Abstract

-

Background

Mercury, particularly in its methylmercury form, significantly affects neurological and developmental functions. In Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea, blood mercury levels are elevated due to high fish consumption, especially shark meat. Vulnerable groups, such as pregnant women, are at increased risk as methylmercury can cross the placenta and accumulate in breast milk. This study aimed to investigate the risks of mercury exposure from shark meat consumption among young and middle-aged women in Gyeongsangbuk-do.

-

Methods

The data of women aged 19–55 years from the 2018 Gyeongsangbuk-do Community Health Survey were included. Survey questions focused on frequency and amount of shark meat consumption, as well as pregnancy status, recent childbirth, and breastfeeding status. The Complex Sample Analysis was used to determine the prevalence and risk of overconsumption. Weekly mercury intake was calculated for respondents who reported their body weight, and the population size exceeding Joint Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) and Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS)’s threshold was estimated.

-

Results

Regions where the consumption rate of shark meat exceeds the average for Gyeongsangbuk-do are found to be distributed in the southeastern part of the province. Population estimates revealed that approximately 9,895 women aged 19–55, including 255 who had breastfed in the past year, consumed shark meat exceeding the recommended intake. Based on the maximum recorded mercury concentration (8.93 µg/g), an estimated 2,645 women surpassed the JECFA’s mercury exposure threshold, while 845 exceeded the MFDS’s threshold.

-

Conclusions

In young and middle-aged women of Gyeongsangbuk-do, approximately 7.1% exceed the single intake limit, while up to 1.9% exceed the JECFA's provisional tolerable weekly intake (PTWI) and 0.6% exceed the MFDS's PTWI, suggesting considerable risk that warrants monitoring and guidance. More stringent advisory measures regarding shark meat consumption and updated standards on mercury concentration in shark meat are essential for young and middle-aged women in the province.

-

Keywords: Shark meat; Mercury exposure; Women; Young and middle-aged

BACKGROUND

Mercury is found in nature and can be produced by various industrial activities and distributed in the environment, including the air, soil, and water, or accumulates in living organisms.

1 Methylmercury is the most toxic form of mercury in the environment and is produced by aquatic microorganisms.

2 Since industrialization, mercury has been released into the environment on a large scale, resulting in massive exposure to methylmercury through consuming contaminated seafood. One such case is Minamata disease in Japan. In this case, neurological effects such as sensory disturbances in the extremities and subsequent ataxia, balance disorders, bilateral visual disturbances, gait disturbances, dysarthria, and muscle atrophy have been reported in adults exposed to mercury.

3 In addition, neurodevelopmental disorders and impaired digestive and musculoskeletal development have been reported in infants and young children of Minamata, due to prenatal exposure.

4,5 Although the mercury spill was not as severe as in the Minamata case, the risk of methylmercury exposure has been observed in areas where people consume large amounts of seafood, which tends to accumulate mercury in the body. Cohorts from the Faroe Islands, New Zealand, and the Seychelles Islands represent populations consuming more fish than other regions. Metaanalyses based on them have found a negative association between maternal hair mercury concentrations and intelligence quotient of their children.

6,7

Several studies have shown that the primary source of human exposure to methylmercury is the consumption of foods containing mercury. Ingested methylmercury is fully absorbed through the digestive system.

8 Methylmercury in the blood can cross the placenta. Therefore, if a pregnant woman is exposed to methylmercury, elevated blood methylmercury can cross the placenta and blood-brain barrier of the developing fetus.

8,9 Methylmercury is also found in breast milk, meaning newborns can be exposed through breastfeeding.

10 As the nervous system develops from fetus to adolescence, methylmercury exposure in the placenta and breast milk can interfere with normal neurological development, resulting in cognitive and motor impairments.

11-13 Therefore, women, especially who live in areas with high seafood consumption and could become pregnant or breastfeeding, can be identified as a vulnerable group for mercury, and their exposure to this substance should be carefully monitored.

Methylmercury concentrations appear to increase in organisms higher up the food chain. Sharks, a large fish, have higher mercury concentrations than other fish due to their position as top predators in the food chain.

14,15 Sharks absorb and concentrate mercury in their tissues by eating small fish and other prey. Their long lifespan increases the potential for high methylmercury concentrations.

The Republic of Korea has one of the highest rates of shark meat consumption worldwide.

16 In particular, the Gyeongsangbuk-do region in the southwest of the Korean Peninsula has long consumed shark meat as a traditional food. Yeongcheon, which is in southern-east part of Gyeongsangbuk-do, has been a transportation and logistics center for seafood coming from the East Coast for hundreds of years. Almost all shark meat distributed to the inland provinces of Gyeongsangbuk-do has passed through this region, which is said to supply 50% of the national shark meat consumption today.

17,18 Historically, to prevent spoilage during long transportation from the coast to the inland, shark meat was salted, which enhanced its lean and chewy characteristics, making it a gourmet food. It became a special food served to honor guests and was used as an essential dish in ancestral rites, which are conducted periodically.

17 Since the ancestral rite is still regarded as an important traditional custom in the Republic of Korea, shark meat has continued to be consumed regularly in Gyeongsangbuk-do.

According to the Korean National Environmental Health Survey, residents of Gyeongsangbuk-do had higher blood mercury levels (>7.0 µg/L) than the average for the Republic of Korea and the average for other countries.

19 In addition, a 2011 study by the Korea National Institute of Environmental Research examined shark meat consumption and blood mercury levels in different regions of Gyeongsangbuk-do and found that blood mercury levels increased linearly with increasing frequency and amount of shark meat consumption. Moreover, areas with high consumption coincided with areas with high blood mercury levels, indicating a relationship between shark meat consumption and blood mercury levels.

20 Additionally, a study by Baek et al.

21 revealed a correlation between the consumption of shark meat and increased blood mercury levels, leading to the assessment that shark meat consumption is indeed a significant risk factor that cannot be overlooked.

This study used data from the 2018 Korean Community Health Survey to determine shark meat consumption by young and middle-aged women in Gyeongsangbuk-do, in which shark meat consumption is a tradition and still actively marketed. In addition, this study aimed to suggest the potential risks of methylmercury exposure in vulnerable populations.

METHODS

This study was based on statistics from the 2018 Korean Community Health Survey of adults aged ≥19 years living in Gyeongsangbuk-do. The data are publicly available, and consent was obtained from Statistics Korea to use the raw data.

The target population of the 2018 Community Health Survey was adults aged ≥19 years (born before July 31, 1999). The survey sampled from a comprehensive list of the entire population, which used resident registration data from the Ministry of the Interior and Safety and housing data from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport. The sample size was then stratified by districts, towns or cities, and housing types to determine an average sample size of 900 people per health center in each district, with a target error of ±3%, and allocated to districts, towns, or cities, and housing types using a proportional distribution method. Sampling was conducted in two stages. The first sampling stage was based on the number of households by housing type within a ward/class/neighborhood, with the probability proportional sampling considering the size of the households. The second sampling stage was based on the number of households in the ward/class/neighborhood selected as sample points by cluster sampling. The raw survey data were weighted by person to reflect the household sampling rate, survey eligibility rate, proportion of households by housing types, and individual response rate and were used for analysis.

A total of 22,176 residents of Gyeongsangbuk-do participated in the 2018 Korean Community Health Survey, including 4,485 young and middle-aged women between 19 and 55 years, based on the menopausal age. Of these, 4,484 were selected for final analysis, excluding one who did not respond to the question, “Have you eaten shark meat (Dombaegi) in the past year?” The community health survey asked women between 19 and 55 years about their current pregnancy status, childbirth in the past year, and breastfeeding for at least 6 months in the past year (

Table 1).

In the questionnaire, participants were asked whether they had consumed shark meat in the past year, their frequency of shark meat consumption in the past year, and the amount of shark meat consumed per serving. Responses to whether they had consumed shark meat in the past year were dichotomized as yes/no, and only those who had consumed shark meat in the past year were asked to answer the frequency and amount of shark meat consumption. Respondents were divided into two groups based on the frequency of shark meat consumption: those who consumed shark meat only during festivals and rituals and those who consumed shark meat in addition to festivals and rituals. Those who consumed shark meat only during festivals and rituals were asked to indicate the number of festivals and rituals. Those who consumed shark meat in addition to festivals and rituals were asked to indicate the number of times per week, month, or year. For the amount of shark meat consumed, respondents were asked to select one of three options: (1) two fingers or less, (2) half-palm size, or (3) full-palm size or more, based on the sizes 25, 50, and 100 g, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The Korean Community Health Survey is a complex sample that includes stratification variables, cluster variables, and weights; therefore, we conducted a complex sample statistical analysis to reflect this.

The consumption rate was defined as the proportion of respondents who had eaten shark meat in the past year among all young and middle-aged women and was calculated by region in Gyeongsangbuk-do. We also used a complex sampling design to estimate the population of shark meat consumers by region. This was performed to determine the geographical distribution of areas with high shark meat consumption rates and the number of people consuming shark meat.

Population estimates were made using a complex sampling design for women who were pregnant at that time, had given birth within the past year, and had breastfed within the past year, as these are the populations at risk of fetal and neonatal mercury exposure from shark meat consumption. The estimated numbers, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and corresponding percentages of the population in each category were calculated.

The number of intakes was converted to the number per year (weekly intake × 52 weeks, monthly intake × 12 months) for better comparability, and the annual intake (annual intake × serving size) was calculated for each individual and used for statistical analysis. The mean, 95% CIs, and maximum values of the annual intake frequency and amount are presented for each of the following categories: current pregnancy, childbirth within 1 year, and breastfeeding within 1 year. To quantify the exposure over a year, the annual intake was calculated by multiplying the number of intakes per year by the number of intakes per serving. The maximum and mean annual intakes were calculated.

For young and middle-aged women who reported their weights in the survey, the weekly mercury intake from shark meat per kg of body weight was calculated and compared to the provisional tolerable weekly intake (PTWI) of Joint Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) and Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). For individuals exceeding these limits, we conducted population estimation and calculated the 95% CIs. A CI that did not include zero was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for analysis.

Ethics statement

The present study protocol was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of Yeungnam University (IRB No. 7002016-E-2023-074). It has been verified that the study is exempt from IRB review. The Community Health Survey used in this study was conducted with participants' informed consent, including notice regarding the use of personal information. The results are based on publicly accessible data, and the use of raw data was approved by Statistics Korea.

RESULTS

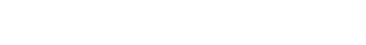

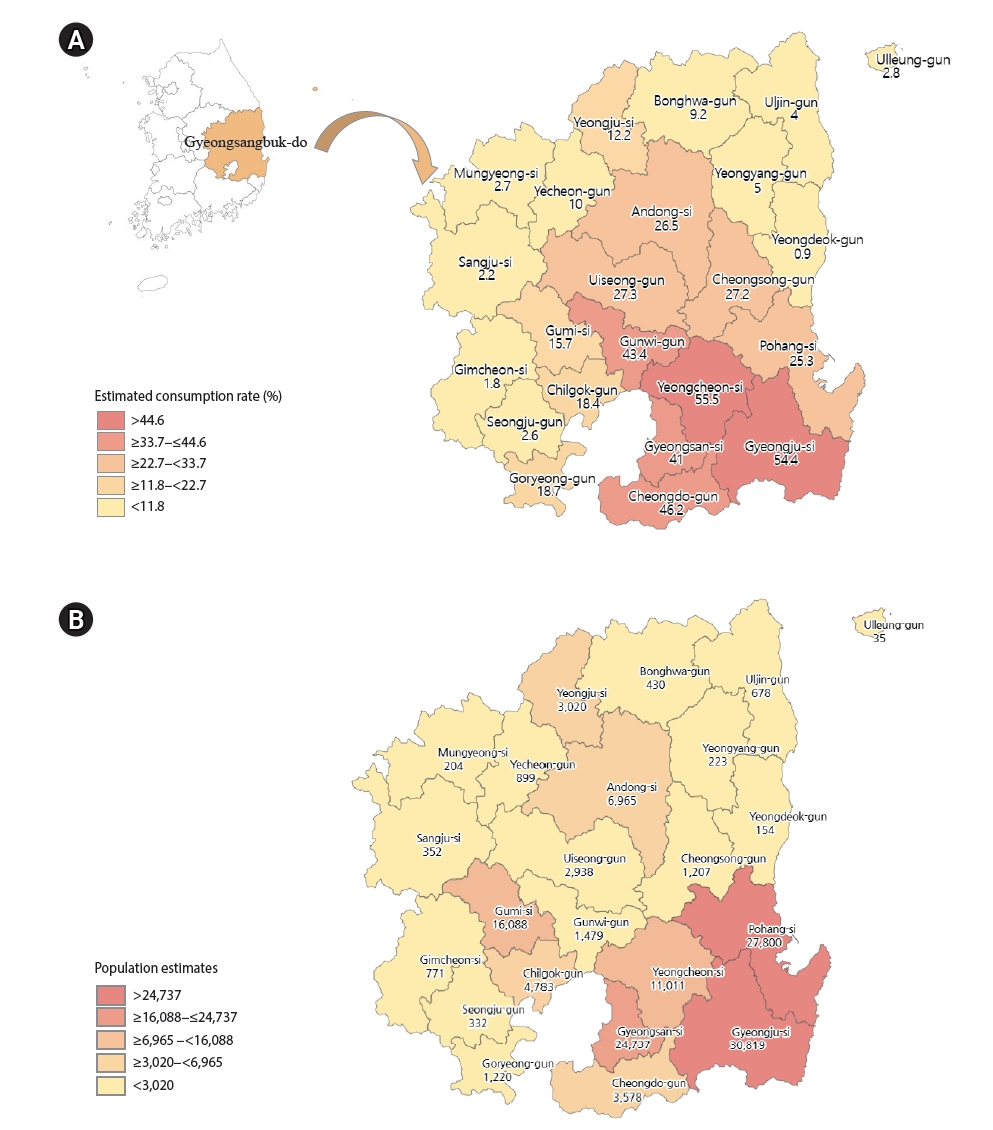

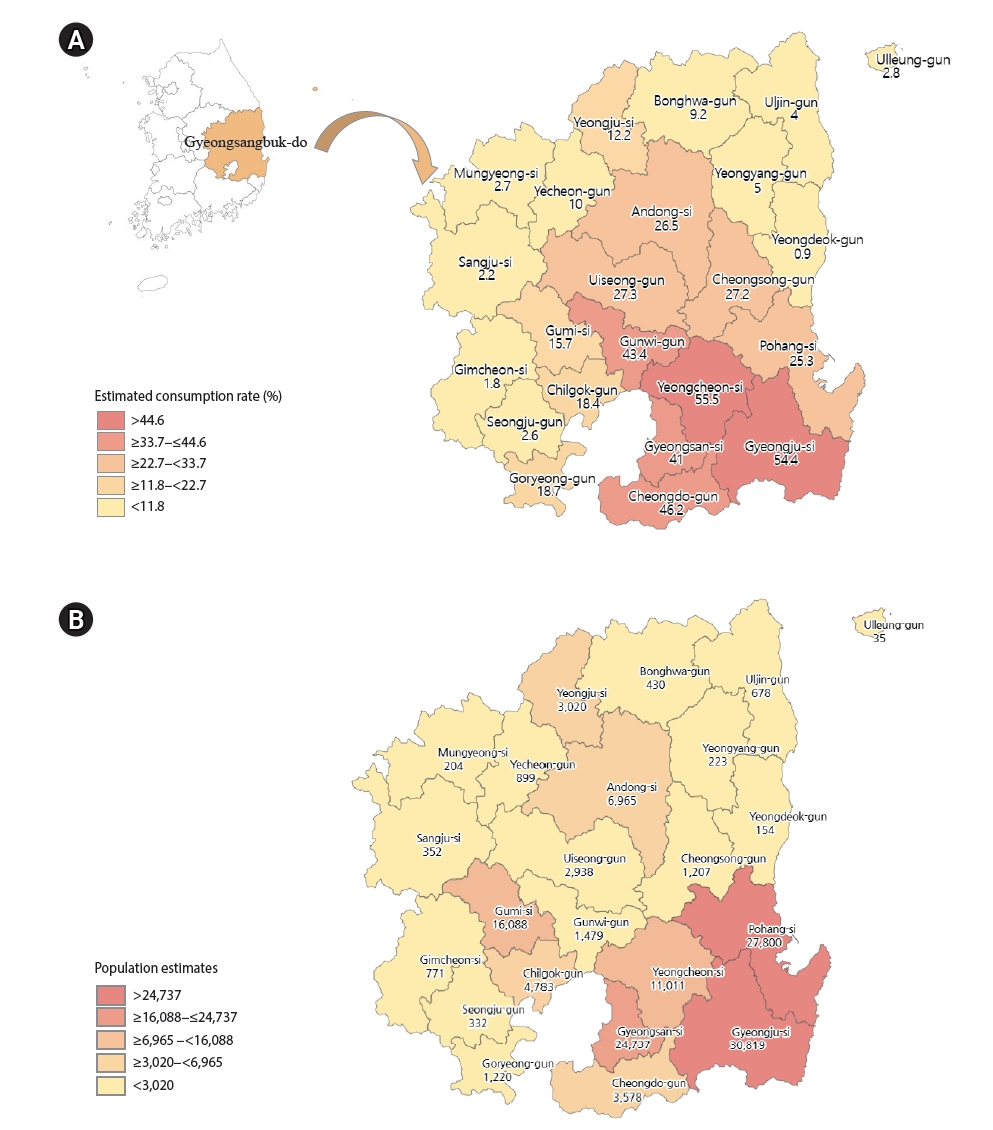

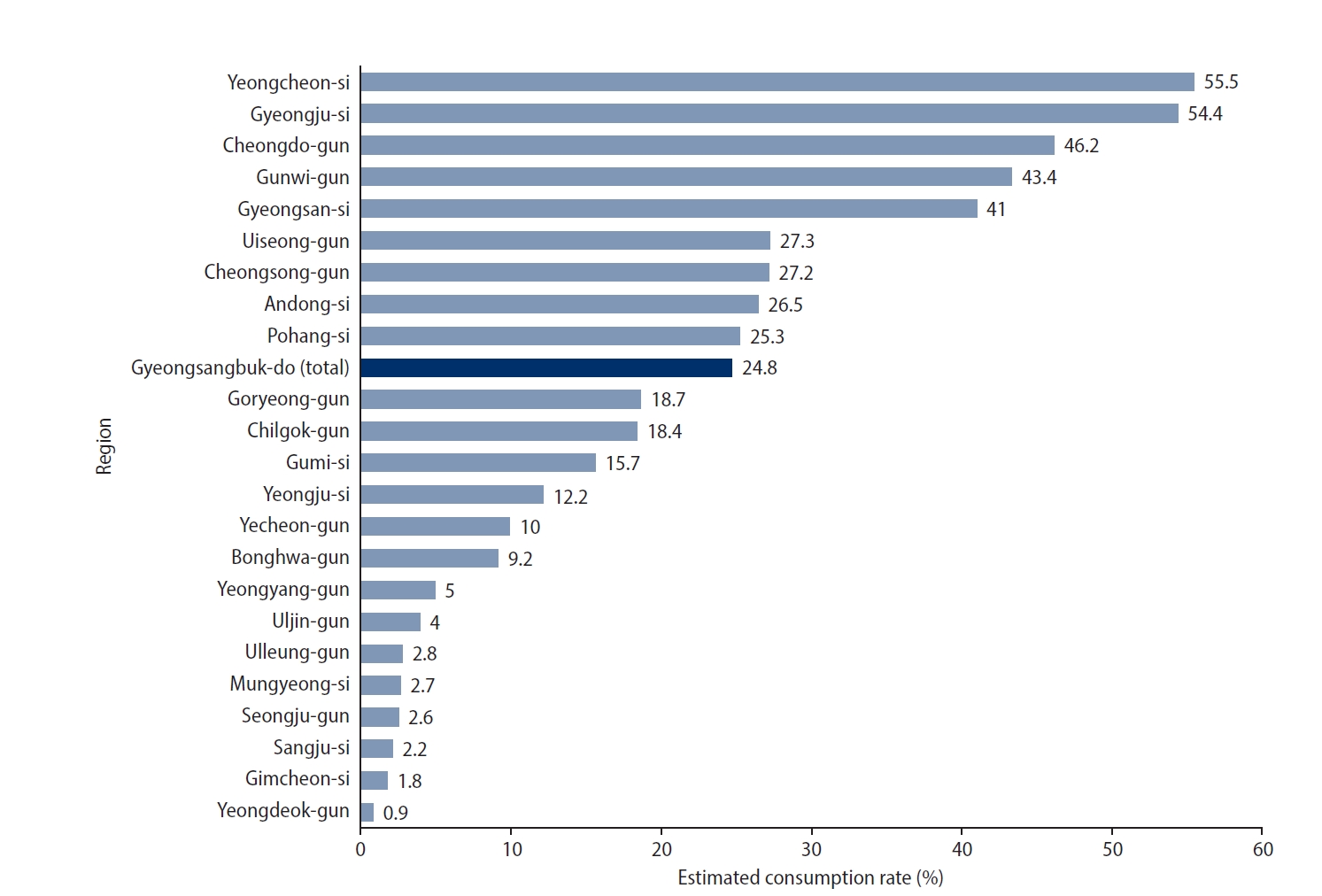

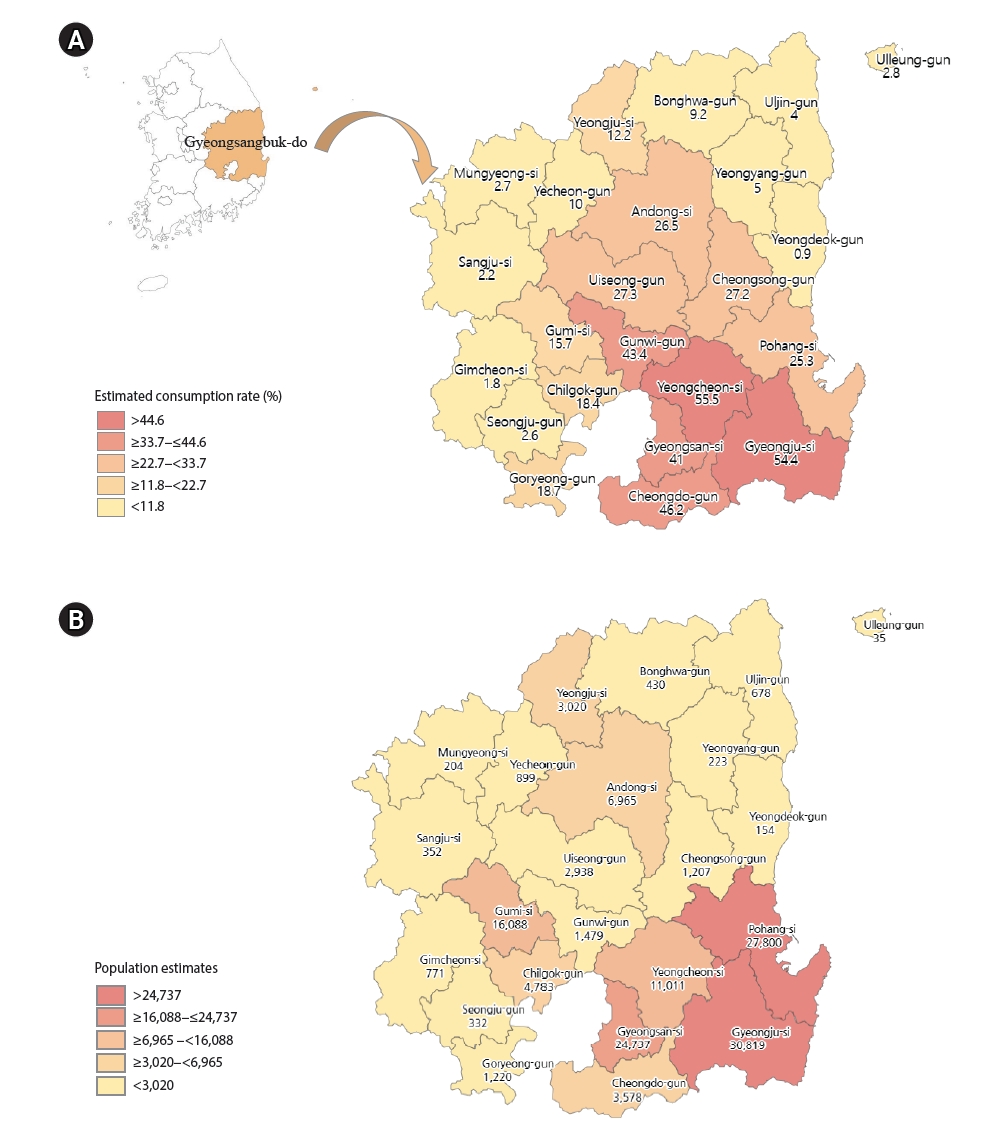

Calculation of shark meat consumption rate among young and middle-aged women in Gyeongsangbuk-do

The prevalence of shark meat consumption among young and middle-aged women in Gyeongsangbuk-do was 22.5%, and when calculated by region, the prevalences in Yeongcheon-si (54.6%), Gyeongju-si (50.0%), Cheongdo-gun (49.9%), Gunwi-gun (40.1%), Uisung-gun (38.4%), Gyeongsan-si (36.8%), and Cheongsong-gun (29.8%) were higher than the overall prevalence in Gyeongsangbuk-do (

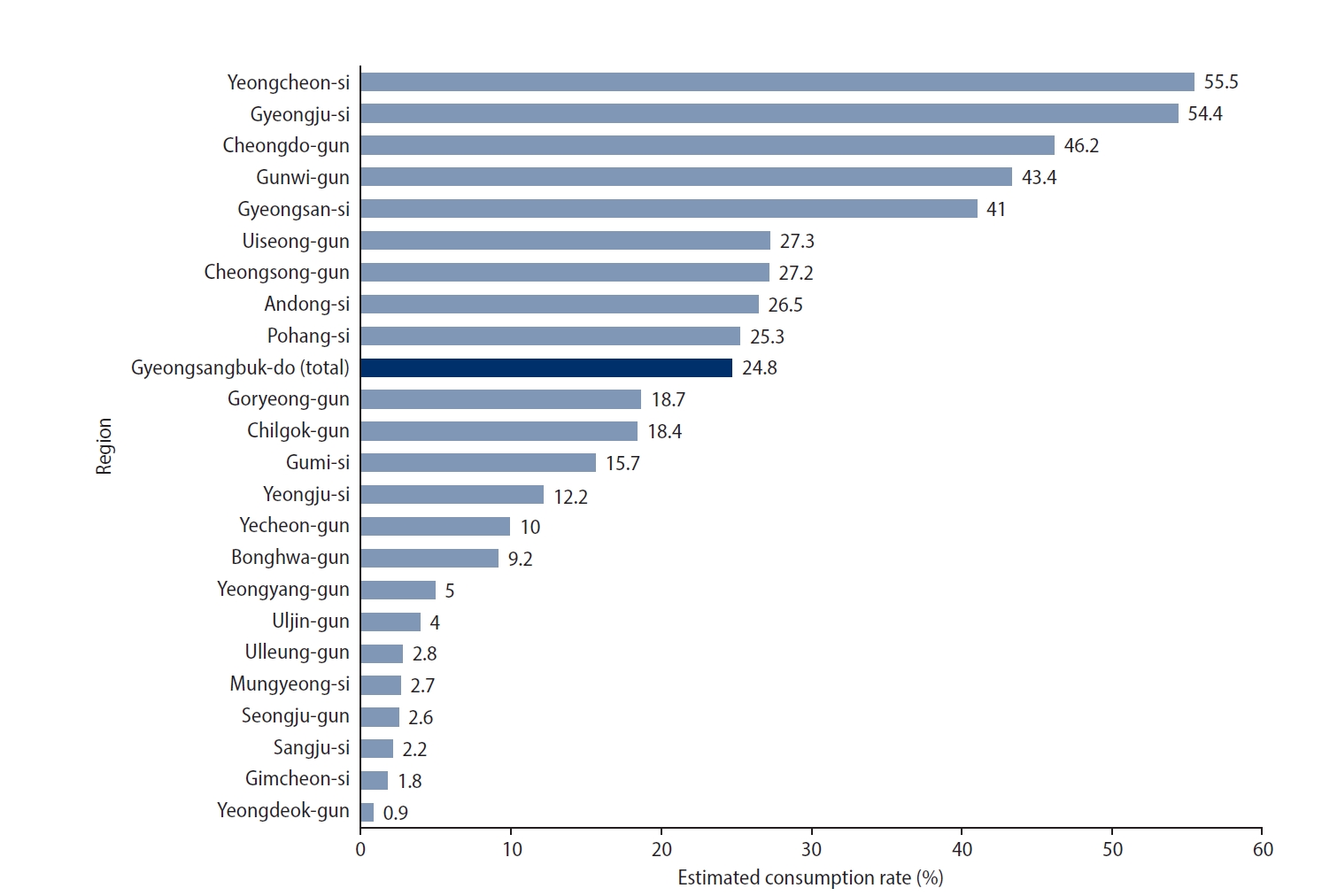

Fig. 1). The highest consumption rates were found in the central and southern regions of Gyeongsangbuk-do, with Yeongcheon having the highest (

Fig. 2A). The cities of Pohang and Gumi had lower consumption rates than Gyeongsangbuk-do had as a whole (22.0% and 13.1%, respectively). However, as these are densely populated areas, the parameter estimates exceeded 10,000 people (

Fig. 2B).

The prevalence of shark meat consumption among young and middle-aged women in Gyeongsangbuk-do was 18.6% (n = 14) of pregnant women, 23.1% (n = 49) of those who had given birth within the past year, and 26.5% (n = 23) of those who had breastfed within the past year.

Among women who had consumed shark meat (n = 3,568), the percentages of women reporting a serving size greater than or equal to the size of their entire palm were 7.1% (n = 61) of those of young and middle-aged women, 3.4% (n = 1) of those who were pregnant, 6.1% (n = 4) of those who had given birth in the past year, and 7.4% (n = 3) of those who had breastfed in the past year. As a result of population estimation, approximately 9,895 women (95% CI: 6,762–13,027) aged 19–55 in the overall population, and 255 women (95% CI: 139–371) who had breastfed within the past year, were found to have consumed shark meat in excess of the recommended intake.

Based on the estimated average annual intake of three times per year, the proportion of women who consumed more than this amount was 28.1% (n = 291) of all young and middle-aged women, 17.5% (n = 10) of those who had given birth in the past year, and 11.5% (n = 4) of those who had breastfed in the past year (

Table 2).

The number of servings were up to 156 per year (mean: 3.14; 95% CI: 2.92–3.35) among all young and middle-aged women, up to three per year (mean: 1.98; 95% CI: 1.60–2.37) among women who were pregnant, up to seven per year (mean: 2.59; 95% CI: 2.18–3.01) among women who had given birth within the past year; and up to seven per year (mean: 2.07; 95% CI: 1.89–2.25) among women who had breastfed within the past year. The mean annual total intake for all young and middle-aged women was 120 g, and the maximum was 7,800 g. The mean annual intake for pregnant women was 66 g, with a maximum of 200 g. For women who had given birth and breastfed within the past year, the mean annual intake was 107 g, with a maximum of 500 g (

Table 3).

Based on the mean value of mercury concentration in shark meat in Gyeongsangbuk-do (2.29 µg/g)

22, an estimation of 176 (n = 2 [95% CI: –133 to 486]) young and middle-aged women in the province exceeded the JECFA threshold (1.6 µg/kg/week)

23 and 20 (n = 1 [95% CI: –19 to 59]) exceeded the MFDS threshold (2.0 µg/kg/week).

24 Based on the maximum value of mercury concentration in shark meat in Gyeongsangbuk-do (8.93 µg/g)

22, it was estimated that 2,645 (n = 18 [95% CI: 1,053–4,237]) and 845 (n = 6 [95% CI: 46–1,645]) people exceeded the respective control standards. The estimated population figures of 2,645 and 845 are statistically significant, as their respective CIs do not include zero. Additionally, these estimates correspond to prevalence rates of 1.9% and 0.6%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

A comparison of shark meat consumption rates by region in Gyeongsangbuk-do showed that the central and southern regions of the province had higher shark meat consumption rates than the other regions. The south-central region of Gyeongsangbuk-do has a shark meat distribution network centered on Yeongcheon, while the Gyeongju and Andong regions focus on the tradition of turn-taking and rituals.

17,18 These characteristics may explain the difference in consumption rates between south-central region and other regions of the province.

Shark meat was also consumed by young and middle-aged women between the ages of 19–55. At around age 55, menopause typically begins, but the possibility of pregnancy exists in women prior to this age, albeit with a lower probability. Pregnancy in middle-aged women exposed to high levels of mercury, although the likelihood is low, carries greater risk due to the fetal toxicity of mercury in addition to the inherent risks of advanced maternal age.

The average number of servings was approximately three for all young and middle-aged women and about two for the subgroups. This is about the same as the number of festivals in the Republic of Korea (Lunar New Year and Chuseok), during which ancestral rites are usually held.

In this study, groups at higher risk for mercury exposure were those with a single intake of full-palm size or more and those whose weekly intake exceeds the PTWI established by regulatory authorities. Based on the number of respondents exceeding the single intake, population estimates revealed statistically significant results not only for the overall population of young and middle-aged women but also for women who had breastfed within the past year. Furthermore, when the mercury concentration in shark meat was 8.93 µg/g, the estimated population exceeding the PTWI was 845 (95% CI: 46–1,645).

To assess how well these estimates reflect the actual population, the number of women aged 19-55 and the actual number of births from January 1, 2017, to July 31, 2018, in the Gyeongsangbuk-do were investigated. These numbers were 615,260

25 and 28,176

26, respectively. The estimated population of women aged 19–55 in this study was 622,123 (95% CI: 601,875–642,371), with 37,110 women (95% CI: 31,815–42,405) having given birth within 1 year. When considering the number of births, discrepancies in the estimates were apparent. However, given that the survey period lasted three months and the total number of births during this time was 3,971,

26 the differences between the actual birth figures and the population estimates may be narrowed. Also, given that the community health survey sample used in this study was a reliable sample with stratification, proportioning, and systematic sampling, and considering that the timeframes for pregnancy, breastfeeding, and shark meat consumption were the same for 1 year, the likelihood that women in Gyeongsangbuk-do ingested mercury from shark meat during pregnancy or breastfeeding was not negligible.

The weekly mercury intake was calculated based on the mercury concentration in shark meat commercially available in the market.

22 The estimates of the population exceeding the PTWI were statistically significant only when the maximum mercury concentration, rather than the average concentration, was used in the analysis. This suggests a potential discrepancy between the estimates and reality. Nevertheless, the observation that the mercury concentration in commercially available shark meat exceeds regulatory standards indicates a need for more proactive advisory measures against shark meat consumption. It also suggests the necessity of updating control standards for mercury content in shark meat. The significance of the estimates lies not only in its alignment with reality, but also in its potential to serve as a reference for predicting how exposure levels to mercury may vary based on regulatory enforcement regarding mercury concentration in shark meat.

In Gyeongsangbuk-do, the average mercury concentrations in young and middle-aged women in areas with high consumption rates were as follows: Gyeongju 7.18 μg/L, Cheongsong 6.85 μg/L, Yeongdeok 6.33 μg/L, Pohang 6.43 μg/L, Yeongcheon 6.31 μg/L, Uisung 5.60 μg/L, Andong 5.55 μg/L, Gunwi 5.47 μg/L, Cheongdo 5.38 μg/L, and Gyeongsan 4.87 μg/L (Gyeongsangbuk-do overall 4 μg/L).

20 Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to examine the correlation between the mean mercury concentration in young and middle-aged women and the prevalence of shark meat consumption in each region of the study. The results showed that shark meat consumption rates were significantly positively correlated with mean mercury concentrations (

r = 0.394,

p = 0.01).

For shark meat consumption by pregnant women, the MFDS recommends a safe consumption limit of ≤100 g per week, based on a methylmercury concentration of 1 µg/g.

24 However, Heo et al.

22 measured mercury levels of 2.29 ± 1.77 µg/g (95% CI: 0.06–8.93 µg/g) in shark meat distributed in Gyeongbuk Province. The actual average and maximum values were higher than the MFDS standards. Therefore, the risk of consuming shark meat may be much higher than recommended.

Methylmercury is completely absorbed by the digestive system and distributed throughout the body within 30 hours.

8 Therefore, even a single intake is not without risk. Considering that eating 1 g of shark meat increases blood mercury levels by 0.02 μg/L,

21 consuming shark meat according to national and international control standards (100 g/day)

24,27 can increase blood mercury levels by 2 μg/L. The reference value for maternal blood mercury is 3.5 μg/L according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention standards.

27-30 Therefore, to keep the blood mercury level below the reference value after consuming 100 g of shark meat, the baseline blood mercury level should be 1.5 μg/L. However, the average blood mercury level for women in Republic of Korea is 3.11 µg/L (95% CI: 2.36–2.65 µg/L),

31 which means that there is a possibility of childbearing women exceeding the reference value after consuming 100 g of shark meat.

Our results can be used as a background for region-specific communication on the risks of shark meat consumption. The analysis of consumption characteristics suggests a strong need for more active advisories and monitoring of shark meat consumption in young and middle-aged women. However, limitations of this study include the fact that the exact blood mercury levels of the study subjects were unknown and that other foods that may affect blood mercury levels were not examined. In addition, recall bias in questionnaire responses to items about shark meat consumption characteristics might have been present. This was especially because the intake was based on hand size, subject to individual variation, rather than using models for 25, 50, or 100 g of shark meat. Therefore, the risk of mercury exposure from shark meat might not be as accurate when calculated using the PTWI or estimated blood mercury levels. In addition, neurodevelopmental symptoms in infants and children born after prenatal mercury exposure were not available for subjects estimated to have been exposed to mercury above the risk level, and this needs to be included in future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights the substantial risks associated with shark meat consumption among young and middle-aged women in the Gyeongsangbuk-do. It is estimated that 7.1% exceed the single intake limit, while up to 1.9% exceed the JECFA’s PTWI and up to 0.6% exceed the MFDS’s PTWI, indicating a level of risk that warrants monitoring and guidance. Community-level interventions are necessary to raise awareness of the hazards of shark meat consumption in this vulnerable population. Continuous monitoring of methylmercury levels in shark meat is essential to ensure public health and safety. Our findings underscore the urgent need for more stringent advisory measures and updated standards to regulate mercury levels in shark meat.

Abbreviations

Joint Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization Expert Committee on Food Additives

Ministry of Food and Drug Safety

provisional tolerable weekly intake

NOTES

-

Funding

This work was supported by the 2023 Yeungnam University Research Grant.

-

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Sakong J. Data curation: Son S. Formal analysis: Son S, Seong J. Investigation: Sakong J. Resources: Sakong J, Son S. Methodology: Park C, Baek K. Software: Seong J. Validation: Park C, Baek K. Visualization: Son S, Seong J. Supervision: Sakong J. Project administration: Park C, Baek K. Funding acquisition: Sakong J. Writing - original draft: Son S, Baek K. Writing - review & editing: Sakong J, Park C, Seong J.

-

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Dong-Wook Lee, Inha University Hospital, and Dr. Young-Seoub Hong, Donga University Hospital, for their technical assistance for this study.

Fig. 1.Estimated shark meat consumption rate (%) among young and middle-aged women in Gyeongsangbuk-do. Consumption rate (%) is defined as the proportion of respondents who had eaten shark meat in the past year among all young and middle-aged women.

Fig. 2.(A) Geographical distribution of estimated consumption rate (%) in Gyeongsangbuk-do. Consumption rate (%) is defined as the proportion of respondents who had eaten shark meat in the past year among all young and middle-aged women, and was presented with the degree of darkness on each region. (B) Geographic distribution of population estimates of shark meat consumption. Population estimates were calculated using complex sampling design, and were presented with the degree of darkness on each region.

Table 1.General characteristics of the study subjects

|

Characteristic |

No.a

|

%b (SEc) |

|

|

Female age group |

|

|

|

|

Age 19–55 years |

4,484 |

44.8 (0.7) |

|

|

Age > 55 years |

7,881 |

55.2 (0.7) |

|

|

Total |

12,365 |

100 |

|

|

Pregnancy status |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

69 |

1.9 (0.3) |

|

|

No |

4,415 |

98.1 (0.3) |

|

|

Total |

4,484 |

100 |

|

|

Experience of delivery in the past year |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

231 |

6.0 (0.4) |

|

|

No |

4,253 |

94.0 (0.4) |

|

|

Total |

4,484 |

100 |

|

|

Experience of breastfeedingd in the past 1 year |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

82 |

35.1 (3.6) |

|

|

No |

149 |

64.9 (3.6) |

|

|

Total |

231 |

100 |

|

|

Age (years) |

|

|

|

|

19–29 |

770 |

23.6 (0.8) |

|

|

30–39 |

1,043 |

24.5 (0.9) |

|

|

40–49 |

1,492 |

31.1 (0.9) |

|

|

50–55 |

1,179 |

20.8 (0.7) |

|

|

Total |

4,484 |

100 |

|

Table 2.Characteristics of shark meat consumption in young and middle-aged women

|

Young and middle-aged women

|

Pregnant

|

Delivery within 1 year

|

Breastfeeding within 1 year

|

|

na

|

Nb

|

95% CIc

|

%d (SEe) |

n |

N |

95% CI |

% (SE) |

n |

N |

95% CI |

% (SE) |

n |

N |

95% CI |

% (SE) |

|

Annual consumption experience |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

916 |

139,733 |

128,776 to 150,690 |

22.5 (0.8) |

14 |

2,230 |

1,013 to 3,446 |

18.6 (4.9) |

49 |

8,582 |

5,947 to 11,216 |

23.1 (3.3) |

23 |

3,457 |

1,890 to 5,023 |

26.5 (5.6) |

|

No |

3,568 |

482,390 |

464,192 to 500,588 |

77.5 (0.8) |

55 |

9,753 |

6,605 to 12,900 |

81.4 (4.9) |

182 |

28,528 |

23,723 to 33,332 |

76.9 (3.3) |

59 |

9,564 |

6,680 to 12,448 |

73.5 (5.6) |

|

Quantity per serving |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two fingers or smaller |

620 |

92,629 |

83,859 to 101,400 |

66.3 (1.9) |

11 |

1,716 |

678 to 2,755 |

77 (12.4) |

27 |

5,215 |

3,090 to 7,339 |

60.8 (7.6) |

9 |

1,523 |

332 to 2714 |

44.1 (12.2) |

|

Half-palm size |

235 |

37,207 |

31,578 to 42,836 |

26.6 (1.8) |

2 |

437 |

–177 to 1,053 |

19.6 (12.2) |

18 |

2,846 |

1,541 to 4,152 |

33.2 (6.5) |

11 |

1,678 |

627 to 2,728 |

48.5 (12.4) |

|

Full-palm size or more |

61 |

9,895 |

6,762 to 13,027 |

7.1 (1.1) |

1 |

75 |

–72 to 223 |

3.4 (3.4) |

4 |

520 |

–11 to 1,051 |

6.1 (2.9) |

3 |

255 |

139 to 371 |

7.4 (2.3) |

|

Annual consumption frequency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤3 times/year |

625 |

100,487 |

90,391 to 110,577 |

71.9 (1.9) |

14 |

2,230 |

1,014 to 3,446 |

100 (0) |

39 |

7,081 |

4,510 to 9,652 |

82.5 (5.9) |

19 |

3,059 |

1,484 to 4,635 |

88.5 (6.4) |

|

≥4 times/year |

291 |

39,245 |

33,345 to 45,145 |

28.1 (1.9) |

|

|

|

|

10 |

1,500 |

451 to 2,550 |

17.5 (5.9) |

4 |

397 |

–48 to 843 |

11.5 (6.4) |

Table 3.Mean and maximum annual consumption in young and middle-aged women

|

Young and middle-aged women

|

Pregnant

|

Delivery within 1 year

|

Breastfeeding within 1 year

|

|

Mean |

95% CI |

Maximum |

Mean |

95% CI |

Maximum |

Mean |

95% CI |

Maximum |

Mean |

95% CI |

Maximum |

|

Annual consumption frequency (times/year) |

3.14 |

2.92–3.35 |

156 |

2 |

1.60–2.37 |

3 |

2.59 |

2.18–3.01 |

7 |

2.07 |

1.89–2.25 |

7 |

|

Annual consumption quantity (g/year) |

120.06 |

110.63–129.49 |

7800 |

67 |

43.30–89.78 |

200 |

107.9 |

87.16–128.53 |

500 |

108 |

89.46–126.35 |

500 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Selin NE. Global biogeochemical cycling of mercury: a review. Annu Rev Environ Resour 2009;34:43–63.Article

- 2. Hamdy MK, Noyes OR. Formation of methyl mercury by bacteria. Appl Microbiol 1975;30(3):424–32.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 3. Eto K. Minamata disease. Neuropathology 2000;20 Suppl:S14–9.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Matsumoto H, Koya G, Takeuchi T. Fetal minamata disease: a neuropathological study of two cases of intrauterine intoxication by a methyl mercury compound. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1965;24(4):563–74.PubMed

- 5. Harada M. Congenital Minamata disease: intrauterine methylmercury poisoning. Teratology 1978;18(2):285–8.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Cohen JT, Bellinger DC, Shaywitz BA. A quantitative analysis of prenatal methyl mercury exposure and cognitive development. Am J Prev Med 2005;29(4):353–65.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Axelrad DA, Bellinger DC, Ryan LM, Woodruff TJ. Dose-response relationship of prenatal mercury exposure and IQ: an integrative analysis of epidemiologic data. Environ Health Perspect 2007;115(4):609–15.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Mercury. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 2022.

- 9. Lederman SA, Jones RL, Caldwell KL, Rauh V, Sheets SE, Tang D, et al. Relation between cord blood mercury levels and early child development in a World Trade Center cohort. Environ Health Perspect 2008;116(8):1085–91.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Bjornberg KA, Vahter M, Berglund B, Niklasson B, Blennow M, Sandborgh-Englund G. Transport of methylmercury and inorganic mercury to the fetus and breast-fed infant. Environ Health Perspect 2005;113(10):1381–5.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Jedrychowski W, Perera F, Jankowski J, Rauh V, Flak E, Caldwell KL, et al. Fish consumption in pregnancy, cord blood mercury level and cognitive and psychomotor development of infants followed over the first three years of life: Krakow epidemiologic study. Environ Int 2007;33(8):1057–62.PubMed

- 12. Gilbert SG, Grant-Webster KS. Neurobehavioral effects of developmental methylmercury exposure. Environ Health Perspect 1995;103 Suppl 6(Suppl 6):135–42.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Kim Y, Ha EH, Park H, Ha M, Kim Y, Hong YC, et al. Prenatal mercury exposure, fish intake and neurocognitive development during first three years of life: prospective cohort mothers and Children's environmental health (MOCEH) study. Sci Total Environ 2018;615:1192–8.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Goyanna FA, Fernandes MB, Silva GB, Lacerda LD. Mercury in oceanic upper trophic level sharks and bony fishes: a systematic review. Environ Pollut 2023;318:120821.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Ye S, Shin J, Lee J, Jung EM, Lee J, Yun E, et al. Systematic review of heavy metal concentrations in fish and shellfish in Korea. Ewha Med J 2018;41(1):1–7.ArticlePDF

- 16. Dent F, Clarke S. State of the Global Market for Shark Products. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2015.

- 17. The Federation of Korean Cultural Centers. Andong Dombaegi skewers, a dish that couldn't be left out of the rituals. https://ncms.nculture.org/food/story/1917. Updated 2024. Accessed Februry 20, 2024

- 18. The Academy of Korean Studies. Where did the "Dombaegi" in Yeongcheon big market come from? http://www.grandculture.net/yeongcheon/toc/GC05100010. Updated 2024. Accessed Februry 20, 2024

- 19. Cho S, Jacobs DR Jr, Park K. Population correlates of circulating mercury levels in Korean adults: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey IV. BMC Public Health 2014;14:527.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 20. National Institute of Environmental Research. Assessment of Mercury Exposure and Health in Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk-do (I). Incheon, Korea: National Institute of Environmental Research; 2011.

- 21. Baek K, Park C, Sakong J. Increase of blood mercury level with shark meat consumption: a repeated-measures study before and after Chuseok, Korean holiday. Chemosphere 2023;344:140317.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Heo HC, Lim YH, Byun YS, Sakong J. Mercury concentration in shark meat from traditional markets of Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea. Ann Occup Environ Med 2020;32:e3.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 23. Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA). Methylmercury. https://apps.who.int/food-additives-contaminants-jecfa-database/Home/Chemical/3083. Updated 2007. Accessed February 12, 2024

- 24. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Tips for Safe Fish Consumption in Pregnant Women. Cheongju, Korea: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety; 2015.

- 25. Ministry of the Interior and Safety. Population by age group by administrative district. https://jumin.mois.go.kr/ageStatMonth.do. Updated 2024. Accessed September 26, 2024

- 26. Ministry of the Interior and Safety. Birth registration by administrative district based on resident registration. https://jumin.mois.go.kr/etcStatBirth.do. Updated 2024. Accessed August 10, 2024

- 27. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Technical Information on Development of FDA/EPA Advice about Eating Fish for Thos Who Might Become or Are Pregnant or Breastfeeding and Children Ages 1-11 Years. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2022.

- 28. United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Resources for mercury science and research. https://www.epa.gov/mercury/resources-mercury-science-and-research. Updated 2023. Accessed February 2, 2024

- 29. Wickliffe JK, Lichtveld MY, Zijlmans CW, MacDonald-Ottevanger S, Shafer M, Dahman C, et al. Exposure to total and methylmercury among pregnant women in Suriname: sources and public health implications. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2021;31(1):117–25.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 30. Mahaffey KR, Clickner RP, Bodurow CC. Blood organic mercury and dietary mercury intake: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 and 2000. Environ Health Perspect 2004;112(5):562–70.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. National Institute of Environmental Research (NIER). Korean Environmental Health Survey: the fourth stage (2018-2020). https://stat.me.go.kr/portal/stat/easyStatPage.do?cateId=106H_01_008004. Updated 2022. Accessed December 29, 2023

, Junmin Seong1

, Junmin Seong1 , Chulyong Park1,2

, Chulyong Park1,2 , Kiook Baek3

, Kiook Baek3 , Joon Sakong1,2,*

, Joon Sakong1,2,*

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite