Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Occup Environ Med > Volume 30; 2018 > Article

- Research Article Mental disorders among workers in the healthcare industry: 2014 national health insurance data

- Min-Seok Kim1, Taeshik Kim1, Dongwook Lee1, Ji-hoo Yook1, Yun-Chul Hong1, Seung-Yup Lee2, Jin-Ha Yoon3, Mo-Yeol Kang4

-

Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2018;30:31.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40557-018-0244-x

Published online: May 3, 2018

1Department of Preventive Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 103 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080 Republic of Korea

2Department of Psychiatry, Uijeongbu St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, 271 Cheonbo-ro, Uijeongbu, Gyeonggi-do Republic of Korea

3Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, 50-1 Yonsei-ro, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03722 Republic of Korea

4Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Medicine Korea, 222, Banpo-daero, Seocho-gu, Seoul 06591 Republic of Korea

© The Author(s). 2018

Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Abstract

-

Background Numerous studies have shown that healthcare professionals are exposed to psychological distress. However, since most of these studies assessed psychological distress using self-reporting questionnaires, the magnitude of the problem is largely unknown. We evaluated the risks of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, and any psychiatric disorders in workers in healthcare industry using Korea National Health Insurance (NHI) claims data from 2014, which are based on actual diagnoses instead of self-evaluation.

-

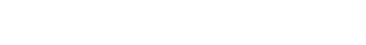

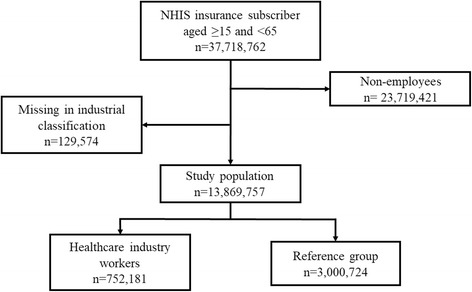

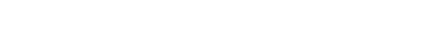

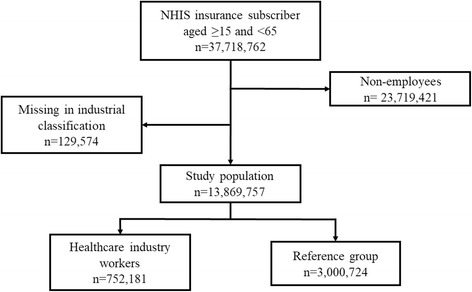

Methods We used Korea 2014 NHI claims data and classified employees as workers in the healthcare industry, based on companies in the NHI database that were registered with hospitals, clinics, public healthcare, and other medical services. To estimate the standardized prevalence of the selected mental health disorders, we calculated the prevalence of diseases in each age group and sex using the age distribution of the Korea population. To compare the risk of selected mental disorders among workers in the healthcare industry with those in other industries, we considered age, sex, and income quartile characteristics and conducted propensity scored matching.

-

Results In the matching study, workers in healthcare industry had higher odds ratios for mood disorders (1.13, 95% CI: 1.11–1.15), anxiety disorders (1.15, 95% CI: 1.13–1.17), sleep disorders (2.21, 95% CI: 2.18–2.24), and any psychiatric disorders (1.44, 95% CI: 1.43–1.46) than the reference group did. Among workers in healthcare industry, females had higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders than males, but the odds ratios for psychiatric disorders, compared to the reference group, were higher in male workers in healthcare industry than in females.

-

Conclusions The prevalence of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, and all psychiatric disorders for workers in the healthcare industry was higher than that of other Korean workers. The strikingly high prevalence of sleep disorders could be related to the frequent night-shifts in these professions. The high prevalence of mental health problems among workers in healthcare industry is alarming and requires prompt action to protect the health of the “protectors.”

Background

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

- 1.

- 2.

- 3. Hensing G, Spak F. Psychiatric disorders as a factor in sick-leave due to other diagnoses. A general population-based study. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172:250–256. 10.1192/bjp.172.3.250. 9614475.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Nystuen P, Hagen KB, Herrin J. Mental health problems as a cause of long-term sick leave in the Norwegian workforce. Scand J Soc Med 2001;29:175–182.ArticlePDF

- 5. Michie S, Williams S. Reducing work related psychological ill health and sickness absence: a systematic literature review. Occup Environ Med 2003;60:3–9. 10.1136/oem.60.1.3. 12499449.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Suzuki K, Ohida T, Kaneita Y, Yokoyama E, Miyake T, Harano S, et al. Mental health status, shift work, and occupational accidents among hospital nurses in Japan. J Occup Health 2004;46:448–454. 10.1539/joh.46.448. 15613767.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2010;251:995–1000. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. 19934755.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Schwenk TL, Gorenflo DW, Leja LM. A survey on the impact of being depressed on the professional status and mental health care of physicians. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 2008;69:617–620. 10.4088/JCP.v69n0414. 18426258.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Lee Y, Kim K. Experiences of nurse turnover. J Korean Acad Nurs 2008;38:248–257. 10.4040/jkan.2008.38.2.248.Article

- 10. Leiter MP, Maslach C. Nurse turnover: the mediating role of burnout. J Nurs Manag 2009;17:331–339. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01004.x. 19426369.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Duffield CM, Roche MA, Homer C, Buchan J, Dimitrelis S. A comparative review of nurse turnover rates and costs across countries. J Adv Nurs 2014;70(12):2703. 10.1111/jan.12483. 25052582.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 12. O’Brien-Pallas L, Griffin P, Shamian J, Buchan J, Duffield C, Hughes F, et al. The impact of nurse turnover on patient, nurse, and system outcomes: a pilot study and focus for a multicenter international study. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 2006;7:169–179. 10.1177/1527154406291936.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 13. Misra-Hebert AD, Kay R, Stoller JK. A review of physician turnover: rates, causes, and consequences. Am J Med Qual 2004;19:56–66. 10.1177/106286060401900203. 15115276.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 14. Deckard G, Meterko M, Field D. Physician burnout: an examination of personal, professional, and organizational relationships. Med Care 1994;32(7):745–754. 10.1097/00005650-199407000-00007. 8028408.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Felton JS. Burnout as a clinical entity—its importance in health care workers. Occup Med 1998;48:237–250. 10.1093/occmed/48.4.237.Article

- 16. Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:1017–1022. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00227-4. 9089922.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Ruotsalainen J, Serra C, Marine A, Verbeek J. Systematic review of interventions for reducing occupational stress in health care workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 2008;34:169–178. 10.5271/sjweh.1240. 18728906.ArticlePubMed

- 18.

- 19. Owens JA. Sleep loss and fatigue in healthcare professionals. The Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing 2007;21:92–100. 10.1097/01.JPN.0000270624.64584.9d. 17505227.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Gimeno D, Vahtera J, Elovainio M, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Long working hours and sleep disturbances: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Sleep 2009;32:737–745. 10.1093/sleep/32.6.737. 19544749.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Wall TD, Bolden RI, Borrill CS, Carter AJ, Golya DA, Hardy GE, et al. Minor psychiatric disorder in NHS trust staff: occupational and gender differences. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:519–523. 10.1192/bjp.171.6.519. 9519089.ArticlePubMed

- 22. McNeely E. The consequences of job stress for nurses’ health: time for a check-up. Nurs Outlook 2005;53:291–299. 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.10.001. 16360700.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Embriaco N, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Pochard F, Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Curr Opin Crit Care 2007;13:482–488. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282efd28a. 17762223.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Hegney DG, Craigie M, Hemsworth D, Osseiran-Moisson R, Aoun S, Francis K, et al. Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, anxiety, depression and stress in registered nurses in Australia: study 1 results. J Nurs Manag 2014;22:506–518. 10.1111/jonm.12160. 24175955.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 25. Kim K, Lee S, Choi YH. Relationship between occupational stress and depressive mood among interns and residents in a tertiary hospital, Seoul, Korea. Clinical and Experimental Emergency Medicine 2015;2:117–122. 10.15441/ceem.15.002. 27752582.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 26. Tomioka K, Morita N, Saeki K, Okamoto N, Kurumatani N. Working hours, occupational stress and depression among physicians. Occup Med 2011;61:163–170. 10.1093/occmed/kqr004.Article

- 27. Ahola K, Honkonen T, Isometsä E, Kalimo R, Nykyri E, Aromaa A, et al. The relationship between job-related burnout and depressive disorders—results from the Finnish health 2000 study. J Affect Disord 2005;88:55–62. 10.1016/j.jad.2005.06.004. 16038984.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG. Social class and minor psychiatric disorder in British civil servants: a validated screening survey using the general health questionnaire. Psychol Med 1992;22:739. 10.1017/S0033291700038186. 1410098.ArticlePubMed

- 29. http://kosis.kr.

- 30. Austin PC, Grootendorst P, Anderson GM. A comparison of the ability of different propensity score models to balance measured variables between treated and untreated subjects: a Monte Carlo study. Stat Med 2007;26:734–753. 10.1002/sim.2580. 16708349.ArticlePubMed

- 31. Sohn J-W, Kim B-G, Kim S-H, Han C. Mental health of healthcare workers who experience Needlestick and sharps injuries. J Occup Health 2006;48:474–479. 10.1539/joh.48.474. 17179640.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 32. Gao Y-Q, Pan B-C, Sun W, Wu H, Wang J-N, Wang L. Depressive symptoms among Chinese nurses: prevalence and the associated factors. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:1166–1175. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05832.x. 21950775.ArticlePubMed

- 33. Wang J-N, Sun W, Chi T-S, Wu H, Wang L. Prevalence and associated factors of depressive symptoms among Chinese doctors: a cross-sectional survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2010;83:905–911. 10.1007/s00420-010-0508-4. 20112108.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 34.

- 35. Mealer ML, Shelton A, Berg B, Rothbaum B, Moss M. Increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in critical care nurses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:693–697. 10.1164/rccm.200606-735OC. 17185650.ArticlePubMed

- 36. Mealer M, Burnham EL, Goode CJ, Rothbaum B, Moss M. The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depression and Anxiety 2009;26:1118–1126. 10.1002/da.20631. 19918928.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 37.

- 38. Leiter MP, Harvie PL. Burnout among mental health workers: a review and a research agenda. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1996;42:90–101. 10.1177/002076409604200203. 8811393.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 39. Gómez-Urquiza JL, De la Fuente-Solana EI, Albendín-García L, Vargas-Pecino C, Ortega-Campos EM, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome in Emergency Nurses: A Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Nurse 2017;37:e1–e9. 10.4037/ccn2017508. 28966203.Article

- 40. Soler JK, Yaman H, Esteva M, Dobbs F, Asenova RS, Katic M, et al. Burnout in European family doctors: the EGPRN study. Fam Pract 2008;25:245–265. 10.1093/fampra/cmn038. 18622012.ArticlePubMed

- 41. Blanchard P, Truchot D, Albiges-Sauvin L, Dewas S, Pointreau Y, Rodrigues M, et al. Prevalence and causes of burnout amongst oncology residents: a comprehensive nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer 2010;46(15):2708. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.014. 20627537.ArticlePubMed

- 42. Maslach C, Jackson SE. Leiter MP Maslach burnout inventory manual. 1996, Palo alto. California: Consulting Psychological Press, Inc.

- 43. Ahola K, Honkonen T, Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Isometsä E, Aromaa A, et al. Contribution of burnout to the association between job strain and depression: the health 2000 study. J Occup Environ Med 2006;48:1023–1030. 10.1097/01.jom.0000237437.84513.92. 17033502.ArticlePubMed

- 44.

- 45. Cooper CL, Swanson N. Workplace violence in the health sector. 2002, State of the art Geneva: Organización Internacional de Trabajo, Organización Mundial de la Salud, Consejo Internacional de Enfermeras Internacional de Servicios Públicos.

- 46. Jeung D-Y, Lee H-O, Chung WG, Yoon J-H, Koh SB, Back C-Y, et al. Association of Emotional Labor, self-efficacy, and type a personality with burnout in Korean dental hygienists. J Korean Med Sci 2017;32:1423. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.9.1423. 28776336.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 47. Yoon J-H, Kang M-Y, Jeung D, Chang S-J. Suppressing emotion and engaging with complaining customers at work related to experience of depression and anxiety symptoms: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Ind Health. 2017;55:265–74. 10.2486/indhealth.2016-0069. 28216516.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 48. Wright KP, Bogan RK, Wyatt JK. Shift work and the assessment and management of shift work disorder (SWD). Sleep Med Rev 2013;17:41–54. 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.02.002. 22560640.ArticlePubMed

- 49. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Henderson S. Attitudes towards people with a mental disorder: a survey of the Australian public and health professionals. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 1999;33:77–83. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00513.x. 10197888.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 50. Björkman T, Angelman T, Jönsson M. Attitudes towards people with mental illness: a cross-sectional study among nursing staff in psychiatric and somatic care. Scand J Caring Sci 2008;22:170–177. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00509.x. 18489686.ArticlePubMed

- 51. Korea Health Industry Development Institute. Healthcare workforce - Number of medical personnel in hospital [Internet]. 2016.

REFERENCES

Notes

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- Internal Communication and Dissemination Strategies During Magnet Implementation in German Hospitals: A Qualitative Study

Joan Kleine, Carolin Gurisch, Julia Köppen, Reinhard Busse, Lisa Smeds Alenius, Paolo C. Colet

Journal of Nursing Management.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - Mapping research trajectories of platform working and employee well-being: a bibliometric cartography

Shefali Sharma, Amit Mittal, Seema Seema

Kybernetes.2026; : 1. CrossRef - Does leading through algorithmic management impact the workers’ well-being: a systematic literature review and research agenda

Shefali Sharma, Amit Mittal, Seema Seema

Leadership & Organization Development Journal.2026; : 1. CrossRef - Craving under pressure: the interplay between hedonic hunger, mental health, and ultra-processed food consumption in shift-workers

Elif Akin, Hatice Merve Bayram, Arda Ozturkcan

Frontiers in Public Health.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - Determinants of anxiety and depression and their association with coping strategies in health professionals in war and conflict-afflicted areas

Maisa Nabulsi, Muna Ahmead, Nuha El Sharif

Frontiers in Psychiatry.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program on Job Satisfaction and Psychological Distress of Care Workers for Older Adults

Nurgül Karakurt, Meltem Oral

Workplace Health & Safety.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - Generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder among healthcare professionals in Mbarara city, southwestern Uganda: the relationship with professional quality of life and resilience

Joan Abaatyo, Alain Favina, Margaret Twine, Dan Lutasingwa, Rosemary Ricciardelli, Godfrey Zari Rukundo

BMC Public Health.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - The Impact of Self-Compassion on Enhancing the Professional Quality of Life for Healthcare Workers

Eulji Jung, Young-Eun Jung

Journal of Korean Medical Science.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Factors associated with depression and anxiety among mental healthcare practitioners

Cheval Murugas, Carla Kotzé

Journal of the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - A Reliability Generalization Meta-Analysis of Scores on the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) Scale Across Sample Characteristics

A. Stephen Lenz, Carla Smith, Amber Meegan

Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development.2024; 57(4): 403. CrossRef - Assessment of the importance of sleep quality and the effects of deprivation on Sudanese healthcare professionals amidst conflict in Sudan

Mohammed Hammad Jaber Amin, Musab Awadalla Mohamed Elhassan Elmahi, Gasm Alseed Abdelmonim Gasm Alseed Fadlalmoula, Jaber Hammad Jaber Amin, Noon Hatim Khalid Alrabee, Mohammed Haydar Awad, Zuhal Yahya Mohamed Omer, Nuha Tayseer Ibrahim Abu Dayyeh, Nada A

Sleep Science and Practice.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Prevalence and predictors of depression and anxiety among workers at two points of entry in Botswana during the COVID-19 pandemic

Keatlaretse Siamisang, Naledi Mokgethi, Leungo Audrey Nthibo, Matshwenyego Boitshwarelo, Onalethata Lesetedi

The Pan African Medical Journal.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Laying the foundations for implementing Magnet principles in hospitals in Europe: A qualitative analysis

Ingrid Svensson, Jackie Bridges, Jaimie Ellis, Noeleen Brady, Simon Dello, Jonathan Hooft, Joan Kleine, Dorothea Kohnen, Elaine Lehane, Rikard Lindqvist, Claudia B. Maier, Vera J.C. Mc Carthy, Ingeborg Strømseng Sjetne, Lars E. Eriksson, Lisa Smeds Aleniu

International Journal of Nursing Studies.2024; 154: 104754. CrossRef - Transformational nurse leadership attributes in German hospitals pursuing organization-wide change via Magnet® or Pathway® principles: results from a qualitative study

Joan Kleine, Julia Köppen, Carolin Gurisch, Claudia B. Maier

BMC Health Services Research.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - The effect of work-family conflict on employee well-being among physicians: the mediating role of job satisfaction and work engagement

Xin Yang, Xiangou Kong, Meixi Qian, Xiaolin Zhang, Lingxi Li, Shang Gao, Liangwen Ning, Xihe Yu

BMC Psychology.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Mental Health of Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Bashar I. Alzghoul

The Open Public Health Journal.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Evaluation of the mental health status of intensive care unit healthcare workers at the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic

Ceren Meriç Özgündüz, Murat Bıçakçıoğlu, Ayse Sahin Tutak, Arman Özgündüz

Frontiers in Public Health.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Supporting employees with mental illness and reducing mental illness-related stigma in the workplace: an expert survey

Bridget Hogg, Ana Moreno-Alcázar, Mónika Ditta Tóth, Ilinca Serbanescu, Birgit Aust, Caleb Leduc, Charlotte Paterson, Fotini Tsantilla, Kahar Abdulla, Arlinda Cerga-Pashoja, Johanna Cresswell-Smith, Naim Fanaj, Andia Meksi, Doireann Ni Dhalaigh, Hanna Rei

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience.2023; 273(3): 739. CrossRef - Depression and quality of life among Afghan healthcare workers: A cross-sectional survey study

Abdul Qadim Mohammadi, Ahmad Neyazi, Vanya Rangelova, Bijaya Kumar Padhi, Goodness Ogeyi Odey, Molly Unoh Ogbodum, Mark D. Griffiths

BMC Psychology.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Mental health of health professionals and their perspectives on mental health services in a conflict-affected setting: a qualitative study in health centres in the Gaza Strip during the COVID-19 pandemic

Teisi Tamming, Yuko Otake, Safa'a Aburahma, Mengxin Tan, Anas Shishtawi, Yahya El-Daour, Khalil Hamad, Akihiro Seita

BMJ Open.2023; 13(8): e066552. CrossRef - Psychedelic Use Among Psychiatric Medication Prescribers: Effects on Well-Being, Depression, Anxiety, and Associations with Patterns of Use, Reported Harms, and Transformative Mental States

Zachary Herrmann, Adam W. Levin, Steven P. Cole, Sarah Slabaugh, Brian Barnett, Andrew Penn, Rakesh Jain, Charles Raison, Bhavya Rajanna, Saundra Jain

Psychedelic Medicine.2023; 1(3): 139. CrossRef - COVID-19 and Women’s Mental Health during a Pandemic – A Scoping Review

Nileswar Das, Preethy Kathiresan, Pooja Shakya, Siddharth Sarkar

Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry.2023; 39(1): 4. CrossRef - Urgensi Kepesertaan BPJS Kesehatan Sebagai Syarat Peralihan Hak Atas Tanah Berdasarkan Instruksi Presiden Nomor 1 Tahun 2022 Tentang Optimalisasi Pelaksanaan Program Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional

Nur Dwi Safitri, Fauziyah Fauziyah

Indonesian Journal of Law and Justice.2023; 1(2): 10. CrossRef - Job burnout on subjective wellbeing among clinicians in China: the mediating role of mental health

Yingjie Fu, Derong Huang, Shuo Zhang, Jian Wang

Frontiers in Psychology.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Evaluation of Mental Health Status of the Pregnant Women Working in

Hospitals During Covid-19 Era: A Cross-Sectional Study

Mahboubeh Eslamzadeh, Bita Najjari, Maryam Emadzadeh, Zhaleh Feyzi, Farzaneh Modaresi, Sara Mirzaeian, Fatemeh Behdani, Aazam Sadat Heydari Yazdi

Current Women s Health Reviews.2023;[Epub] CrossRef - Factors Affecting the Psychological Health of Dental Care Professionals During Pandemic: A Systematic Review

Muhammad Faiz Mohd Hanim, Nursharhani Shariff, Intan Elliayana Mohammed, Mohd Yusmiaidil Putera Mohd Yusof, Budi Aslinie Md Sabri, Norashikin Yusof

Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences.2023; 19(s18): 83. CrossRef - A Model of Depression in University Faculty, Staff, and Health Care Workers Using an Automated Mental Health Screening Tool

Sharon Tucker, Bern Melnyk, Lanie Corona, Carlos Corona, Haley Roberts

Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine.2022; 64(7): 607. CrossRef - Emotional distress symptoms and their determinants: screening of non-clinical hospital staff in an Egyptian University hospital

Noha M. Ibrahim, Dina A. Gamal-Elden, Mohsen A. Gadallah, Sahar K. Kandil

BMC Psychiatry.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Influencing Factors of High PTSD Among Medical Staff During COVID-19: Evidences From Both Meta-analysis and Subgroup Analysis

Guojia Qi, Ping Yuan, Miao Qi, Xiuli Hu, Shangpeng Shi, Xiuquan Shi

Safety and Health at Work.2022; 13(3): 269. CrossRef - Sleep Quality among Healthcare Professionals in a Tertiary Care Hospital

Abinaya Ravi, Sivapriya KRS, Neethu George, Rock Britto, Anirudh Parthiban, Nagarajan Anukruthi

National Journal of Community Medicine.2022; 13(4): 213. CrossRef - Study of Complexity Systems in Public Health for Evaluating the Correlation between Mental Health and Age-Related Demographic Characteristics: A General Health Study

Fereshte Haghi, Shadi Goli, Rana Rezaei, Fatemeh Akhormi, Fatemeh Eskandari, Zeinab Nasr Isfahani, Mohsen Ahmadi

Journal of Healthcare Engineering.2022; 2022: 1. CrossRef - High Levels of Self-Reported Depressive Symptoms Among Physical Therapists and Physical Therapist Students Are Associated With Musculoskeletal Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study

Tomer Yona, Asaf Weisman, Uri Gottlieb, Youssef Masharawi

Physical Therapy.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - A workplace organisational intervention to improve hospital nurses’ and physicians’ mental health: study protocol for the Magnet4Europe wait list cluster randomised controlled trial

Walter Sermeus, Linda H Aiken, Jane Ball, Jackie Bridges, Luk Bruyneel, Reinhard Busse, Hans De Witte, Simon Dello, Jonathan Drennan, Lars E Eriksson, Peter Griffiths, Dorothea Kohnen, Julia Köppen, Rikard Lindqvist, Claudia Bettina Maier, Matthew D McHug

BMJ Open.2022; 12(7): e059159. CrossRef - Insomnia and Related Factors During the Delta Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Kingdom of Bahrain: A Cross-Sectional Study

Fatema Habbash, Afif Ben Salah, Amer Almarabheh, Haitham Jahrami

Nature and Science of Sleep.2022; Volume 14: 1963. CrossRef - Impact of Personality Traits and Socio-Demographic Factors on Depression among Doctors and Nurses

Thapasya Maya

ABC Journal of Advanced Research.2022; 11(1): 1. CrossRef - Sleep of Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Role of Atypical Work Schedules: A Scoping Review

Niamh Power, Michel Perreault, Manuela Ferrari, Philippe Boudreau, Diane B. Boivin

Journal of Biological Rhythms.2022; 37(4): 358. CrossRef - The “Healthcare Workers’ Wellbeing [Benessere Operatori]” Project: A Longitudinal Evaluation of Psychological Responses of Italian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Gaia Perego, Federica Cugnata, Chiara Brombin, Francesca Milano, Emanuele Preti, Rossella Di Pierro, Chiara De Panfilis, Fabio Madeddu, Valentina Elisabetta Di Mattei

Journal of Clinical Medicine.2022; 11(9): 2317. CrossRef - Anxiety, Depression and Burnout Levels of Turkish Healthcare Workers at the End of the First Period of COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey

Burak Uz, Esra Savaşan, Dila Soğancı

Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience.2022; 20(1): 97. CrossRef - Working Conditions and Long-Term Sickness Absence Due to Mental Disorders

Noora Heinonen, Tea Lallukka, Jouni Lahti, Olli Pietiläinen, Hilla Nordquist, Minna Mänty, Anu Katainen, Anne Kouvonen

Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine.2022; 64(2): 105. CrossRef - Mental Health Outcomes and Mental Hygiene in the COVID-19 Era: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Healthcare Workers from a Regional Hospital in Ghana

Reginald Arthur-Mensah, Genevieve Paintsiwaa Paintsil, Agnes Agudu Delali, Abigail Agartha Kyei

Psychology Research and Behavior Management.2022; Volume 15: 21. CrossRef - Delusional Infestation in Healthcare Professionals: Outcomes from a Multi-Centre Case Series

John Frewen, Peter Lepping, Jonathan M. R. Goulding, Stephen Walker, Anthony Bewley

Skin Health and Disease.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Challenges facing essential workers: a cross-sectional survey of the subjective mental health and well-being of New Zealand healthcare and ‘other’ essential workers during the COVID-19 lockdown

Caroline Bell, Jonathan Williman, Ben Beaglehole, James Stanley, Matthew Jenkins, Philip Gendall, Charlene Rapsey, Susanna Every-Palmer

BMJ Open.2021; 11(7): e048107. CrossRef - Gender differences in mental health problems of healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak

Shuai Liu, Lulu Yang, Chenxi Zhang, Yan Xu, Lidan Cai, Simeng Ma, Ying Wang, Zhongxiang Cai, Hui Du, Ruiting Li, Lijun Kang, Huirong Zheng, Zhongchun Liu, Bin Zhang

Journal of Psychiatric Research.2021; 137: 393. CrossRef - A closer look at the high burden of psychiatric disorders among healthcare workers in Egypt during the COVID-19 pandemic

Amr Ehab El-Qushayri, Abdullah Dahy, Abdullah Reda, Mariam Abdelmageed Mahmoud, Sarah Abdel Mageed, Ahmed Mostafa Ahmed Kamel, Sherief Ghozy

Epidemiology and Health.2021; 43: e2021045. CrossRef - Mental Health Outcomes Amongst Health Care Workers During COVID 19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia

Maha Al Ammari, Khizra Sultana, Abin Thomas, Lolowa Al Swaidan, Nouf Al Harthi

Frontiers in Psychiatry.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Burnout and Presenteeism among Healthcare Workers in Nigeria: Implications for Patient Care, Occupational Health and Workforce Productivity

Arinze D.G. Nwosu, Edmund Ossai, Okechukwu Onwuasoigwe, Maureen Ezeigweneme, Jude Okpamen

Journal of Public Health Research.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - An Open Trial of the Effectiveness, Program Usage, and User Experience of Internet-based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Mixed Anxiety and Depression for Healthcare Workers on Disability Leave

Andrew Miki, Mark A. Lau, Hoora Moradian

Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine.2021; 63(10): 865. CrossRef - Anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Maxime Marvaldi, Jasmina Mallet, Caroline Dubertret, Marie Rose Moro, Sélim Benjamin Guessoum

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews.2021; 126: 252. CrossRef - Moral Injury and Light Triad Traits: Anxiety and Depression in Health-Care Personnel During the Coronavirus-2019 Pandemic in Honduras

Elizabeth A. Rodríguez, Maitée Agüero-Flores, Miguel Landa-Blanco, David Agurcia, Cindy Santos-Midence

Hispanic Health Care International.2021; 19(4): 230. CrossRef - Mental Disorders Among Health Care Workers at the Early Phase of COVID-19 Pandemic in Kenya; Findings of an Online Descriptive Survey

Edith Kamaru Kwobah, Ann Mwangi, Kirtika Patel, Thomas Mwogi, Robert Kiptoo, Lukoye Atwoli

Frontiers in Psychiatry.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - Association of Sickness Absence With Severe Psychiatric Outcomes in a Brazilian Health Workforce

Claudia Szlejf, Aline Kumow, Rafael Dadão, Etienne Duim, Vanessa Moraes Assalim

Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine.2020; 62(10): e543. CrossRef Obstetrics Healthcare Providers’ Mental Health and Quality of Life During COVID-19 Pandemic: Multicenter Study from Eight Cities in Iran

Homeira Vafaei, Shohreh Roozmeh, Kamran Hessami, Maryam Kasraeian, Nasrin Asadi, Azam Faraji, Khadije Bazrafshan, Najmieh Saadati, Soudabeh Kazemi Aski, Elahe Zarean, Mahboobeh Golshahi, Mansoureh Haghiri, Nazanin Abdi, Reza Tabrizi, Bahram Heshmati, Elha

Psychology Research and Behavior Management.2020; Volume 13: 563. CrossRef- Ethical dilemmas faced by health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic: Issues, implications and suggestions

Vikas Menon, Susanta Kumar Padhy

Asian Journal of Psychiatry.2020; 51: 102116. CrossRef - Surgical Locker room Environment: Understanding the Hazards (SLEUTH) study

Rowan David, Bridget Heijkoop, Arman A. Kahokehr

ANZ Journal of Surgery.2020; 90(10): 1943. CrossRef - Anxiety and hopelessness levels in COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative study of healthcare professionals and other community sample in Turkey

Yunus Hacimusalar, Aybeniz Civan Kahve, Alisan Burak Yasar, Mehmet Sinan Aydin

Journal of Psychiatric Research.2020; 129: 181. CrossRef - The relationship between occupational stress, psychological distress symptoms, and social support among Jordanian healthcare professionals

Wafa'a F. Ta'an, Tariq N. Al‐Dwaikat, Khulod Dardas, Ahmad H. Rayan

Nursing Forum.2020; 55(4): 763. CrossRef - Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals

Angela M Kunzler, Isabella Helmreich, Andrea Chmitorz, Jochem König, Harald Binder, Michèle Wessa, Klaus Lieb

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - DANGER! Crisis Health Workers at Risk

Mason Harrell, Saranya A. Selvaraj, Mia Edgar

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.2020; 17(15): 5270. CrossRef - Burnout, Mental Health, and Quality of Life Among Employees of a Malaysian Hospital: A Cross-sectional Study

Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, Chea Ping Tiong

Annals of Work Exposures and Health.2020; 64(9): 1007. CrossRef - Job Satisfaction and Psychiatric Morbidity among Resident Doctors in Selected Teaching Hospitals in Southern Nigeria: A web-based Survey

Segun Bello, Rotimi Felix Afolabi, David Ayobami Adewole

Journal of Occupational Health and Epidemiology.2019; 8(4): 199. CrossRef - Health anxiety in medical employees: A multicentre study

Qingsong Chen, Yuqun Zhang, Dongyun Zhuang, Xueqin Mao, Guolin Mi, Dijuan Wang, Xiangdong Du, Zhenghui Yi, Xinhua Shen, Yuxiu Sui, Huajie Li, Yin Cao, Zufu Zhu, Zhenghua Hou, Qibin Li, Yonggui Yuan

Journal of International Medical Research.2019; 47(10): 4854. CrossRef - Sleep problems of healthcare workers in tertiary hospital and influencing factors identified through a multilevel analysis: a cross-sectional study in China

Huan Liu, Jingjing Liu, Mingxi Chen, Xiao Tan, Tong Zheng, Zheng Kang, Lijun Gao, Mingli Jiao, Ning Ning, Libo Liang, Qunhong Wu, Yanhua Hao

BMJ Open.2019; 9(12): e032239. CrossRef - Exploring the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavioural Responses of Healthcare Students towards Mental Illnesses—A Qualitative Study

Taylor Riffel, Shu-Ping Chen

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.2019; 17(1): 25. CrossRef

Fig. 1

| Prevalence cases | All insured employees | Workers in healthcare industry | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both (n = 13,869,767) | % | Male (n = 8,535,138) | % | Female (n = 5,334,629) | % | Both (n = 752,181) | % | Male (n = 196,957) | % | Female (n = 555,224) | % | |

| Mood disordersa | 217,752 | 1.57 | 111,269 | 1.30 | 106,483 | 2.00 | 13,709 | 1.82 | 3089 | 1.57 | 10,620 | 1.91 |

| Anxiety disordersb | 250,895 | 1.81 | 130,570 | 1.50 | 120,325 | 2.26 | 15,570 | 2.07 | 3528 | 1.79 | 12,042 | 2.17 |

| Sleep disordersc | 228,119 | 1.64 | 116,208 | 1.36 | 111,911 | 2.10 | 24,965 | 3.32 | 6861 | 3.48 | 18,104 | 3.26 |

| Any psychiatric disordersd | 728,767 | 5.25 | 380,223 | 4.45 | 348,544 | 6.53 | 55,139 | 7.33 | 13,512 | 6.86 | 41,627 | 7.50 |

| Age-standardized prevalence estimate (%) | All insured employees | Workers in healthcare industry | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both | 95% CI | Male | 95% CI | Female | 95% CI | Both | 95% CI | Male | 95% CI | Female | 95% CI | |

| Mood disordersa | 1.69 | 1.68–1.70 | 1.30 | 1.29–1.31 | 2.08 | 2.07–2.10 | 1.93 | 1.83–2.03 | 1.63 | 1.45–1.81 | 2.24 | 2.17–2.31 |

| Anxiety disordersb | 1.93 | 1.92–1.93 | 1.49 | 1.48–1.50 | 2.37 | 2.36–2.39 | 2.18 | 3.39–3.54 | 1.83 | 1.66–1.99 | 2.53 | 2.46–2.60 |

| Sleep disordersc | 1.76 | 1.75–1.77 | 1.33 | 1.32–1.34 | 2.20 | 2.18–2.21 | 3.47 | 2.08–2.27 | 3.33 | 3.21–3.45 | 3.62 | 3.53–3.71 |

| Any psychiatric disordersd | 5.59 | 5.57–5.60 | 4.38 | 4.36–4.40 | 6.83 | 6.80–6.85 | 7.58 | 7.43–7.74 | 6.77 | 6.50–7.04 | 8.43 | 8.30–8.56 |

| Variables | All insured employees | Workers in healthcare industry | Reference group | Standardized differencea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 13,869,767) | % | (n = 752,181) | % | (n = 3,008,724) | % | pre-match | post-match | |

| Age | − 0.328 | 0.000 | ||||||

| < 20 | 100,403 | 0.72 | 2578 | 0.34 | 10,312 | 0.34 | ||

| 20–29 | 2,424,686 | 17.48 | 218,899 | 29.10 | 875,596 | 29.10 | ||

| 30–39 | 4,151,253 | 29.93 | 239,610 | 31.86 | 958,440 | 31.86 | ||

| 40–49 | 3,942,566 | 28.43 | 180,096 | 23.94 | 720,384 | 23.94 | ||

| 50–59 | 2,721,879 | 19.62 | 93,849 | 12.48 | 375,396 | 12.48 | ||

| ≥60 | 528,980 | 3.81 | 17,149 | 2.28 | 68,596 | 2.28 | ||

| Mean | 40.4 ± 10.8 | 37.0 ± 10.5 | 37.1 ± 10.5 | |||||

| Income level | −0.056 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Q1 | 3,471,369 | 25.03 | 163,190 | 21.70 | 652,760 | 21.70 | ||

| Q2 | 3,440,340 | 24.80 | 247,161 | 32.86 | 988,644 | 32.86 | ||

| Q3 | 3,483,627 | 25.12 | 186,525 | 24.80 | 746,100 | 24.80 | ||

| Q4 | 3,474,431 | 25.05 | 155,305 | 20.65 | 621,220 | 20.65 | ||

| Sex | −0.056 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Male | 8,535,138 | 61.54 | 196,957 | 26.18 | 787,828 | 26.18 | ||

| Female | 5,334,629 | 38.46 | 555,224 | 73.82 | 2,220,896 | 73.82 | ||

| Mood disordersa | Anxiety disordersb | Sleep disordersc | Any psychiatric disordersd | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases (%) | ORe | 95%CI | Number of cases (%) | ORe | 95%CI | Number of cases (%) | ORe | 95%CI | Number of cases (%) | ORe | 95%CI | |

| Both | ||||||||||||

| Workers in healthcare industry | 13,709 (1.82) | 1.13 | 1.11 - 1.15 | 15,570 (2.07) | 1.15 | 1.13 - 1.17 | 24,965 (3.32) | 2.21 | 2.18 - 2.24 | 55,139 (7.33) | 1.44 | 1.43 - 1.46 |

| Reference group | 48,769 (1.62) | 1 | 54,266 (1.80) | 1 | 46,197 (1.54) | 1 | 156,902 (5.21) | 1 | ||||

| Male | ||||||||||||

| Workers in healthcare industry | 3,089 (1.57) | 1.24 | 1.19 - 1.29 | 3,528 (1.79) | 1.19 | 1.14 - 1.23 | 6,861 (3.48) | 2.78 | 2.69 - 2.86 | 13,512 (6.86) | 1.62 | 1.59 - 1.66 |

| Reference group | 10,037 (1.27) | 1 | 11,952 (1.52) | 1 | 10,172 (1.29) | 1 | 34,362 (4.36) | 1 | ||||

| Female | ||||||||||||

| Workers in healthcare industry | 10,620 (1.91) | 1.10 | 1.08 - 1.12 | 12,042 (2.17) | 1.14 | 1.12 - 1.17 | 18,104 (3.26) | 2.05 | 2.01 - 2.09 | 41,627 (7.50) | 1.39 | 1.38 - 1.41 |

| Reference group | 38,732 (1.74) | 1 | 42,314 (1.91) | 1 | 36,025 (1.62) | 1 | 122,540 (5.52) | 1 | ||||

aMood disorders include diagnosis code of F30~F39 by Korean Standard Classification of Diseases

bAnxiety disorders include diagnosis code of F41 and F41.0~F41.9

cSleep disorders include diagnosis code of F51, F51.0~F51.2, F51.8, F51.9, G47, G47.0, G47.1, G47.2, G47.8, and G47.9

dAny psychiatric disorders include diagnosis code of any of F00~F99 and sleep disorders

aMood disorders include diagnosis code of F30~F39 by Korean Standard Classification of Diseases

bAnxiety disorders include diagnosis code of F41 and F41.0~F41.9

cSleep disorders include diagnosis code of F51, F51.0~F51.2, F51.8, F51.9, G47, G47.0, G47.1, G47.2, G47.8, and G47.9

dAny psychiatric disorders include diagnosis code of any of F00~F99 and sleep disorders

aStandardized differences in age was calculated by categorical variables of age group

aMood disorders includes diagnosis code of F30~F39 by Korean Standard Classification of Diseases

bAnxiety disorders includes diagnosis code of F41 and F41.0~F41.9

cSleep disorders includes diagnosis code of F51, F51.0~F51.2, F51.8, F51.9, G47, G47.0, G47.1, G47.2, G47.8, and G47.9

dAny psychiatric disorders includes diagnosis code of any of F00~F99 and sleep disorders

eNo other covariates included in conditional logistic model

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite