Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Occup Environ Med > Volume 35; 2023 > Article

-

[Special Collection] Working hours as a social determinants of workers' health

Opinion Statement by the Korean Society of Occupational and Environmental Medicine on the proposed reform of working hours in South Korea -

Hee-Tae Kang1,2

, Chul-Ju Kim1,3

, Chul-Ju Kim1,3 , Dong-Wook Lee1,4

, Dong-Wook Lee1,4 , Seung-Gwon Park1,5

, Seung-Gwon Park1,5 , Jinwoo Lee1,6

, Jinwoo Lee1,6 , Kanwoo Youn1

, Kanwoo Youn1 , Hwan-Cheol Kim1,4

, Hwan-Cheol Kim1,4 , Kyoung Sook Jeong1,2

, Kyoung Sook Jeong1,2 , Hansoo Song1,9

, Hansoo Song1,9 , Sung-Kyung Kim1,8

, Sung-Kyung Kim1,8 , Sang-Baek Koh1,8

, Sang-Baek Koh1,8

-

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2023;35:e17.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.35371/aoem.2023.35.e17

Published online: July 5, 2023

1Institutional Improvement Committee of the Korean Society of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

2Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Wonju Severance Christian Hospital, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

3Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Shincheon Union Hospital, Siheung, Korea.

4Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Inha University Hospital, Inha University, Incheon, Korea.

5Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Cheongju Hankook General Hospital, Cheongju, Korea.

6Center for Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Hanil General Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Wonjin Green Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

8Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

9Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Chosun University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea.

- Correspondence: Sung-Kyung Kim. Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, 222-1 Room, 20 Ilsan-ro, Wonju 26426, Korea. stacte@yonsei.ac.kr

- Correspondence: Sang-Baek Koh. Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, 222-1 Room, 20 Ilsan-ro, Wonju 26426, Korea. kohhj@yonsei.ac.kr

Copyright © 2023 Korean Society of Occupational & Environmental Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

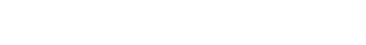

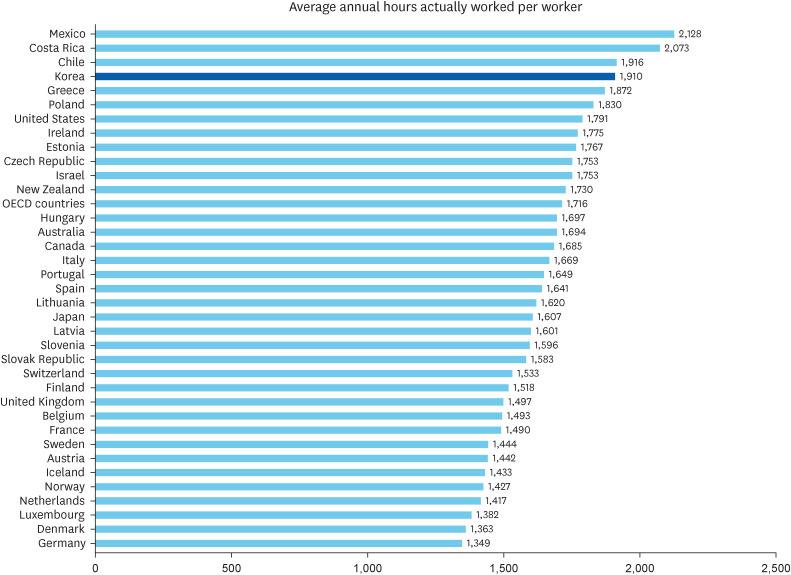

- The current 52-hour workweek in South Korea consists of 40 hours of regular work and 12 hours of overtime. Although the average working hours in South Korea is declining, it is still 199 hours longer than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average of 1,716 hours per year. In view to this, the South Korean government has now proposed to reform the workweek, mainly intending to increase the workweek to 69 hours when the workload is heavy. This reform, by increasing the labor intensity due to long working hours, goes against the global trend of reducing work hours for a safe and healthy working environment. Long working hours can lead to increased cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases, industrial accidents, mental health problems, and safety accidents due to lack of concentration. In conclusion, the Korean government’s working hour reform plan can have a negative impact on workers’ health, and therefore it should be thoroughly reviewed and modified.

Abbreviations

CI

HR

ILO

OECD

OR

RR

WHO

-

Funding: This work was supported by the Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine Research Fund.

-

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Kang HT, Kanwoo Y, Koh SB.

Data curation: Lee DW, Kim HC.

Funding acquisition: Kim SK.

Investigation: Kang HT, Lee DW, Park SG.

Methodology: Jeong KS.

Resources: Kim CJ, Lee J, Jeong KS.

Supervision: Lee DW, Park SG.

Validation: Lee J, Kanwoo Y, Kim HC, Song H, Kim SK.

Visualization: Koh SB.

Writing - original draft: Kang HT, Kim CJ, Koh SB.

Writing - review & editing: Kang HT, Kim SK.

NOTES

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Data 1

- 1. OECD.Stat. Updated 2023]. Accessed May 15, 2023]. https://stats.oecd.org .

- 2. OECD employment outlook 2021. Updated 2021]. Accessed May 15, 2023]. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/oecd-employment-outlook-2021_5a700c4b-en .

- 3. Labor Standards Act. Updated 2018]. Accessed May 15, 2023]. https://law.go.kr/LSW/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=199151&viewCls=engLsInfoR&urlMode=engLsInfoR#0000 .

- 4. Arbeitszeitgesetz (ArbZG). Updated 2021]. Accessed May 15, 2023]. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/arbzg/BJNR117100994.html#BJNR117100994BJNG000200307 .

- 5. Code du travail. Updated 2021]. Accessed May 15, 2023]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/texte_lc/LEGITEXT000006072050?etatTexte=VIGUEUR&etatTexte=VIGUEUR_DIFF .

- 6. The Working Time Regulations 1998. Updated 2019]. Accessed May 15, 2023]. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1998/1833/part/II .

- 7. Labor Standards Act. Updated 2021]. Accessed May 15, 2023]. https://elaws.e-gov.go.jp/document?lawid=322AC0000000049 .

- 8. Ministry of Employment and Labor Notice 2022-40. Matters necessary to determine whether cerebrovascular disease or heart disease and musculoskeletal disease are recognized as occupational diseases. Updated 2022]. Accessed June 16, 2023]. https://law.go.kr/LSW/admRulInfoP.do?admRulSeq=2100000211032 .

- 9. Pega F, Náfrádi B, Momen NC, Ujita Y, Streicher KN, Prüss-Üstün AM, et al. Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000-2016: a systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int 2021;154:106595. 34011457.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Shin KS, Chung YK, Kwon YJ, Son JS, Lee SH. The effect of long working hours on cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease; a case-crossover study. Am J Ind Med 2017;60(9):753–761. 28766770.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 11. Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD. The WHO/ILO report on long working hours and ischaemic heart disease - conclusions are not supported by the evidence. Environ Int 2020;144:106048. 33051042.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Li J, Pega F, Ujita Y, Brisson C, Clays E, Descatha A, et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int 2020;142:105739. 32505014.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Descatha A, Sembajwe G, Pega F, Ujita Y, Baer M, Boccuni F, et al. The effect of exposure to long working hours on stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int 2020;142:105746. 32505015.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Gimeno D, Vahtera J, Elovainio M, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Long working hours and sleep disturbances: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Sleep 2009;32(6):737–745. 19544749.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG, et al. Long working hours and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol Med 2011;41(12):2485–2494. 21329557.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Kim KU, Park SG, Kim HC, Lim JH, Lee SJ, Jeon SH, et al. Association between long working hours and suicidal ideation. Korean J Occup Environ Med 2012;24(4):339–346.ArticlePDF

- 17. Kleppa E, Sanne B, Tell GS. Working overtime is associated with anxiety and depression: the Hordaland Health Study. J Occup Environ Med 2008;50(6):658–666. 18545093.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Kim I, Kim H, Lim S, Lee M, Bahk J, June KJ, et al. Working hours and depressive symptomatology among full-time employees: results from the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2007-2009). Scand J Work Environ Health 2013;39(5):515–520. 23503616.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Choi E, Choi KW, Jeong HG, Lee MS, Ko YH, Han C, et al. Long working hours and depressive symptoms: moderation by gender, income, and job status. J Affect Disord 2021;286:99–107. 33714177.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Park S, Kook H, Seok H, Lee JH, Lim D, Cho DH, et al. The negative impact of long working hours on mental health in young Korean workers. PLoS One 2020;15(8):e0236931. 32750080.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Lee HE, Kim I, Kim HR, Kawachi I. Association of long working hours with accidents and suicide mortality in Korea. Scand J Work Environ Health 2020;46(5):480–487. 32096547.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Wagstaff AS, Sigstad Lie JA. Shift and night work and long working hours--a systematic review of safety implications. Scand J Work Environ Health 2011;37(3):173–185. 21290083.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Dembe AE, Erickson JB, Delbos RG, Banks SM. The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: new evidence from the United States. Occup Environ Med 2005;62(9):588–597. 16109814.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 24. Vegso S, Cantley L, Slade M, Taiwo O, Sircar K, Rabinowitz P, et al. Extended work hours and risk of acute occupational injury: a case-crossover study of workers in manufacturing. Am J Ind Med 2007;50(8):597–603. 17594716.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, Cronin JW, Rosner B, Speizer FE, et al. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med 2005;352(2):125–134. 15647575.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Fransen M, Wilsmore B, Winstanley J, Woodward M, Grunstein R, Ameratunga S, et al. Shift work and work injury in the New Zealand Blood Donors’ Health Study. Occup Environ Med 2006;63(5):352–358. 16621855.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 27. Dong X. Long workhours, work scheduling and work-related injuries among construction workers in the United States. Scand J Work Environ Health 2005;31(5):329–335. 16273958.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Lee JY, Choi E, Lim SH, Kim HA, Jung HS. The relationship between long working hours and industrial accident. Korean J Occup Health Nurs 2014;23(1):39–46.Article

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

Labor hour regulations in major countries

Long working hours and cerebro-cardiovascular disease

| Reference | Year | Study design | Exposure (working hours) | Outcome | Risk estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shin et al. [10] | 2017 | Case-crossover study | 10-hour increase in average weekly working hours | Cerebro-cardiovascular disease (incidence) | OR: 1.45 (1.22–1.72) |

| Kivimäki et al. [11] | 2015 | Meta-analysis | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Ischemic heart disease (mortality) | RR: 1.08 (0.94–1.23) |

| Stroke (incidence) | RR: 1.33 (1.11–1.61) | ||||

| Li et al. [12] | 2020 | Meta-analysis | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Ischemic heart disease (incidence) | RR: 1.13 (1.02–1.26) |

| Ischemic heart disease (mortality) | RR: 1.17 (1.05–1.31) | ||||

| Descatha et al. [13] | 2020 | Meta-analysis | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Stroke (incidence) | RR: 1.35 (1.13–1.61) |

| Stroke (mortality) | RR: 1.08 (0.89–1.31) |

Long working hours and sleep/mental health

| Reference | Year | Study design | Exposure (working hours) | Outcome | Risk estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtanen et al. [14] | 2009 | Cohort study | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Shortened sleep | OR: 3.24 (1.45–7.27) |

| Difficulty falling asleep | OR: 6.66 (2.64–16.83) | ||||

| Early morning awakening | OR: 2.23 (1.16–4.31) | ||||

| Virtanen et al. [15] | 2009 | Cohort study | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Depressive symptom | HR: 1.66 (1.06–2.61) |

| Anxiety symptom | HR: 1.74 (1.15–2.61) | ||||

| Kleppa et al. [17] | 2008 | Cross-sectional study | 49–100 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week (men) | Anxiety caseness | OR: 1.67 (1.36–2.06) |

| Depression caseness | OR: 1.50 (1.17–1.93) | ||||

| 41–100 hr/week vs. 32–40 hr/week (women) | Anxiety caseness | OR: 1.44 (1.06–1.95) | |||

| Depression caseness | OR: 1.61 (1.06–2.45) | ||||

| Kim et al. [18] | 2013 | Cross-sectional study | ≥ 60 hr/week vs. <52 hr/week | Depressive symptom | OR: 1.62 (1.20–2.18) |

| Choi et al. [19] | 2021 | Cross-sectional study | ≥ 69 hr/week vs. 40 hr/week | Depression (moderate to severe) | OR: 2.05 (1.22–3.42) |

| Suicidal ideation | OR: 1.93 (1.22–3.06) | ||||

| Park et al. [20] | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | > 60 hr/week vs. 31–40 hr/week | High stress level | OR: 2.55 (1.67–3.62) |

| Depression | OR: 4.09 (1.59–10.55) | ||||

| Suicidal ideation | OR: 5.30 (1.61–17.42) | ||||

| Kim et al. [16] | 2012 | Cross-sectional study | ≥ 60 hr/week vs. 40–51 hr/week | Suicidal ideation | OR: 1.38 (p-value 0.02) |

| Lee et al. [21] | 2020 | Cohort study | 45–52 hr/week vs. 35–44 hr/week | Suicide | HR: 3.89 (1.06–14.29) |

| > 52 hr/week vs. 35–44 hr/week | HR: 3.74 (1.03–13.64) |

Long work hours and accidents

| Reference | Year | Study design | Exposure (working hours) | Outcome | Risk estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dembe et al. [23] | 2005 | Cohort study | Overtime (yes vs. no) | Injuries or illnesses | HR: 1.61 (1.22–1.72) |

| Extended hours/week ≥ 60 (yes vs. no) | HR: 1.23 (1.05–1.45) | ||||

| Extended hours/day ≥ 12 (yes vs. no) | HR: 1.37 (1.16–1.59) | ||||

| Vegso et al. [24] | 2007 | Case-crossover study | > 64 hr/week vs. ≤ 40 hr/week | Occupational injury | HR: 1.88 (1.16–3.05) |

| Barger et al. [25] | 2005 | Case-crossover study | Extended work shifts ≥ 24 hr (yes vs. no) | Motor vehicle crashes | OR: 2.3 (1.6–3.3) |

| Fransen et al. [26] | 2006 | Cross-sectional study | > 40 hr/week vs. ≤ 40 hr/week | Work injury | RR: 1.32 (1.12–1.55) |

| Dong [27] | 2005 | Cross-sectional study | > 50 hr/week vs. ≤ 50 hr/week | Severe work-related injuries | OR: 1.98 (1.88–2.05) |

| Lee et al. [28] | 2014 | Cross-sectional study | ≥ 52 hr/week vs. < 52 hr/week (company) | Industrial accidents | OR: 2.29 (1.08–4.87) |

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- Gender differences in the association between long working hours and the onset of depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older workers in Korea: A population-based longitudinal study (2006–2022)

Seong-Uk Baek, Yu-Min Lee, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Maturitas.2025; 193: 108175. CrossRef - Occupational disease monitoring by the Korea Occupational Disease

Surveillance Center: a narrative review

Dong-Wook Lee, Inah Kim, Jungho Hwang, Sunhaeng Choi, Tae-Won Jang, Insung Chung, Hwan-Cheol Kim, Jaebum Park, Jungwon Kim, Kyoung Sook Jeong, Youngki Kim, Eun-Soo Lee, Yangwoo Kim, Inchul Jeong, Hyunjeong Oh, Hyeoncheol Oh, Jea Chul Ha, Jeehee Min, Chul

The Ewha Medical Journal.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Insight inTo Stress and POOping on Work TIME (ITS POO TIME): Protocol for a Web-Based, Cross-Sectional Study

Phillip John Tully, Suzanne Cosh, Gary Wittert, Sean Martin, Andrew Vincent, Antonina Mikocka-Walus, Deborah Turnbull

JMIR Research Protocols.2025; 14: e58655. CrossRef - Association of social jetlag with cigarette smoking, smoking intensity, and quitting intentions among Korean workers

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Journal of Public Health.2025; 47(3): 610. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and poor cardiovascular health assessed by the American Heart Association’s “Life’s essential 8”: findings from a nationally representative sample of Korean workers (2014–2021)

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Postgraduate Medical Journal.2025; 101(1200): 980. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease: a nationwide population-based study in Korea

S.-U. Baek, J.-U. Won, Y.-M. Lee, J.-H. Yoon

Public Health.2024; 232: 188. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and engagement in preventive healthcare services in Korean workers: Findings from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Seong-Uk Baek, Yu-Min Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon

Preventive Medicine.2024; 180: 107849. CrossRef - Long Working Hours, Work-life Imbalance, and Poor Mental Health: A Cross-sectional Mediation Analysis Based on the Sixth Korean Working Conditions Survey, 2020–2021

Seong-Uk Baek, Yu-Min Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon, Jong-Uk Won

Journal of Epidemiology.2024; 34(11): 535. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and the onset of problematic alcohol use in young workers: A population-based longitudinal analysis in South Korea

Seong-Uk Baek, Jong-Uk Won, Jin-Ha Yoon

Journal of Affective Disorders.2024; 344: 141. CrossRef - Changes in Korea’s working time policy: the need for research on flexible working hours considering socioeconomic inequality

Inah KIM

Industrial Health.2024; 62(2): 77. CrossRef - Effect of long working hours on psychological distress among young workers in different types of occupation

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Preventive Medicine.2024; 179: 107829. CrossRef - Association between long working hours and the development of suicidal ideation among female workers: An 8-year population-based study using the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women & Family (2012–2020)

Seong-Uk Baek, Yu-Min Lee, Jin-Ha Yoon

Psychiatry Research.2024; 333: 115731. CrossRef - Long working hours and preventive oral health behaviors: a nationwide study in Korea (2007–2021)

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon, Yu-Min Lee, Jong-Uk Won

Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine.2024; 29: 48. CrossRef - Special Series I: Working hours as a social determinant of workers’ health

Kyunghee Jung-Choi, Tae-Won Jang, Mo-Yeol Kang, Jungwon Kim, Eun-A Kim

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Association between long working hours and cigarette smoking, leisure-time physical activity, and risky alcohol use: Findings from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2014–2021)

Seong-Uk Baek, Jin-Ha Yoon

Preventive Medicine.2023; 175: 107691. CrossRef

Fig. 1

| Country (year of amendment of the statute) | Statutory normal daily working hours | Statutory normal weekly working hours | Additional information regarding working hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Korea (2018) | 8 hours | 40 hours | Statutory limit on maximum weekly hours (including overtime) are 52 hours. |

| Germany (2020) | 8 hours (with a maximum of 2 additional hours) | 40 hours | Adjustments are made to ensure that the average daily working hours do not exceed 8 hours within a 6-month or 24-week period. |

| France (2000) | No statutory provisions (maximum daily working hours is 10) | 35 hours (maximum weekly working hours limited to 48) | The average working hours over a period of 12 weeks cannot exceed 44. |

| Statutory limit on maximum yearly hours (including overtime) is 1,600. | |||

| United Kingdom (2019) | 8 hours | 40 hours (maximum working hours per week are 48 hours) | Working beyond 48 hours per week is allowed, but the UK government has not set legal limits for overtime work and pay. These are determined by agreements between employers and employees. |

| Japan (2018) | 8 hours | 40 hours | Statutory limits on overtime: 45 hours per month, and 360 hours per year. |

| Reference | Year | Study design | Exposure (working hours) | Outcome | Risk estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shin et al. [ | 2017 | Case-crossover study | 10-hour increase in average weekly working hours | Cerebro-cardiovascular disease (incidence) | OR: 1.45 (1.22–1.72) |

| Kivimäki et al. [ | 2015 | Meta-analysis | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Ischemic heart disease (mortality) | RR: 1.08 (0.94–1.23) |

| Stroke (incidence) | RR: 1.33 (1.11–1.61) | ||||

| Li et al. [ | 2020 | Meta-analysis | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Ischemic heart disease (incidence) | RR: 1.13 (1.02–1.26) |

| Ischemic heart disease (mortality) | RR: 1.17 (1.05–1.31) | ||||

| Descatha et al. [ | 2020 | Meta-analysis | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Stroke (incidence) | RR: 1.35 (1.13–1.61) |

| Stroke (mortality) | RR: 1.08 (0.89–1.31) |

| Reference | Year | Study design | Exposure (working hours) | Outcome | Risk estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtanen et al. [ | 2009 | Cohort study | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Shortened sleep | OR: 3.24 (1.45–7.27) |

| Difficulty falling asleep | OR: 6.66 (2.64–16.83) | ||||

| Early morning awakening | OR: 2.23 (1.16–4.31) | ||||

| Virtanen et al. [ | 2009 | Cohort study | ≥ 55 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week | Depressive symptom | HR: 1.66 (1.06–2.61) |

| Anxiety symptom | HR: 1.74 (1.15–2.61) | ||||

| Kleppa et al. [ | 2008 | Cross-sectional study | 49–100 hr/week vs. 35–40 hr/week (men) | Anxiety caseness | OR: 1.67 (1.36–2.06) |

| Depression caseness | OR: 1.50 (1.17–1.93) | ||||

| 41–100 hr/week vs. 32–40 hr/week (women) | Anxiety caseness | OR: 1.44 (1.06–1.95) | |||

| Depression caseness | OR: 1.61 (1.06–2.45) | ||||

| Kim et al. [ | 2013 | Cross-sectional study | ≥ 60 hr/week vs. <52 hr/week | Depressive symptom | OR: 1.62 (1.20–2.18) |

| Choi et al. [ | 2021 | Cross-sectional study | ≥ 69 hr/week vs. 40 hr/week | Depression (moderate to severe) | OR: 2.05 (1.22–3.42) |

| Suicidal ideation | OR: 1.93 (1.22–3.06) | ||||

| Park et al. [ | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | > 60 hr/week vs. 31–40 hr/week | High stress level | OR: 2.55 (1.67–3.62) |

| Depression | OR: 4.09 (1.59–10.55) | ||||

| Suicidal ideation | OR: 5.30 (1.61–17.42) | ||||

| Kim et al. [ | 2012 | Cross-sectional study | ≥ 60 hr/week vs. 40–51 hr/week | Suicidal ideation | OR: 1.38 ( |

| Lee et al. [ | 2020 | Cohort study | 45–52 hr/week vs. 35–44 hr/week | Suicide | HR: 3.89 (1.06–14.29) |

| > 52 hr/week vs. 35–44 hr/week | HR: 3.74 (1.03–13.64) |

| Reference | Year | Study design | Exposure (working hours) | Outcome | Risk estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dembe et al. [ | 2005 | Cohort study | Overtime (yes vs. no) | Injuries or illnesses | HR: 1.61 (1.22–1.72) |

| Extended hours/week ≥ 60 (yes vs. no) | HR: 1.23 (1.05–1.45) | ||||

| Extended hours/day ≥ 12 (yes vs. no) | HR: 1.37 (1.16–1.59) | ||||

| Vegso et al. [ | 2007 | Case-crossover study | > 64 hr/week vs. ≤ 40 hr/week | Occupational injury | HR: 1.88 (1.16–3.05) |

| Barger et al. [ | 2005 | Case-crossover study | Extended work shifts ≥ 24 hr (yes vs. no) | Motor vehicle crashes | OR: 2.3 (1.6–3.3) |

| Fransen et al. [ | 2006 | Cross-sectional study | > 40 hr/week vs. ≤ 40 hr/week | Work injury | RR: 1.32 (1.12–1.55) |

| Dong [ | 2005 | Cross-sectional study | > 50 hr/week vs. ≤ 50 hr/week | Severe work-related injuries | OR: 1.98 (1.88–2.05) |

| Lee et al. [ | 2014 | Cross-sectional study | ≥ 52 hr/week vs. < 52 hr/week (company) | Industrial accidents | OR: 2.29 (1.08–4.87) |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RR: relative risk.

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; HR: hazard ratio.

CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; OR: odds ratio; RR: relative risk.

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite