Abstract

-

Background

The purpose of this study is to describe the kinematic characteristics of manual weaving related to the biomechanical risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders.

-

Methods

Twelve professional female weavers participated in this study. The video recording of their workstations was performed perpendicularly in the sagittal and transverse planes in a synchronized manner, at about 2.45 m and for 5 minutes. The videos were then analyzed using the Kinove software. Statistical processing by the statistical SPSS 22 software.

-

Results

The results identified a succession of cycles, each with two important phases called the “interlacing” phase and the “winding/adjustment” phase. The average cycle time is 127.9 ± 11.7 seconds. The “interlacing” phase is the longest and concerns an average 80% of the cycle time or 103.5 ± 35.9 seconds. The segmental movements are mainly flexion-extension type with angular variations constantly above the acceptable limits. It is the same for the repetitiveness of the movements which solicit the upper limb and the trunk particularly.

-

Conclusions

These results recommend one of the actions to prevent musculoskeletal disorders including instructions on postures and frequencies of weaving movements as well as physical exercises adapted to the physical needs of practitioners.

-

Keywords: Burkina Faso; Musculoskeletal diseases; Handweaving posture; Exercise; Risk factors

BACKGROUND

The manual loincloth weaving is one of the income-generating activity of women in Burkina Faso. It employs more than 50,000 weavers including 40,000 women.

1 This activity is identified as a promising economic sector by prospective studies of investment sectors carried out by the government of Burkina Faso and its partners. It is widely acknowledged that this sector makes a significant contribution to the socio-economic autonomy of women, who represent approximately 90% of weavers.

2 However, it remains an informal activity with the main units of production (90%) operating in families. Consequently, this sector does not benefit from a health and safety framework.

On the other hand, several studies have shown the high prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among practitioners. Indeed, the literature reports a prevalence ranging from 80% to 100% of MSD cases among weaving practitioners.

3-6 These disorders are mostly consequences of poor work organization and/ or work-related physical load. Without a health and safety framework, the MSDs led weavers to self-medication with the worst unassessed consequences.

Many methods of prevention and care are described in the literature.

7-9 They include, among other things, ergonomic intervention on the workstations and on the physical capabilities of the worker. These methods according to the World Health Organization, are based on creating an appropriate balance between task requirements and the worker capacity, either by adapting the task to the human being by the layout of the workplace, either by developing the worker’s capacity for this task through practice and vocational training.

10 Among the various methods proposed in the literature, the Malchaire and Indeteege’s method

11 appears coherent and complete. Indeed, these authors propose a coherent, objective, and reasoned structuring of the workplace analysis involving the methods of quantification of all risk factors likely to be at the origin of MSDs of the upper limbs.

11 In this approach, the quantitative analysis of biomechanical stress (postures, levels of effort, and repetitiveness) based on observations from video recordings, is a major swatch of the prevention approach.

Manual weaving has been able to adapt to the modernization of societies in almost all continents, particularly in Asia and Africa, despite technical and technological advances.

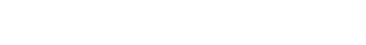

12-14 It is described as a series of skills and techniques that clearly present a set of physical loads detrimental to the musculoskeletal system. However, there is no study on the biomechanical characteristics of this activity as conducted by weavers in Burkina Faso. They use improved Sudanese-style horizontal pedal “looms” (

Fig. 1) introduced in the late 1950s by a congregation of nuns in Burkina Faso to solve a women’s profitability problem in their weaving activity.

2 Its working principle is similar to the traditional craft, but according to the author, the introduction of the stool and the flat pedals makes the techniques relating to the different parts of the body that it solicits different. Indeed, its operation consists in alternately operating one and the other heddle thanks to her feet, to open the space in which is slipped with one hand the shuttle which executes the frame. Each time the weft crosses the warp, it is pressed with the other hand by a comb attached to the second high bar of the craft. As all these tasks are carried out, the loincloth is wound on a cylinder placed at the front of the craft and called cloth roll or front beam as indicated in

Fig. 2.

15,16

This study aims to make a quantitative analysis of manual weaving activity to identify possible biomechanical constraints that can contribute to the prevention of MSDs among weavers. Specifically, it must lead to a mechanical description of weaving activity on the one hand and on the other hand to the identification of biomechanical risk factors of MSDs.

METHODS

The analysis was carried out female manual weavers operating on horizontal looms of improved pedal types in the Godé weaving workshop. The weavers having taken part in the study were chosen based on the following criteria. They had to be regular weaver employees in the Center Godé with the weaving as permanent activity. They had also to have a length of practice of weaving at least 12 months, and to accept the collection of the data. The center of Godé has been selected because it is the only center framed by the state and this fact offers some of the best conditions for our study in terms of space and availability of the weavers. The video recording took place August 22, 2019 in Godé Center where a hall has been arranged in a lighted place. All the 12 female weavers who met the criteria of the study on the day of the recording proceeding have been recorded. To make it possible to observe the weaving postures, the weavers were invited to wear space-saving clothes, in particular, tight-fitting bras. In addition, they were informed about the study's purpose and were regularly invited to work as simply as possible as they usually do. They were therefore encouraged to weave in a natural way as they used to. Their postures and movements were recorded during the weaving process.

Two Sony Handycam DCR-SR80 (25× Optical zoom; 800× digital zoom) video cameras were used for video recording. The recording procedure was inspired by that proposed by Croteau.

17 The video recording was performed in the sagittal and transverse planes in a synchronized manner. Each camera was adjusted and held by a cameraman and positioned perpendicular to the weaving station at approximately 2.45 m and recording was performed for 5 minutes after the weaver was installed on her workstation to weave.

17

The Kinovea software version 0.8.15 was used for the measurement of angles, frequencies of movements, and postures. It is software that has been designed for capture, observation, and motion analysis. It can also be used to track the trajectory and speed of point movement.

18,19

The approach of analysis adopted in this study was an adaptation of the method proposed by Malchaire and Indeteege

11 but using two cameras. It consisted of replaying the videos using Kinovea software to observe in each plan of recording, the following variables.

The kinematic characteristics of weaving, such as the types of segmental movements and their frequencies as well as the different postures of the back and the upper limbs were measured. These observed postures were compared to a set of reference postures defined in the literature.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics version 22 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were mainly used for data analysis.

Ethics statement

The research protocol was approved too by the national ethic committee of Burkina Faso in resolution No. 2017-10-154. It was also approved by the research ethics committee of the Institute of Sports, Sciences and Human Development. Study participants were informed in detail about the purpose and approach of this study. A briefing note from the research participant was sent to them.

RESULTS

General characteristics of participants

Twelve professional female weavers were recorded and analyzed.

Table 1 shows their characteristics. Their average age indicates adults with significant work experience in this activity.

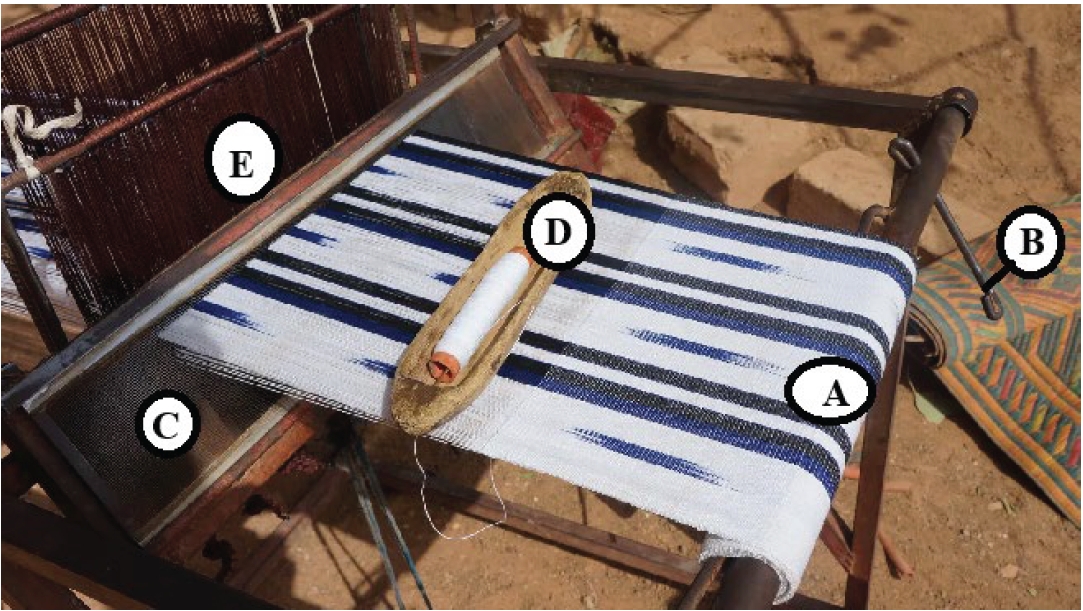

The analysis of the videos collected made it possible to identify a cycle with two important phases represented in the following

Figs. 3 and

4. These two phases are as follows.

- The phase that we named “interlacing”: it corresponds to the sequences of movements that allow the constitution of the frame that is to say the passage of the thread in the chain and the settlement of the frame.

The interlacing phase is a cyclical phase of alternating movements between the two upper limbs (

Fig. 3). The hands pass in turn the shuttle through the chain of wires (sequences A and B) followed by a movement of compaction of the comb to compact the woven tape (sequences C and D).

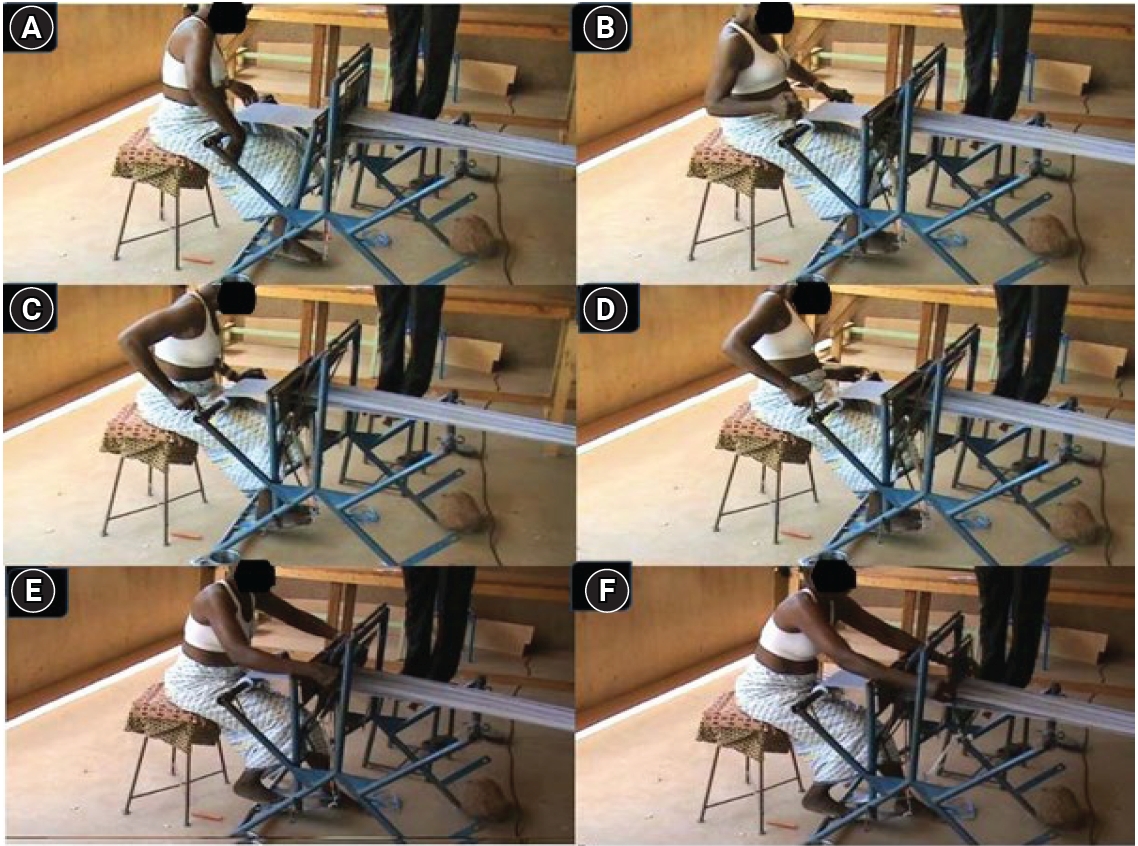

- The phase that we named “winding/ adjustment” of the woven strip. This phase consists of two stages, namely the winding itself to form a roll of strip already woven to free up space necessary for the continuation of the interlacing phase and the adjustment step which consists in returning the smooth to its normal position.

Winding: at this level, the weaver uses an arm that is used to turn towards her a metal lever attached to the beam of the loom to pull the string of wires stretched by a slide (

Fig. 4A-

D).

Adjustment: the weaver adjusts the stringers and the thread chain before resuming the interlacing operation (

Fig. 4E and

F).

The average cycle time is 127.9 ± 11.7 seconds (2 minutes and 7.9 seconds). The “interlacing” phase is the longest and concerns on average 80% of the cycle time or 103.5 ± 35.9 seconds (

Table 2).

In the phase of interlacing,

Table 3 shows that the joints of the upper limb, particularly the shoulder, elbow and wrist, are solicited in the three planes of movement. However, since the videos were not filmed in the frontal plane, the abduction, and inclination movements were not measured. The forearm is used between 49° and 89° in extended flexion and the arm between 10 and 25°. The different sequences (A to D) of this phase are illustrated in

Fig. 3.

Through the same table, we can read the nature of the different postures of the trunk and segments of the upper limb during winding. During this sequence, the two upper limbs are solicited differently. For all weavers, the position of the lever of the loom requires more mobilization of the right member. Under the registration plan, the data of the right member could be recorded. The trunk and the arm are solicited in all plans. The right arm is the most stressed with movements ranging from 59° in extension to about 10° in bending. The same applies to the back, which oscillates between –13° and 25°. The different sequences (A to D) of this phase are illustrated in

Fig. 2. The same movements of flexion and extension are observed in the adjustment phase (

Fig. 4E and

F).

DISCUSSION

As a reminder, our study aim is to describe the kinematic characteristics of manual weaving in order to contribute to the reflection on the biomechanical risk factors of musculoskeletal disorders related to this activity.

The average age of women who took part in this stage of the research is 48.7 ± 15.2 years old with an average working time of 19.8 ± 13.7 years. The average age of women indicates that they are adults and have extensive professional experience in this activity. With this maturity and experience, they have certainly developed automatisms and adaptations that make their weaving work much more professional, and free of parasitic actions.

17,21 Thus, this professional experience seems more interesting in an epidemiological study such as the present insofar as the constraints or risks related to the activity could be reduced to the minimum due to gestural control.

In this regard, the video recordings of the weaving were made in the sagittal and transversal planes and their analysis allowed to identify a cycle of two major phases in the weaving activity during which all the joints of the upper limb and trunk are mobilized. The cycle lasts on average 2 minutes and 8 seconds with the “interlacing” phase as the longest with an average of 80% of the cycle time or 103.5 ± 35.9 seconds. When the weaver weaves the string of threads, she interrupts this operation on average after two minutes to wind the strip she gets. This second winding operation takes on average 8% of the cycle time. Weaving can therefore be considered as a set of cycles comprising interweaving operations of wire interspersed by winding operations of woven strips. These steps actually respond to the general principles of fabric manufacturing described in the literature. Indeed, the fabric is defined as the result of an assembly of threads, fibers, or both.

22 Referring to the definitions of weaving by some authors, it appears that the two phases observed correspond one to the mechanisms of assembly, it is the interlacing and the other to the constitution of the texture.

15,16 In fact, the physical stresses of the different weaving phases take into account the mean time of the phase, the frequency of segmental repetitions and the amplitude of the angles of the solicited segments.

5,7,23

In this respect, there is a predominance of flexion-extension movements. The horizontal shape of the loom could explain this observation. In fact, this elongated forward shape requires the weaver to use weaving techniques that lead to movements in the forward-backward direction in the sagittal plane, which probably corresponds to bending-extension movements.

24-26

Inside a weaving cycle that lasts on average 2 minutes 8 seconds, the nature and intensity of mobilization of the joint system of the upper limb and trunk are not the same. For the upper limb, the results obtained from the recordings analysis indicate repeated stress at the elbow and shoulder joints especially during the interlacing operation (80% of the time of the cycle). Indeed, the joints of each upper limb regularly perform movements of various flexion-extensions between two interruptions, rotation, and abduction during the interlacing operation. In the literature, the repetitiveness of a movement becomes a MSD risk factor when the cycle time is less than 30 seconds or when more than 50% of the cycle time is composed of the same sequences of gestures

11,27,28 or this movement reaches 15 repetitions per minute.

29

In this case, the interlacing phase occupies 80% of the cycle and is composed of 103 sequences of repeated movements: 51 sequences of “shuttle passage” and 51 sequences of “compaction of the frame.” These characteristics are more than 30% higher than the criteria of repetitiveness cited above reported in the literature.

11,27,29 This means that FDF weaving is a highly repetitive activity, especially its interlacing phase.

As regards the angular values collected in this phase, they also show an amplitude of bending elbow and shoulder extensions around 10° and 20° from the vertical with abduction and shoulder rotation. These variations reveal both the multitude of actions during weaving, but also the movements constraints related to the shape and dimensions of the “loom” which impose adaptation postures. For shoulders, these values are within the range of ergonomic standards prescribed in the literature.

20,30-33 According to these authors, the maximum acceptable angles of arm posture are 20° for abduction and 25° for flexions, which approximately agree with our results for flexion.

About the back, the results reveal a joint amplitude of the trunk in flexion-extension during this interlacing operation of about 7° to 11° of the vertical. These variations follow those of the segments of the upper limb because the movements of the trunk generally extend to those of the upper limb. These values remain appropriate as they are within the comfort zone.

34,35 Therefore, joint mobilization does not appear to be a potential risk factor for lower back pain in the interlacing phase, but it presents high risks in terms of repetitive movements. The postural analysis of the second phase of the weaving cycle, especially the winding, indicates that in terms of duration, it is shorter (8.39%) of the cycle time or 10.74 seconds on average. In terms of repetitiveness of movements, it has fewer demands on joint structures. On the other hand, the angles described by the segments mobilized are more important during this operation. Indeed, the results present at the level of the upper limb a set of abduction, bending, and rotation movements for the shoulders and elbow of the limb that performs the winding. Subsequently, there is a pronounced bending of the two limbs to adjust smoothly. For the shoulder, the mean observed angles are 59° in extension and 10° in bending combined with abduction movements. For the different authors, a bending-extension of the arms is acceptable below 20°, both in extension and in flexion, beyond, the shoulders are exposed to a risk of MSDs.

31,34 These data from the literature support the fact that the joint stress of the shoulders during this second weaving operation also appears as an important risk factor for MSDs especially in extension because the angular mean values are extreme, over 59°.

For the back, the results obtained indicate during the winding operation the presence of flexion-extension movements. Indeed, the bending-extension movements vary on average between 13° in extension and 25° in bending angle. The literature considers that the trunk is in a neutral bending position in a sagittal plane between 0° and 20° which assumes a physical stress of high risk in extension and less in bending.

31,36 However, other authors estimate that a trunk bend of 20° angle on a seat without inclination and average height lower than the height of the work support (loom in the case of weaving) significantly reduces the trunk-thigh angle. This reduction of the angle below 100° does not allow the physiological lumbar curvature to maintain so the pelvis switches to retroversion favoring the risk of lumbar pain. Moreover, this sitting posture of work if maintained for long hours can be a source of lumbar pain, especially with twisting movements during this winding phase.

29,37 In the literature, some authors who used tools of empirical observation came to the same conclusions. Indeed, Choobineh et al.

26 through empirical observation and literature review find that carpet weaving is in fact a very repetitive task in which a regular weaver makes up to 30 knots per minute. They noticed that during all stages of weaving, wrist and finger flexors and extensors are used repeatedly, with pinch movements and gripping force. They showed that the weaving task represents 60% of the weavers’ total working time. Therefore, they concluded that in weaving, repetitive movement is common. Since very repetitive tasks have cycle lengths of 30 seconds or less, they classify weaving as very repetitive work.

26 The same authors studied the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders and the design of manual carpet weaving workstation. In that study, they argue that in a weaving operation the positions of the head, neck, and shoulders are decisive in the ergonomic design of a weaving workstation.

38 For them, the trunk posture is an essential element in the design of a weaving seat.

38 The results of their study highlight the risk factors of weaving in general, but they cannot be compared to the results of this study since the loom used in our case is horizontal while it is vertical in the case of carpet weaving. The same observations are made through the studies of Motamedzade et al.

14,39 and that of Bazrafshan and Mahmoudi.

40

Moreover, our results confirm those of Dewangan and Sora

25 who did a similar study with 274 weavers including 200 women using questionnaires and goniometers. Their results revealed a large variation in most dimensions of looms. They also found that the body bending of weavers is relatively higher in horizontal looms compared to vertical looms. For them, musculoskeletal pain in the lower back and neck is widespread in most workers independently of looms. Posture, energetic effort, repetitive task, and work method were identified as the predominant causes of musculoskeletal pain reported by weavers regardless of the loom. Their study found that more than 95% of weavers reported musculoskeletal pain in any part of the body.

CONCLUSIONS

MSDs are now a health issue in the professional area. In Africa, and particularly in Burkina Faso, the phenomenon received little attention. This study focused on weavers and on their activity biomechanical characteristics. It is purely descriptive and analytical. It showed that weaving is a mechanically cyclical activity with increased solicitation of the upper limb and back in the sagittal plane. These results recommend not only a design with safe and preventive instructions based on the identified characteristics but also physical activity programs for conditioning of the different body parts according to the type of solicitation. However, it is important to mention that weaving is a process that involves several stages: dyeing, warping, and weaving the craft. The biomechanical analysis carried out concerned only one stage of the professional activity of the weaver. The results therefore suggest a broader analysis considering all the tasks of weaving given the possibility of a combination of physical requirements as a risk factor.

Abbreviations

NOTES

-

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Sawadogo A. Data curation: Sawadogo A, Nana B, Cissé AR, Ouédraogo B. Formal analysis: Sawadogo A, Cissé AR. Investigation: Sawadogo A, Nana B. Methodology: Sawadogo A, Ouédraogo B. Software: Sawadogo A. Validation: Sawadogo A, Nana B, Ouédraogo B. Resources: Sawadogo A, Nana B, Ouédraogo B. Writing - original draft: Sawadogo A. Writing - review & editing: Sawadogo A, Ouédraogo B

-

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their availability.

Fig. 1.Improved modern pedal loom. A, pulley; B, heddle; C, reed; D, front warp beam; E, lever; F, pedals; G, shuttle; H, coil; I, stool.

Fig. 2.General appearance of the Faso Dan Fani loincloth produced by weavers. A, Faso Dan Fani loincloth; B, lever; C, reed; D, shuttle; E, heddle.

Fig. 3.Sagittal view of the interlacing phase. (A) Change “to go” from shuttle to colored limb. (B) Strip compaction with uncolored limb. (C) Change “to go back” from shuttle to uncolored limb. (D) Strip compaction with colored limb.

Fig. 4.Sagittal view of the woven strip winding. (A, B) Rolled up from the front. (C, D) Rolled up from top to back. (E, F) Thrust and adjustment of the rails forward.

Table 1.Characteristics of the surveyed female weavers

|

Characteristic |

No. of participants (n = 12) |

|

Age (years) |

48.7 ± 15.6 |

|

Height (cm) |

163.1 ± 7 |

|

Mass (kg) |

65.5 ± 14.9 |

|

Working time (years) |

19.8 ± 13.7 |

|

Working weekly times (days) |

6 |

|

Working daily hours (hours) |

8.7 ± 0.5 |

Table 2.Times of the weaving cycle of the loincloth Faso Dan Fani

|

Phases |

Gesture sequences (fa) |

Average ± SD times per cycle (seconds) |

% of total cycle time |

|

Weaving cycle |

|

|

|

|

Interlacing |

Compacting (51 ± 1) |

103.5 ± 35.9 |

80.9 |

|

woof crossing (51 ± 1) |

|

Winding/adjustment |

Warp beam rotation (1) |

10.7± 2.7 |

8.4 |

|

Beam adjustment (1) |

|

Average cycle time (seconds) |

|

127.9 ± 11.7 |

100 |

Table 3.Description of the types of movements during the cycle

|

Body segments |

Movement |

Average angle (degree)

|

Recommended cut-point7,20 (degree) |

|

Interlacing phase (CTa = 103.5 ± 35.9) |

Winding/adjustment phase (CT = 10.7± 2.7) |

|

Hand |

Flexion-extension |

NEb

|

NE |

<45 |

|

Abduction-adduction |

NE |

NE |

0 |

|

Forearm |

Pronation-supination |

NE |

NE |

0 |

|

Flexion-extension |

49 ± 1 Fc–89 ± 3 F |

73 ± 2 F–85 ± 1 F |

<60 or >100 |

|

Arm |

Flexion-extension |

10 ± 7 F–25 ± 5 F |

59 ± 3 Ed–60 ± 5 F |

<20 |

|

Abduction-adduction |

NE |

NE |

<20 |

|

Rotation |

NE |

NOe

|

0 |

|

Back |

Flexion-extension |

7 ± 3–11 ± 9 |

13 ± 2 E–25 ± 5 F |

<20 F; 0 E |

|

Tilt |

NO |

NE |

0 |

|

Rotation |

NO |

NE |

<10 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Diarra M. Transformation artisanale du coton: quelle contribution à la création d’emplois pour les femmes et à la lutte [Artisanal processing of cotton: what contribution to the creation of jobs for women and to the fight]. In: Salon international du Coton et du Rextile (SICOT). Koudougou, Burkina Faso: Salon International du Coton et du Textile (SICOT)/Agence Burkinabè d’Investissement; 2018, 13.

- 2. Grosfilley A. Le tissage chez les Mossi du Burkina Faso: dynamisme d’un savoir-faire traditionnel [Weaving among the Mossi of Burkina Faso: the dynamism of traditional know-how]. Afr Contemp 2006;217(1):203–15.

- 3. Pandit S, Kumar P, Chakrabarti D. Ergonomic problems prevalent in handloom units of North East India. Int J Sci Res Publ 2013;3(1):1–7.

- 4. Nag A, Vyas H, Nag PK. Gender differences, work stressors and musculoskeletal disorders in weaving industries. Ind Health 2010;48(3):339–48.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Banerjee P, Gangopadhyay S. A study on the prevalence of upper extremity repetitive strain injuries among the handloom weavers of West Bengal. J Hum Ergol (Tokyo) 2003;32(1):17–22.PubMed

- 6. Sawadogo A, Nana B, Kabore A, Lawani MM, Sie MA, Yessoufou L. Musculoskeletal disorders among traditional loincloth weavers in Ouagadougou. Kinésithérapie Rev 2021;21(236-237):17–21.

- 7. Kuorinka I, Forcier L. Les lesions attribuables au travail repetitifs: ouvrage de référence sur les lésions musculo-squelettiques liées au travail [Repetitive Strain Injuries: A Reference Work on Work-Related Musculoskeletal Injuries]. Montreal, Canada: MultiMondes; 1995.

- 8. Denis D, St-Vincent M, Jette C, Imbeau D. Les pratiques d’intervention portant sur la prévention des troubles musculo-squelettiques: un bilan critique de la littérature [Intervention Practices for the Prevention of Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Critical Review of the Literature]. Montreal, Canada: IRSST; 2005.

- 9. National Research Council (NRC); Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace. Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace: Low Back and Upper Extremities. Washington, D.C., USA: National Academies Press; 2001.

- 10. World Health Organization. Glossaire de la promotion de la santé [Health Promotion Glossary]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999.

- 11. Malchaire J, Indesteege B. Troubles musculosquelettiques: analyse du risque [Musculoskeletal Disorders: Risk Analysis]. Bruxelles, Belgium: INRCT; 1997.

- 12. Raymond W, Kalilou S. Economie informelle [Informal economy]. In: de Verdiere M, editor. Rapport Afrique de l’Ouest 2007-2008 [West Africa Report 2007-2008]. Paris: CSAO/CEDEAO; 2009, 169–178.

- 13. Adanur S. Handbook of Weaving. Lancaster, PA, USA: CRC Press; 2000.

- 14. Motamedzade M, Choobineh A, Mououdi MA, Arghami S. Ergonomic design of carpet weaving hand tools. Int J Ind Ergon 2007;37(7):581–7.Article

- 15. Etienne-Nugue J. Artisanats traditionnels en Afrique Noire: Haute Volta [Traditional Crafts in Black Africa: Upper Volta]. Dakar, Senegal: Institut Culturel Africain; 1982.

- 16. Institut National des Metiers d’Art. Fiche métier d’art - Tisserand [Art Job Description: Weaver]. Paris, France: Institut National des Métiers d’Art; 2015.

- 17. Croteau G. Analyse biomécanique des positions segmentaires dans mouvement de couture en fonction de l’inclinaison du plan de travail et des phases du mouvement de couture [Biomechanical analysis of segmental positions in sewing movement as a function of the inclination of the work plane and the phases of the sewing movement]. PhD thesis. Quebec, Canada: Université du Quebec; 1995.

- 18. Hisham H, Nazri A, Herawati L, Mahmud J. Measuring ankle angle and analysis of walking gait using Kinovea. In: iMEDiTEC 2017: International Conference of Medical Device and Technology; 2017 Sep 6-7; Johor Bahru, Malaysia. p. 247–50.

- 19. Nor Adnan NM, Ab Patar MN, Lee H, Yamamoto SI, Lee JY, Mahmud J. Biomechanical analysis using Kinovea for sports application. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2018;342:012097.ArticlePDF

- 20. Demaret JP, Gavray F, Willems F, De Beeck RO, Gallez B. Prévention des troubles musculosquelettiques (TMS) dans le secteur de la construction [Prevention of Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Construction Sector]. Bruxelles, Belgium: SPF Emploi, Travail et Concertation Sociale; 2015.

- 21. Bourgeois F, Hubault F. From biomechanics to work valorization, analysing gesture in all dimensions. Activités 2005;2(1):20–36.

- 22. Dalal M. Contribution à l’étude de la saturation des tissus simples et multicouches: tissus 2D et 3D [Contribution to the Study of Saturation of Single and Multilayer Fabrics: 2D and 3D Fabrics]. Mulhous, France: Université de Haute Alsace; 2012.

- 23. Jones T, Kumar S. Comparison of ergonomic risk assessments in a repetitive high-risk sawmill occupation: saw-filer. Int J Ind Ergon 2007;37(9-10):744–53.Article

- 24. Choobineh A, Hosseini M, Lahmi M, Khani Jazani R, Shahnavaz H. Musculoskeletal problems in Iranian hand-woven carpet industry: guidelines for workstation design. Appl Ergon 2007;38(5):617–24.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Dewangan KN, Sora K. Job demand and human-machine characteristics on musculoskeletal pain among female weavers in India. In: Proceedings 19th Triennial Congress of the IEA; 2015 Aug 9-14; Melbourne, Australia. p. 1–8.

- 26. Choobineh A, Shahnavaz H, Lahmi M. Major health risk factors in Iranian hand-woven carpet industry. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 2004;10(1):65–78.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Demaret JP, Cavray F, Eeckelaert L, Beeck RO, Verjans M, Willems F. Prévention des troubles musculosquelettiques dans le secteur hospitalier [Prevention of Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Hospital Sector]. Bruxelles, Belgium: SPF Emploi, Travail et Concertation Sociale; 2010.

- 28. Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité pour la prévention des accidents du travail et des maladies professionnelles. Troubles Musculosquelettiques (TMS) [Musculoskeletal Disorders]. Paris, France: Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité; 2015, 1–27.

- 29. Daas B. Prevention des troubles musculosquelettiques du chirurgien-dentiste [Prevention of musculoskeletal disorders in the dentist]. PhD disseration. Nantes, France: Université de Nantes; 2012.

- 30. Smedile A. Apparition et prévention des troubles chez les interprètes en langue des signes française/français [Occurrence and Prevention of Disorders among French/French Sign Language Interpreters]. Villeneuve-d'Ascq, France: Université Charles de Gaulle Lille 3; 2008.

- 31. Roquelaure Y. Troubles musculo-squelettiques et facteurs psychosociaux au travail [Musculoskeletal Disorders and Psychosocial Factors at Work]. Bruxelles, Belgium: European Trade Union Institute; 2018.

- 32. Baillargeon M, Patry L. Les troubles musculo-squelettiques du membre supérieur reliés au travail: définitions, anatomie fonctionnelle, mécanismes physiopathologiques et facteurs de risque [Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Upper Limb: Definitions, Functional Anatomy, Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Risk Factors]. Montreal, Canada: Occupational Health and Environmental Health Unit, Public Health Department of Montreal-Centre; 2003.

- 33. Stellman JM. Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety. 3rd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office; 2015, 87.

- 34. McAtamney L, Nigel Corlett E. RULA: a survey method for the investigation of work-related upper limb disorders. Appl Ergon 1993;24(2):91–9.ArticlePubMed

- 35. Corlett EN. Static muscle loading and the evaluation of posture. In: Wilson JR, Corlett N, editors. Evaluation of Human Work. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Taylor & Francis; 2005, 453–496.

- 36. Omrane A, Kacem I, Heni M, Henchi A, Elmhami S, Merchaoui I, et al. Prevalence et determinants des troubles musculosquelettiques des membres superieurs chez les artisans tunisiens. East Mediterr Health J 2018;23(11):774–80.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Dujardin R. Étude de la prise en charge ostéopathique autour du poste de travail informatique [Study of Osteopathic Care around the Computer Workstation]. Loos, France: Institut supérieur d’ostéopathie Lille; 2018.

- 38. Choobineh A, Lahmi M, Hosseini M, Shahnavaz H, Jazani RK. Workstation design in carpet hand-weaving operation: guidelines for prevention of musculoskeletal disorders. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 2004;10(4):411–24.ArticlePubMed

- 39. Motamedzade M, Afshari D, Soltanian A. The impact of ergonomically designed workstations on shoulder EMG activity during carpet weaving. Health Promot Perspect 2014;4(2):144–50.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 40. Mahmoudi N, Bazrafshan M. A carpet-weaver's chair based on anthropometric data. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 2013;19(4):543–50.ArticlePubMed

, Brigitte Nana1

, Brigitte Nana1 , Brahima Ouédraogo2

, Brahima Ouédraogo2 , Abdoul Rahamane Cissé1

, Abdoul Rahamane Cissé1

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite