | 779 (9.1) | 661 (84.9) | 118 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,808 (90.9) | 7,175 (91.9) | 633 (8.1) | |

| Dyslipidemia | ||||

| Yes | 751 (8.7) | 987 (86.7) | 151 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,836 (91.3) | 6,849 (91.9) | 600 (8.1) | |

| Cardiac disease | ||||

| Yes | 177 (2.1) | 138 (78.0) | 39 (22.0) | <0.001 |

| No | 8,410 (97.9) | 7,398 (91.5) | 712 (8.5) | |

| Skin disease | ||||

| Yes | 949 (11.1) | 787 (82.9) | 162 (17.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,638 (88.9) | 7,049 (92.3) | 589 (7.7) | |

| Depressive symptom |

||||

| Yes | 1,454 (16.9) | 982 (67.5) | 472 (32.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,133 (83.1) | 6,854 (96.1) | 279 (3.1) | |

| Anxiety symptom |

||||

| Yes | 981 (11.4) | 614 (62.6) | 367 (37.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,606 (88.6) | 7,222 (95.0) | 384 (5.0) | |

| PTSD symptom |

||||

| Yes | 826 (9.6) | 558 (67.6) | 268 (32.4) | <0.001 |

| No | 7,761 (90.4) | 7,278 (93.8) | 483 (6.2) | |

| Variable | Total (n = 8,587) | Insomnia |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 7,836, 91.25%) | Yes (n = 751, 8.75%) | |||

| Type of shift | ||||

| 3-Day cycle | 667 (7.8) | 618 (92.7) | 49 (7.3) | 0.552 |

| 6-Day cycle | 156 (1.8) | 140 (89.7) | 16 (10.3) | |

| 9-Day cycle | 1,169 (13.6) | 1,058 (90.5) | 111 (9.5) | |

| 21-Day cycle | 6,215 (72.4) | 5,675 (91.3) | 540 (8.7) | |

| Others | 380 (4.4) | 345 (90.8) | 35 (9.2) | |

| Job | ||||

| Administration | 96 (1.1) | 89 (92.7) | 7 (7.3) | 0.014 |

| Fire suppression | 2,956 (34.4) | 2,684 (90.8) | 272 (9.2) | |

| EMS | 2,496 (29.1) | 2,258 (90.5) | 238 (9.5) | |

| Rescue | 952 (11.1) | 897 (94.2) | 55 (5.8) | |

| Fire investigation | 220 (2.6) | 198 (90.0) | 22 (10.0) | |

| Others | 1,867 (21.7) | 1,710 (91.6) | 157 (8.4) | |

| Monthly number of substitute work |

||||

| <1 | 3,778 (44.0) | 3,522 (93.2) | 256 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| 1–2 | 3,893 (45.3) | 3,525 (90.2) | 368 (9.5) | |

| 3–5 | 731 (8.5) | 633 (86.6) | 98 (13.4) | |

| >5 | 185 (2.2) | 156 (84.3) | 29 (15.7) | |

| Timing of schedule change notification |

||||

| No change or several weeks before | 2,151 (25.0) | 2,034 (94.6) | 117 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Several days before | 2,900 (33.8) | 2,670 (92.1) | 230 (7.9) | |

| One day before or on the day | 1,590 (18.5) | 1,412 (88.8) | 178 (11.2) | |

| Irregularly notification | 1,946 (22.7) | 1,720 (88.4) | 226 (11.6) | |

| Work schedule stability |

||||

| Good/Good | 4,591 (53.5) | 4,304 (93.7) | 287 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Good/Bad | 3,080 (35.9) | 2,743 (89.1) | 337 (10.9) | |

| Bad/Good | 460 (5.4) | 400 (87.0) | 60 (13.0) | |

| Bad/Bad | 456 (5.3) | 389 (85.3) | 67 (14.7) |

| Crude | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly number of substitute work |

||||

| <1 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| 1–2 | 1.436 (1.216–1.696) | 1.375 (1.064–1.778) | 1.298 (1.083–1.556) | 1.327 (1.103–1.597) |

| 3–5 | 2.130 (1.663–2.729) | 2.234 (1.741–2.867) | 1.738 (1.320–2.289) | 1.794 (1.355–2.375) |

| >5 | 2.558 (1.687–3.878) | 2.694 (1.773–4.092) | 1.783 (1.121–2.835) | 1.823 (1.142–2.910) |

| Timing of schedule change notification |

||||

| No change or several weeks before | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Several days before | 1.498 (1.190–1.885) | 1.517 (1.205–1.910) | 1.449 (1.132–1.854) | 1.448 (1.130–1.855) |

| One day before or on the day | 2.192 (1.719–2.794) | 2.130 (1.669–2.717) | 1.729 (1.329–2.249) | 1.719 (1.320–2.238) |

| Irregular notification | 2.284 (1.811–2.882) | 2.285 (1.810–2.885) | 1.810 (1.407–2.327) | 1.816 (1.410–2.338) |

| Work schedule stability |

||||

| Good/Good | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Good/Bad | 1.842 (1.563–2.172) | 1.801 (1.527–2.125) | 1.475 (1.233–1.763) | 1.480 (1.237–1.771) |

| Bad/Good | 2.249 (1.672–3.026) | 2.314 (1.719–3.115) | 1.789 (1.290–2.481) | 1.862 (1.340–2.588) |

| Bad/Bad | 2.583 (1.942–3.436) | 2.609 (1.959–3.473) | 1.851 (1.347–2.544) | 1.885 (1.366–2.602) |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard error. SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; KRW: Korean Won; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index. Insomnia was classified with No or Yes by ISI score (No: <15; Yes: ≥15); Calculated by chi-square test for binomial variables and t-test for numeric variables.

Values are presented as number (%). PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; PC-PTSD: Primary Care-PTSD screen. Insomnia was classified with No or Yes by ISI score (No: <15, Yes: ≥15); Calculated by chi-square test; Depressive symptom was classified with No or Yes by PHQ-9 score (No: <5, Yes: ≥5); Anxiety symptom was classified with No or Yes by GAD-7 score (No: <5, Yes: ≥5); PTSD symptom was classified with No or Yes by PC-PTSD (No: <3, Yes: ≥3 items).

Values are presented as number (%). EMS: emergency medical services; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index. Insomnia was classified with No or Yes by ISI score (No: <15, Yes: ≥15); Calculated by chi-square test; Monthly number of substitute works was classified with Good or Bad (Good: monthly number <3; Bad: monthly number ≥3); Timing of schedule change notification was classified with Good or Bad (Good: no change or notification several weeks before or several days before; Bad: notification one day before or on the day or irregular notification); Work schedule stability was classified by monthly number of substitute work and timing of schedule change notification.

The adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) was calculated via binomial logistic regression analyses. Model 1: adjusted for sex and age; Model 2: adjusted for all variables in Model 1, body mass index, education, smoking status, alcohol consumption, caffeine intake, exercise, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiac disease, skin disease, and depressive symptom; Model 3: adjusted for all variables in model 2, shift type, and job; Monthly number of substitute work was classified with Good or Bad (Good: monthly number <3; Bad: monthly number ≥3); Timing of schedule change notification was classified with Good or Bad (Good: no change or notification several weeks before or several days before; Bad: notification one day before or on the day or irregular notification); Work schedule stability was classified by monthly number of substitute work and timing of schedule change notification.

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite