Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Occup Environ Med > Volume 35; 2023 > Article

-

[Special Collection] Working hours as a social determinants of workers' health

Brief Communication Working hours and the regulations in Korea -

Inah Kim1

, Jeehee Min2

, Jeehee Min2

-

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2023;35:e18.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2023.35.e18

Published online: July 6, 2023

1Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

2Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Hanyang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- Correspondence: Inah Kim. Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Hanyang University College of Medicine, 222 Wangsimni-ro, Seongdong-gu, Seoul, 04763, Korea. inahkim@hanyang.ac.kr

Copyright © 2023 Korean Society of Occupational & Environmental Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

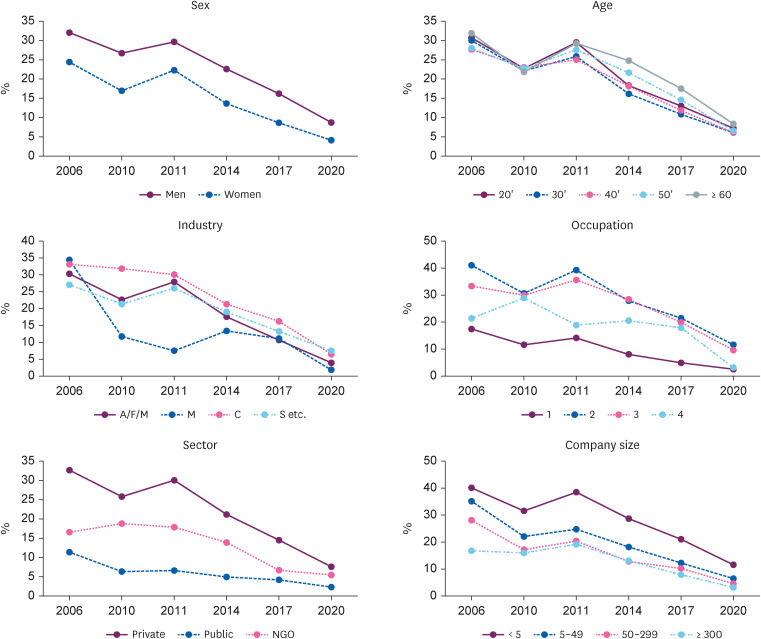

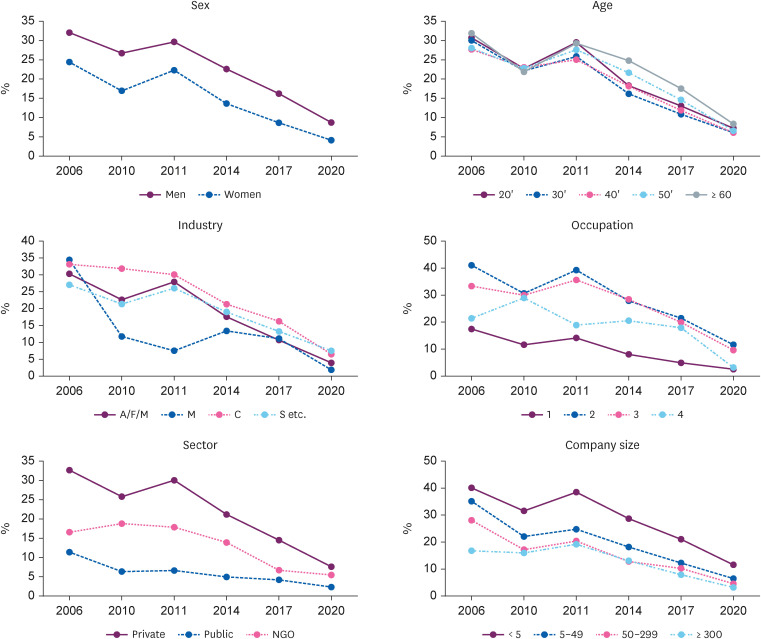

- South Korea has the highest policy priority for working hour regulations because it has longer annual working hours than other Organization for Economic Development Co-operation and Development countries and has fewer holidays. According to the results of the Working Conditions Surveys between 2006 and 2020, in 2020, 6% of wage earners worked for > 52 hours weekly. The percentage of workers exceeding 52 hours weekly has decreased over time; however, disparities exist based on age, industry, occupation, company type, and company size, particularly in service-, arts-, and culture-related occupations and workplaces with fewer than 5 employees. South Korea’s working hours system is greatly influenced by the 52-hour weekly maximum; sometimes, a maximum of 64–69 hours, including overtime, is theoretically possible. To ensure healthy working hours, it is important to actively protect workers who fall through the cracks, such as those in businesses with fewer than 5 employees.

Abbreviations

COVID-19

ILO

LSA

NGO

OECD

WHO

-

Funding: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (NRF–2021R1A2C1008227).

-

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

NOTES

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

- 1. Descatha A, Sembajwe G, Pega F, Ujita Y, Baer M, Boccuni F, et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int 2020;142:105746. 32505015.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Li J, Pega F, Ujita Y, Brisson C, Clays E, Descatha A, et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int 2020;142:105739. 32505014.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Dembe AE, Erickson JB, Delbos RG, Banks SM. The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: new evidence from the United States. Occup Environ Med 2005;62(9):588–597. 16109814.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Vegso S, Cantley L, Slade M, Taiwo O, Sircar K, Rabinowitz P, et al. Extended work hours and risk of acute occupational injury: a case-crossover study of workers in manufacturing. Am J Ind Med 2007;50(8):597–603. 17594716.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Messenger JC. Working Time and Workers’ Preferences in Industrialized Countries: Finding the Balance. 1st ed. London, UK and New York, NY, USA: Routledge; 2004.

- 6. International Labour Organization. Decent Working Time – Balancing Workers’ Needs with Business Requirements. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2007.

- 7. Kang ST. Amendment of weekly rest systems under the Labor Standards Act. Korean J Law Soc 2017;54:211–239.Article

- 8. Kim I, Koo MJ, Lee HE, Won YL, Song J. Overwork-related disorders and recent improvement of national policy in South Korea. J Occup Health 2019;61(4):288–296. 31025505.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 9. International Labour Organization. Ensuring Decent Working Time for the Future. International Labour Conference, 107th Session, 2018. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2018.

- 10. The Guardian. South Korea U-turns on 69-hour working week after youth backlash: protesters claim proposed increase in hours would risk health and fail to boost low birth rate. Updated 2023]. Accessed April 20, 2023]. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/mar/15/south-korea-u-turns-on-69-hour-working-week-after-youth-backlash .

- 11. Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency. Press release. The result of 6th Working Condition Survey, March 9, 2022. Ulsan, Korea: Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency; 2022.

- 12. International Labour Organization. Working Time and Work-Life Balance Around the World. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office; 2022.

- 13. Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. 2021 Workers’ Vacation Survey. Updated 2022]. Accessed April 22, 2023]. https://www.mcst.go.kr/kor/s_policy/dept/deptView.jsp?pSeq=1852&pDataCD=0406000000 .

- 14. Byeon SJ, Oh S, Jo SH, Kim EJ, Lee H. National Work-Life Balance Survey. Sejong, Korea: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2022.

- 15. Korean Law Information Center. Labor Standard Act. Updated 2021]. Accessed April 22, 2023]. https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=labor+standard&x=34&y=19#EJ53:0 .

- 16. Tucker P, Folkar S. Working Time, Health, and Safety: A Research Synthesis Paper. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2012.

- 17. OECD iLibrary. OECD Employment Outlook 2021: Navigating the COVID-19 Crisis and Recovery. 5. Working time and its regulation in OECD countries: how much do we work and how?. Accessed April 20, 2023]. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/c18a4378-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/c18a4378-en#component-d1e4862415 .

- 18. International Labour Organization. C001 - Hours of work (Industry) convention, 1919 (No. 1). Accessed April 20, 2023]. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C001 .

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

Percentage of wage earners working > 52 hours weekly (%).

Working hours’ regulations in South Korea

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- Associations of combined work schedules and atypical working hours with mental health among South Korean police officers: a cross-sectional study

Jungwon Jang, Joungsue Kim, Youngjin Choi, Jeehee Min, Inah Kim

BMC Public Health.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - Gender differences in the association between long working hours and the onset of depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older workers in Korea: A population-based longitudinal study (2006–2022)

Seong-Uk Baek, Yu-Min Lee, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Maturitas.2025; 193: 108175. CrossRef - Association of precarious employment with depressive symptoms and insomnia: Findings from the Korean Working Conditions Survey

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Journal of Psychiatric Research.2025; 181: 7. CrossRef - Gender differences in the association between long work hours, weekend work, and insomnia symptoms in a nationally representative sample of workers in Korea

Seong-Uk Baek, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Sleep Health.2025; 11(2): 191. CrossRef - Challenges from 14 years of experience at Workers' Health

Centers in basic occupational health services for micro and small enterprises in

Korea: a narrative review

Jeong-Ok Kong, Yeongchull Choi, Seonhee Yang, Kyunghee Jung-Choi

The Ewha Medical Journal.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - The increasing importance of changes in nuptiality: policy mismatch and fertility decline in low-fertility Asian societies

Jolene Tan, Qi Cui, Fumiya Uchikoshi

Chinese Sociological Review.2025; : 1. CrossRef - Association of long working hours with visceral adiposity index, anthropometric indices, and weight management behaviors: a study of Korean workers

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Family Practice.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Gender discrimination in the workplace and the onset of problematic alcohol use among female wage workers: A longitudinal study in Korea

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon, Jong-Uk Won

Social Science & Medicine.2025; 379: 118183. CrossRef - Overwork and changes in brain structure: a pilot study

Wonpil Jang, Sungmin Kim, YouJin Kim, Seunghyun Lee, Joon Yul Choi, Wanhyung Lee

Occupational and Environmental Medicine.2025; 82(3): 105. CrossRef - Association of social jetlag with cigarette smoking, smoking intensity, and quitting intentions among Korean workers

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Journal of Public Health.2025; 47(3): 610. CrossRef - Employment Quality as a Framework to Understand Precarious Employment and Beyond in Cross‐National Contexts: Conceptual, Methodological, and Practical Recommendations

Julie Vanderleyden, Deborah De Moortel

Sociology Compass.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Association Between Weekend Catch-Up Sleep and Obesity Among Working Adults: A Cross-Sectional Nationwide Population-Based Study

Wonseok Jeong, Min Ji Song, Ji Hye Shin, Ji Hyun Kim

Life.2025; 15(10): 1562. CrossRef - Associations of self-rated health, depression, and work ability with employee control over working time

Heejoo Ko, Seong-Sik Cho, Jaesung Choi, Mo-Yeol Kang

Epidemiology and Health.2025; 47: e2025036. CrossRef - ‘Bad jobs’ in South Korea: A wellbeing-based approach

Sangwoo Lee, Francis Green

The Economic and Labour Relations Review.2025; : 1. CrossRef - Associations of long working hours with the use of combustible cigarettes, electronic cigarettes, and heated tobacco products among young adults: a population-based study of South Korea

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Postgraduate Medical Journal.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Work–life balance in remote working: does organizational support matter?

Eun-Jee Kim, Sunyoung Park

Employee Relations: The International Journal.2025; 47(6): 889. CrossRef - Work-related risk factors of sleep apnea: evidence from the Korean work, sleep, and health study

Heejoo Ko, Seong-Sik Cho, Hye-Eun Lee, Jeehee Min, Mo-Yeol Kang

International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health.2025; 98(9-10): 797. CrossRef - The Psychology of Involution: Taxonomy, Sociocultural Predictors, and Psychological Outcomes

Wen Zhang, Yuwei Wang, Xiaotao Liu, Chen Guo, Zhicheng Lin, Mingjie Zhou, Yan Mu

Journal of Happiness Studies.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Effect of long working hours on psychological distress among young workers in different types of occupation

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Preventive Medicine.2024; 179: 107829. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and diet quality and patterns: A latent profile analysis of a nationally representative sample of Korean workers

Seong-Uk Baek, Jong-Uk Won, Yu-Min Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon

Preventive Medicine.2024; 180: 107890. CrossRef - Long Working Hours, Work-life Imbalance, and Poor Mental Health: A Cross-sectional Mediation Analysis Based on the Sixth Korean Working Conditions Survey, 2020–2021

Seong-Uk Baek, Yu-Min Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon, Jong-Uk Won

Journal of Epidemiology.2024; 34(11): 535. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and the onset of problematic alcohol use in young workers: A population-based longitudinal analysis in South Korea

Seong-Uk Baek, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Journal of Affective Disorders.2024; 344: 141. CrossRef - Sex differences in the association between social jetlag and hazardous alcohol consumption in Korean workers: A nationwide cross-sectional study

Seong-Uk Baek, Jong-Uk Won, Yu-Min Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon

Sleep Medicine.2024; 119: 549. CrossRef - Association of low-quality employment with the development of suicidal thought and suicide planning in workers: A longitudinal study in Korea

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon, Yu-Min Lee, Jong-Uk Won

Social Science & Medicine.2024; 358: 117219. CrossRef - Changes in Korea’s working time policy: the need for research on flexible working hours considering socioeconomic inequality

Inah KIM

Industrial Health.2024; 62(2): 77. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and engagement in preventive healthcare services in Korean workers: Findings from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Seong-Uk Baek, Yu-Min Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon

Preventive Medicine.2024; 180: 107849. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease: a nationwide population-based study in Korea

S.-U. Baek, J.-U. Won, Y.-M. Lee, J.-H. Yoon

Public Health.2024; 232: 188. CrossRef - How does working time impact perceived mental disorders? New insights into the U-shaped relationship

Xiaoru Niu, Chao Li, Yuxin Xia

Frontiers in Public Health.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Temporary Employment Is Associated with Poor Dietary Quality in Middle-Aged Workers in Korea: A Nationwide Study Based on the Korean Healthy Eating Index, 2013–2021

Seong-Uk Baek, Myeong-Hun Lim, Yu-Min Lee, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Nutrients.2024; 16(10): 1482. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and the development of suicidal ideation among female workers: An 8-year population-based study using the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women & Family (2012–2020)

Seong-Uk Baek, Yu-Min Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon

Psychiatry Research.2024; 333: 115731. CrossRef - Long working hours and preventive oral health behaviors: a nationwide study in Korea (2007–2021)

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon, Yu-Min Lee, Jong-Uk Won

Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine.2024; 29: 48. CrossRef - Association between precarious employment and emergence of food insecurity in Korean adults: A population-based longitudinal analysis (2008–2022)

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Social Science & Medicine.2024; 362: 117448. CrossRef - Association of Social Jetlag with the Dietary Quality Among Korean Workers: Findings from a Nationwide Survey

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Nutrients.2024; 16(23): 4091. CrossRef - Association between social jetlag and leisure-time physical activity and muscle strengthening exercise in young adults: findings from a nationally representative sample in South Korea

S.-U. Baek, Y.-M. Lee, J.-U. Won, J.-H. Yoon

Public Health.2024; 237: 30. CrossRef - Association between husband's participation in household work and the onset of depressive symptoms in married women: A population-based longitudinal study in South Korea

Seong-Uk Baek, Yu-Min Lee, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Social Science & Medicine.2024; 362: 117416. CrossRef - Long Working Hours and Unhealthy Lifestyles of Workers: A Protocol for a Scoping Review

Seong-Uk Baek, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Merits.2024; 4(4): 431. CrossRef - Work hours and the risk of hypertension: the case of Indonesia

Friska Aulia Dewi Andini, Adiatma Y. M. Siregar

BMC Public Health.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - The Prevalence of Traumatic Dental Injuries Due to Workplace Safety Accidents among Korean Workers by Occupational Group

Ji-Young Son, Jae-Hyung Lim, Dong-Hun Han

Asian Journal of Social Health and Behavior.2024; 7(3): 109. CrossRef - Special Series I: Working hours as a social determinant of workers’ health

Kyunghee Jung-Choi, Tae-Won Jang, Mo-Yeol Kang, Jungwon Kim, Eun-A Kim

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine.2023;[Epub] CrossRef

Fig. 1

| System | Terms | Regulations | Continuous rest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard working hours | ||||

| Statutory | Standard | 40 hours/week. 8 hours/day | Not applicable | |

| High risk job | 34 hours/week, 6 hours/day | Not applicable | ||

| Overtime limits | Standard | 12 hours/week | Not applicable | |

| Company with under 30 employees | 20 hours/week | Not applicable | ||

| Exceptional industry | No limits | 11 hours of rest after workday | ||

| Special overtime limits | Standard | 24 hours/week | 11 hours of rest after workday (an equal number of hours or more than 24 hours off during or after overtime) | |

| During less than two weeks | No limits | |||

| Flexible working hours | ||||

| Flexible work hour | Standard | Averaging 52 hours/week | Not applicable | |

| During less than 2 weeks | 60 hours/week | Not applicable | ||

| During 2 weeks-3 months | 64 hours/week, 12 hours/day | Not applicable | ||

| During 3–6 months | 64 hours/week, 12 hours/day | 11 hours of rest after workday | ||

| Selective work hour | During less than 1 month | Averaging 52 hours/week | Not applicable | |

| During 1–3 months | Averaging 52 hours/week | 11 hours of rest after workday | ||

Except for workers in companies with fewer than 5 employees.

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite