Abstract

This study explores the theoretical foundations and practical applications of medical certification within the sickness benefit systems, particularly in the context of Korea’s pilot program and its planned national rollout. While sickness benefit systems have long existed in many Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, Korea has only recently initiated pilot projects, largely prompted by the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. These systems aim to compensate for income loss due to illness or injury, and medical certification plays a central role in determining eligibility and work ability. This study defines medical certification as a two-stage process: clinical diagnosis and formal assessment of a worker’s ability to return-to-work. The dual nature highlights the distinct objectives of the medical treatment and social security policies. Drawing on international practices, this study reviews the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) as a key global framework for assessing disability and work ability, although it acknowledges the limitations of its application to sickness benefits. The research emphasizes a shift in global trends toward return-to-work–oriented certification models, such as the UK’s “fit note” system, which focuses on evaluating fitness-for-work rather than merely documenting illness. Sweden and Japan also offer models that integrate rehabilitation with flexible work accommodations. Three key issues were identified in Korea’s system: the role of medical certification and concerns about moral hazard, the burden of proof and workload on physicians, and public perceptions of the program’s purpose. We believe that medical certification should not only verify illness but also support early intervention and a healthy workforce. Ultimately, this study advocates for a balanced and efficient medical certification system tailored to Korea’s healthcare context closely aligning with labor market policies to ensure long-term sustenance and integration of the sickness benefit program.

-

Keywords: Sick leave; Sickness benefit; Return to work; Disability evaluation; Insurance, health

BACKGROUND

The sickness benefit system is one of the oldest forms of social insurance in the world. It originated in 1883 in the Weimar Republic of Germany as part of the National Health Insurance.

1 Subsequently, it penetrated the European and Western societies. As of 2025, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries, except South Korea, Switzerland, and approximately 20 states in the United States, have introduced sickness benefit systems.

2 Also, Switzerland does not have a nationwide sickness benefit program; paid sick leave is mandated by law and private insurance managed by quasi-public institutions effectively functions as a public sickness benefit scheme.

3 Japan’s sickness benefit system began alongside its health insurance program and has been in place for more than 90 years.

4

Meanwhile, discussions on introducing a sickness benefit system in South Korea began in the 2000s, mainly among academics. However, with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, demands for the right to take time off when sick increased, and the issue became a major policy discussion point for the government. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Health and Welfare in Korea launched pilot projects for a sickness benefit system in 2022 and continued through 2025 with plans to fully implement the program.

5

Sickness benefit systems in countries other than Korea have evolved in response to socioeconomic conditions and public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Sweden reduced the waiting period to zero during the COVID-19 pandemic and reinstated it after the emergency ended, whereas Korea introduced its first pilot program for a sickness benefit scheme during the same period.

2 Korea, which is currently extending its pilot initiatives and preparing a full program, must thoroughly examine these transformations in its global sickness benefit schemes. This study focuses on the medical certification system, one of the core elements of the sickness benefit program, which is closely related to medicine.

In this study, the term “medical certification system” denotes the full sequence of medical interventions triggered when an employee applies for sickness benefits. Within this framework, “medical certification” refers specifically to the physician’s verification of the employee’s medical condition and fitness-for-work duties. This study explores the role of the medical certification framework within the sickness benefit system and examines both the theoretical and practical aspects of returning to work as the central objective. This study aims to establish a literature-based rationale and practical implications for the forthcoming nationwide implementation of Korea’s sickness benefit program and for future research.

METHODS

We combined a narrative literature review with an examination of the pilot scheme. First, drawing on the medical literature that has extensively addressed sickness benefits

6-8 and foreign sources, we provide a theoretical overview of medical certification or sickness benefit systems. From an occupational medicine perspective, we consider the definition of sickness, concept of medical certification, international framework for disability assessment, changing role of medical certification, and medical certification system aimed at returning to work.

Second, with the cooperation of the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the National Health Insurance Service, we collected expert opinions and administrative data on the pilot program and reviewed international studies on medical certification in sickness benefit systems. Based on this evidence, the research team identified three issues likely to be pivotal for the Korean system—namely, the role of medical certification, the allocation of the burden of proof vis-à-vis physicians’ responsibilities, and societal perceptions of the scheme—and organized the discussion around these themes.

REVIEWS

Medicine and the sickness benefit schemes

When a worker develops an illness or injury, part or all of their work ability may be reduced, potentially leading to a loss of income. The sickness benefit system is a form of social insurance designed to compensate for the lost income. Medical certification is indispensable for the proper functioning of these systems, and consists of the following two steps: First, the primary step is required for the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of a worker’s condition. Subsequently, a secondary step is required to evaluate the reduction and restoration of the workers’ capacities to perform their work. Although the manner, extent, and rigor of medical assessments differ by country, all sickness benefit schemes are inevitably closely linked to medical service delivery systems.

However, the perspective of a physician who diagnoses a patient’s illness may differ from that of the national government, which seeks to administer sickness benefits to employees. The primary goal of a physician in diagnosing a disease is to treat the patient,

9 whereas the objective of a sickness benefit system is to compensate those who are temporarily unable to work. To understand this distinction more clearly, it is helpful to consider conceptual classifications of maladies.

10

In

Table 1, the term “malady” refers to the shift from a healthy state to an unhealthy one, as well as the unhealthy state itself, in a broad sense. Treatment refers to the interventions that move an individual from an unhealthy to a healthy state. The concept of malady can be divided further. “Illness” refers to a subjective experience of discomfort or pain, such as that associated with mental illness. “Disease” centers on the pathological process deviating from normal physiology and is the most commonly used term in medicine. “Disorder” denotes a partial loss of the bodily function. In contrast, “sickness” indicates an unhealthy state that is publicly recognized or displayed—this term corresponds to “sickness” in the context of sickness benefits. “Disability” refers to a permanent and irreversible loss of function.

9,10

The reason for using the term sickness is used rather than disease or disability in the sickness benefit system is that it assumes workers are temporarily unable to work because of illness. According to this definition, ‘sickness’ in the context of sickness benefits refers to an unhealthy condition that renders the worker or patient partially or wholly incapable of working and requires external or public confirmation of the condition. When the sickness leave period is short or symptoms are mild, no documentation may be required to receive sickness benefits, or the worker may use other avenues such as legally mandated paid sick leave. However, most sickness benefit systems require varying degrees of medical evidence through formal certifications. This requirement forms the basis of the system’s medical certification framework, the most prominent of which is the sickness benefit medical certificate issued by physicians.

In other words, medical certification in the sickness benefit system is a combination of a medical judgement that a worker has a health problem and a social judgement that the worker is unable to work because of the health condition or that working would adversely affect the course of the condition. Based on this judgement, the process of issuing an official document states that income compensation is necessary. This is slightly different from issuing a medical certificate that identifies a patient’s current medical condition.

Work disability evaluation and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

The most important international guide for assessing work ability, which is at the heart of the medical certification process for the sickness benefit scheme, is the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), published by the World Health Organization in 2001.

11 The ICF is the most widely used medical tool for objectively measuring and assessing a patient's physical or mental capabilities. It is widely applied internationally in various social security systems, including sickness benefits, and is the basis for many medical certification schemes.

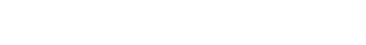

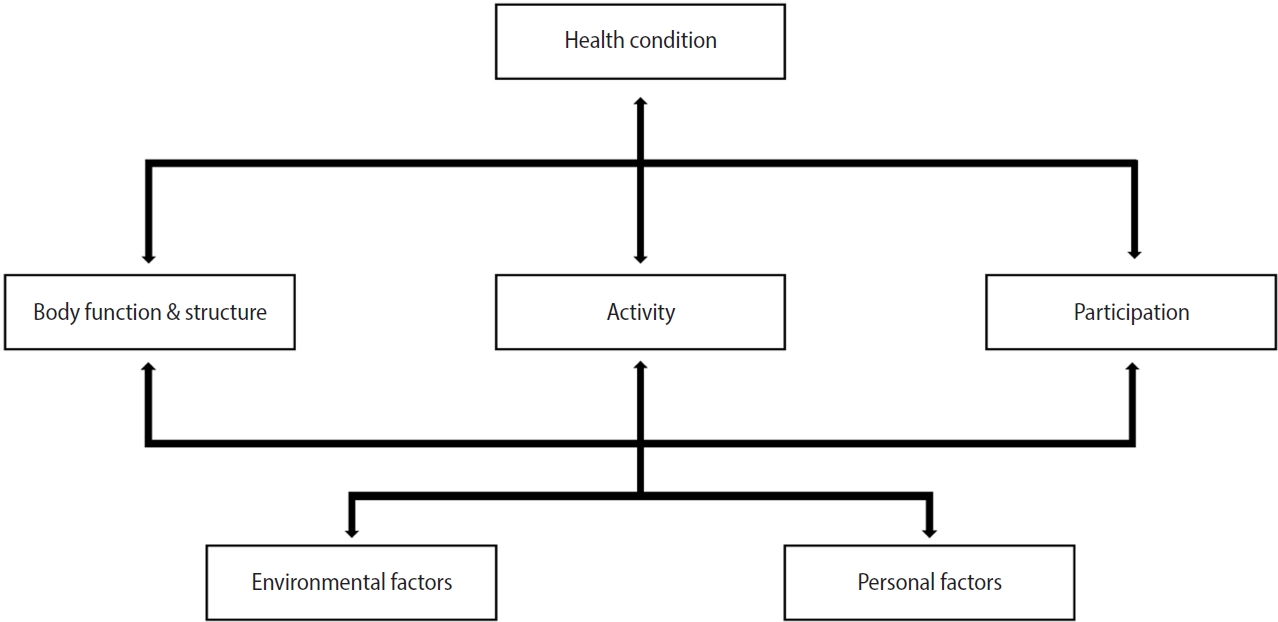

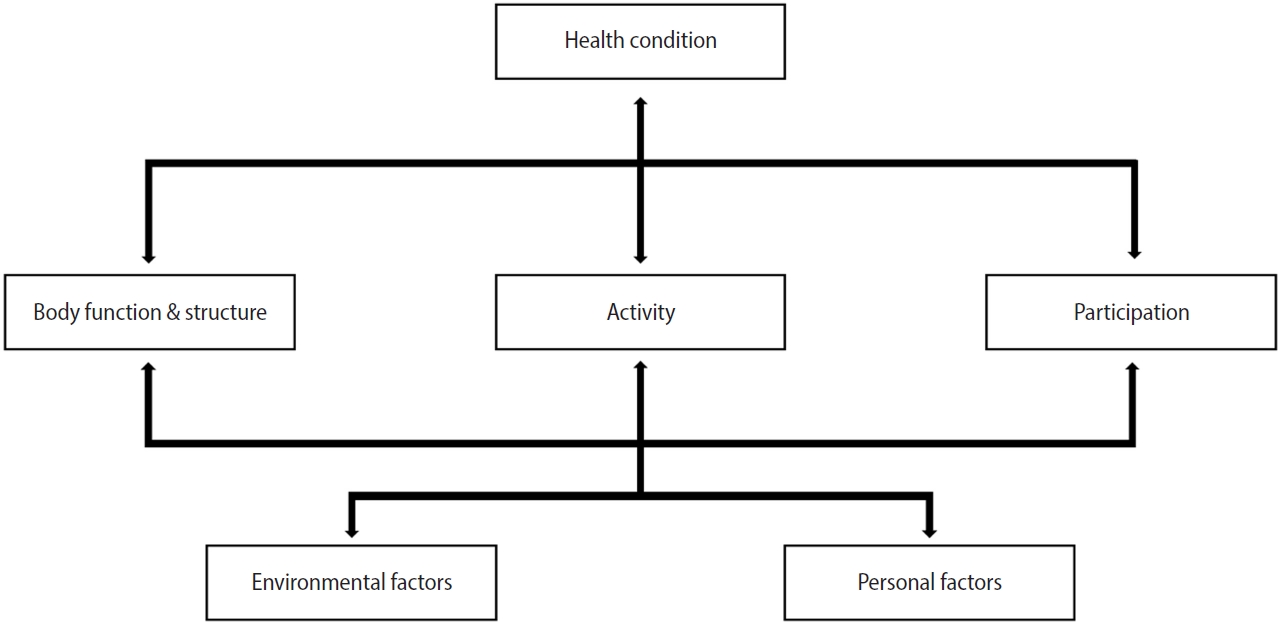

The ICF employs a bio-psycho-social approach to health and disease, positing that body functions, structures, activities, and participation interact with environmental and personal factors to define the overall health status (

Fig. 1). Specifically, the classification included 485 categories for body functions, 302 for body structures, 384 for activities and participation, and 253 for environmental factors, organized into four levels for a total of 1,424 categories. Additionally, 1,122 disabilities were defined within this framework. The “activities and participation” and “environmental factors” domains are well-suited for use in social security systems.

In particular, the ICF is widely applied for work disability evaluations, estimating the period during which a person cannot work, and for disability assessments associated with disability benefits or pensions. Conceptually, it is difficult to draw a clear distinction between work ability evaluations in sickness benefit systems and disability assessments in disability-related social security systems. In many cases, once a worker is deemed unable to work for a year or more, they often transition out of sickness benefit coverage.

12 In Sweden, where sickness and disability benefits are seamlessly linked, work disability evaluations determine eligibility.

13

Nevertheless, the ICF does not address every component of work ability evaluation required by sickness benefit systems. It does not offer detailed guidelines on prognosis or evaluation methods, nor does it include social and medical histories in the disability assessment. Moreover, there are no established criteria or definitions specific to “work ability.”

6 Thus, while the ICF is the most universally accepted international framework in medicine and meets the need for the public evaluation of sickness benefits, creating a customized medical certification system aligned with society’s specific needs and continually refining it in response to social change remains imperative. Therefore, many countries have established various forms of medical certification systems that reflect the elements of the ICF but vary depending on the level of coverage and policy objectives of the country’s sickness benefit system.

Many countries offering sickness benefits and other social security programs face significant challenges and are under constant pressure to undertake reforms.

8 For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous countries have turned to sickness benefits to compensate workers ‘unable to work’ because of infection or quarantine. Many have introduced remote medical consultations to ease the burden of administrative procedures and documentation.

7 Following the end of the pandemic, Europe saw a substantial increase in expenditures related to sickness benefits, leading to wide-ranging calls for reforms in health insurance systems, including Germany’s sickness benefit framework.

15 Moreover, broader demographic shifts such as an aging workforce suggest that these reform pressures will continue.

Reflecting these changes, the focus of medical certification in many sickness benefit systems has shifted over time from merely identifying an illness and verifying treatment or recovery periods to prioritizing return-to-work through vocational rehabilitation.

8,16 The OECD has strongly recommended this shift.

To capitalize on the ICF for social security programs, including sickness benefits, and to address its known limitations, an ICF Core Set for Vocational Rehabilitation was created at the 2010 ICF Consensus Conference.

14,17 The comprehensive ICF Core Set for Vocational Rehabilitation consists of 90 categories, whereas the brief version includes 13 second-level categories (

Table 2). In Europe, the European Union of Medicine in Assurance and Social Security, a consortium of 15 countries, has been developing ICF Core Sets for several purposes since 2004, and can be considered a forerunner to the ICF Consensus Conference.

This paradigm shift is inevitable. with repeated large-scale public health emergencies and the ongoing aging of the labor force; it is increasingly common for sickness-benefit recipients to have multiple physical or mental health conditions. Biomedical disability assessments cannot fully address the complexities of these workers’ situations, nor can they meet all administrative demands of the labor market. Consequently, disability evaluations now emphasize vocational rehabilitation rather than solely focusing on the disease.

18,19 Vocational rehabilitation-based work-disability evaluations are multidisciplinary and involve several stakeholders. Although disease-centered approaches focus on determining eligibility for benefits, vocational rehabilitation aims to facilitate return-to-work.

20

A well-noted example of a sickness benefit medical certification system pivoting toward vocational rehabilitation and return-to-work is the “fit note” system in the United Kingdom. It was implemented nationwide in 2010, the fit note system has also been adopted in Norway, Ireland, and other countries.

7,21-23 Before the introduction of the fit note, the UK used a “sick note” certification format that primarily documented workers’ illnesses and reduced work ability. In contrast, the fit note evaluates “fitness-for-work” based on the individual’s current health status. This is similar to the concept of fitness-for-work assessment in occupational medicine.

23-25

Sweden adopted a broader government approach. If a worker’s sickness benefit claim is expected to exceed a certain duration, the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (Försäkringskassan) intervenes at each stage. These measures include partial sickness benefits, identifying alternative tasks within the worker’s current workplace, and exploring job opportunities in different workplaces.

26-29

In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare trains coordinators to facilitate the coexistence of work and illness, offering explicit guidelines for managing conditions such as cancer. For instance, cancer survivors may continue to work during chemotherapy or other treatments with the aid of reduced working hours and antidiscrimination measures in the workplace.

4,5,30

In summary, the medical certification system in sickness benefit schemes must provide an objective, evidence-based evaluation of illness and prognosis, while publicly documenting reduced work ability through disability evaluations. Such evaluations should be part of an integrated medical certification system that ultimately targets return-to-work. This study proposes a conceptual model illustrating how a sickness-benefit medical certification system can enhance return-to-work outcomes and clarifies the impact of a functioning or failing certification process.

Return-to-work refers to a series of steps that help reintegrate employees into their occupational roles after their work ability has been compromised by illness or injury. In a narrower sense, this signifies the positive health outcomes of successfully resuming employment. Sickness benefits can influence health-seeking behavior by ensuring timely treatment and enabling adequate recovery period for those who might otherwise have to work through illness. This leads to an improved prognosis and more favorable return-to-work outcomes.

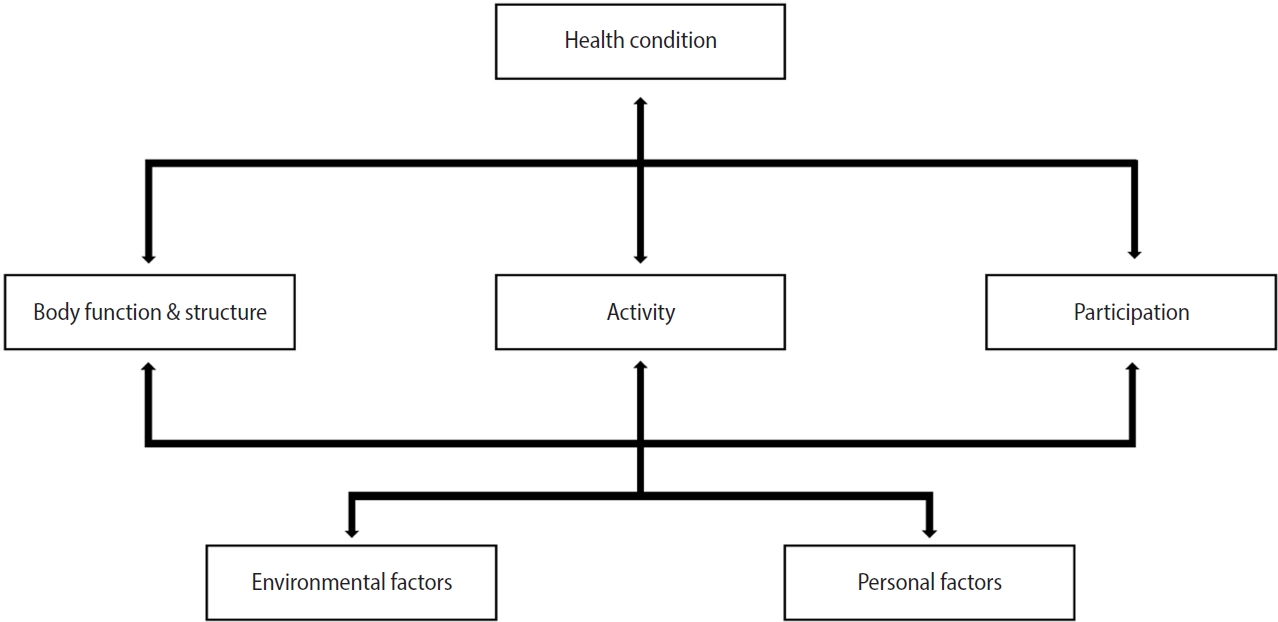

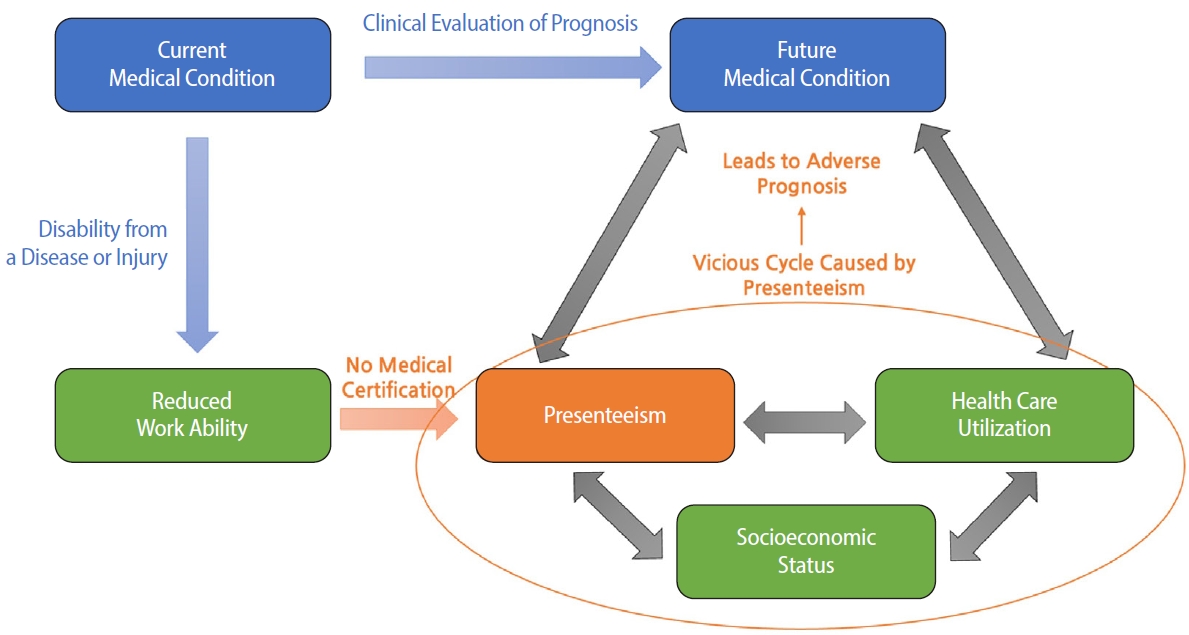

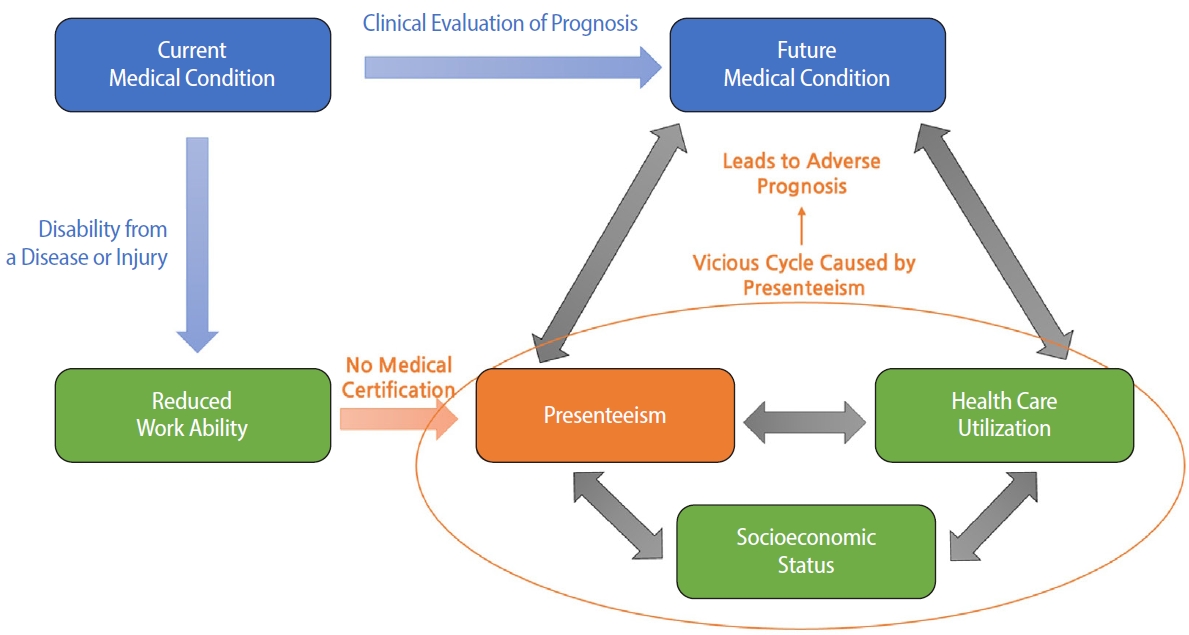

Fig. 2 shows the occupational health trajectory when a worker’s condition deteriorates to an illness, reducing their work ability in the absence of a functioning sickness benefit system. Without a sickness benefit system and medical certification, work disability assessment may present with inaccuracies, increasing the risk of presenteeism. This might create a negative cycle of deteriorating socioeconomic conditions and reduced healthcare utilization, ultimately affecting both prognosis and the broader socioeconomic environment.

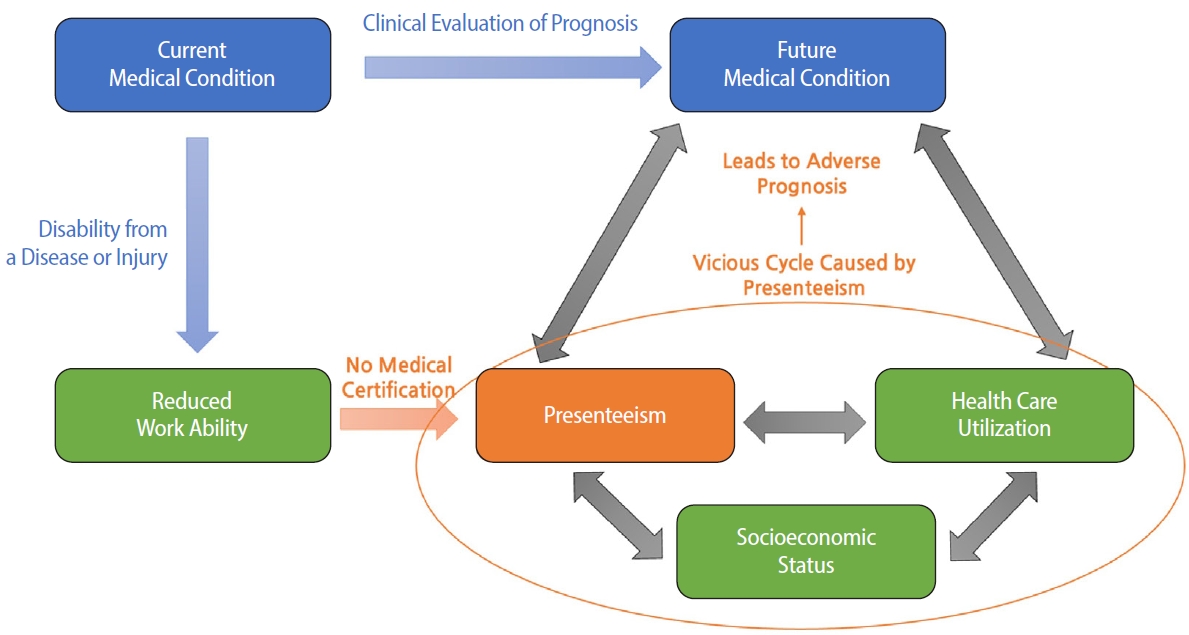

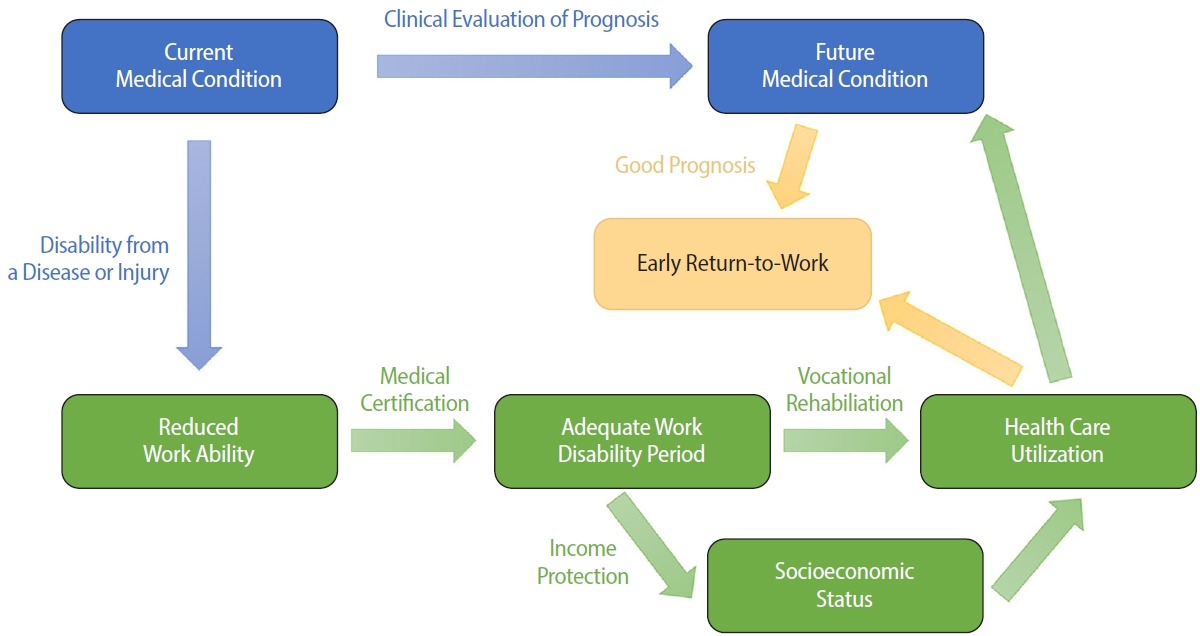

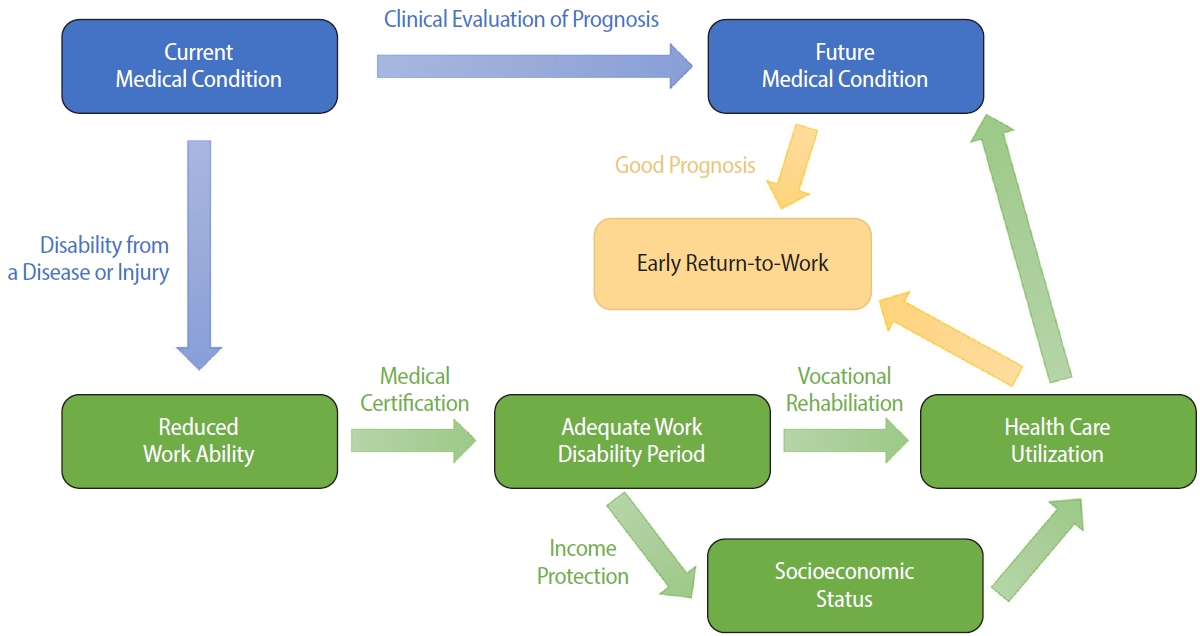

Conversely, when the sickness benefit system functions properly, presenteeism can be prevented by accurately assessing the required work disability period using a medical certification system (

Fig. 3). This mechanism helps to achieve a faster return-to-work, improving both healthcare utilization patterns and socioeconomic outcomes. It can also create a virtuous cycle of early diagnosis, treatment, and return-to-work to maintain a healthy workforce. A better clinical prognosis is often associated with such improvements, although other medical factors may also play a role.

Finally, a medical certification system that focuses on returning to work is an important policy instrument in the context of universal health coverage and active labor market policies.

DISCUSSION

Based on the theoretical considerations of medical certification within the sickness benefit system, the discussion addresses key issues in designing, establishing, and implementing in Korea through a pilot project. Relevant issues were selected based on policy research related to the pilot program for sickness benefits conducted by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, the role of medical certification, the burden of proof and workload of physicians, and public perception of the objectives of the sickness benefit system.

3,5,31

Since the medical certification system is responsible for diagnosing illnesses and determining the appropriate period of work disability, it serves as a gatekeeper against moral hazards. Physicians who issue sickness benefit certificates are expected to act as first-line gatekeepers.

31

In insurance theory, moral hazard, in a narrow sense, arises when insurance premiums are uniformly low or identical for high-risk individuals compared to low-risk individuals, undermining risk-spreading functions.

32 In social insurance, moral hazard generally refers to scenarios in which individuals with a disability are capable of working or in which system design discourages work by offering benefits that exceed potential earnings. Countries with extensive welfare programs, such as Sweden, have rigorously studied the prevention of moral hazards in sickness benefits.

33,34 Interpretations of moral laxity vary depending on the direction of a country’s social insurance system or social security policy. However, as a latecomer, the medical accreditation system is one of the most important elements of the system design in terms of sustainability and financial stability.

The current Korean pilot program’s benefit levels and certification rigor appear unlikely to cause severe moral hazards, as seen in other systems. However, there are ongoing concerns about the depletion of the National Health Insurance fund,

35 the supply of medical services being dominated by the private sector, the subscription rate for private insurance that provides immediate payments being quite high, and the number of medical visits being high compared with other countries. A social security system that did not previously exist in Korea was introduced. Therefore, it is necessary to design an efficient medical certification system to ensure its stable operation and establishment.

Recent research indicates that this gatekeeping role can be challenging and that overreliance on physicians may have unintended consequences. A 2022 qualitative study in Norway involving 22 general practitioners who frequently issued medical certificates found that refusing or reducing a patient’s requested sick leave required significantly more time. Consequently, physicians often do not address patient requests. Certification fees have little influence on the decision-making processes.

36 The limited time physicians had for each consultation was identified as the biggest obstacle to effective gatekeeping. Another Norwegian study analyzed the economic balance of falsely suspecting someone with hard-to-verify complaints of malingering versus issuing a sick certificate without suspicion.

37 Research in Sweden suggests that close communication and joint training between social insurance agencies and healthcare providers can offset time and knowledge constraints among clinicians.

38

Lessons from other countries and research on the gatekeeping role of medical certification in sickness benefit systems highlight the need for a system with rigor proportional to the level of benefit coverage. In addition, a suitable and efficient medical certification system should be established considering Korea’s medical usage behavior and service delivery methods.

Burden of proof and physician workload

Within the sickness benefit system, the medical certification framework ultimately serves to prove eligibility. The primary onus of proof is the worker or patient who applies for benefits. Regardless of how clearly a person’s reduced work ability is demonstrated, they cannot receive benefits without submitting a claim to the relevant authorities. If a worker’s burden of proof is too low, the risk of moral hazard increases; however, if it is too high, it may act as a barrier to accessing benefits. Both scenarios undermine the system’s goal of prompt medical intervention and a successful return-to-work. Developing viable solutions to this challenge is critical for implementing Korea’s sickness benefit scheme. It is essential to collect empirical data during the pilot program on how the burden of proof and physicians’ workload are balanced in practice and reflect these findings in the design of the permanent system.

Physicians must provide accurate medical evaluations and advise patients to optimize their health outcomes. Certifying an appropriate work disability period should be based on a sound medical assessment; however, it can add administrative or legal layers to the physician–patient relationship. If either the patient or physician believes that the physician’s role should be restricted to biomedical care, it becomes more difficult to integrate proof of work disability into routine clinical practice. Multiple studies from other countries have reported that shifting this administrative responsibility onto general practitioners increases workload and creates additional challenges.

23,36,39-42

If the burden of proof is disproportionately placed on physicians, it is likely to impose significant workload pressure and precipitate an overall decline in service quality. Some countries have relaxed these obligations during the COVID-19 pandemic by allowing remote consultations or, in the case of the UK, permitting nurses and vocational rehabilitation professionals to issue fit notes. However, some studies have found that if a certifier does not personally know the patient, the administrative burden on physicians can increase.

7 When the number of sickness benefit claims increased substantially, the UK reconsidered reverting its authority to issue fit notes solely to physicians. These findings illustrate that, while lightening physicians’ proof obligations can increase accessibility, it may also produce unintended side effects.

Government agencies oversee the financial and administrative management of sickness benefits to ensure that payments are made for legitimate claims. In Korea, this responsibility lies with the National Health Insurance Service. However, focusing excessively on administrative scrutiny of cash payouts may detract from enduring health promotion and return-to-work objectives. Therefore, a balanced approach to fostering system sustainability is essential.

Public perception of the objectives of sickness benefit scheme

One of the most pressing challenges in Korea’s healthcare delivery and social security environment is the pervasive role of private health insurance, commonly known as “indemnity health insurance.” By 2023, approximately 69% of Korean citizens will be enrolled in these plans.

43 When sickness or injury occurs, policyholders submit claims to their private insurance providers to receive reimbursements based on contractual terms. As Korea has never had a public program to replace wages lost due to illness or injury, the public may conflate sickness benefits with private insurance payouts triggered by medical diagnoses alone. The social security aim of sickness benefits, which extends beyond compensation for medical diagnoses to include facilitating early intervention, preventing prolonged loss of work ability, and ultimately promoting a timely return-to-work, may not be immediately apparent. A policy study for the pilot program emphasized the risk that beneficiaries may have misplaced perceptions of the system’s public purpose and may fail to distinguish it from private health insurance for illnesses.

44

In other words, whether the primary objective of the sickness benefit is income security as a welfare policy, the maintenance of a healthy workforce as part of a labor policy, or universal health coverage as a health policy can have a significant impact on the information the medical certification system requires from recipients and how that information is verified. When finalizing the system design, it should be clearly communicated that sickness benefits are not intended as simple compensation for diagnoses, but as a means to secure early medical intervention, shorten the work disability period, and ensure that workers can return-to-work sooner. This principle must be firmly embedded in medical certification frameworks.

45

CONCLUSIONS

Given the long global history of sickness benefit systems, numerous studies and debates have focused on medical certifications. Thoroughly integrating these insights is imperative for the successful adoption of sickness benefits in South Korea. Policymakers face a dual challenge: integrating the basic features of conventional work disability evaluations while simultaneously modernizing the system to address public health emergencies and demographic changes that unfold as rapidly in Korea as in many other Western countries.

Although a medical certification system should be established under clear and well-defined policy goals, the academic discourse has advanced, indicating that the role of sickness benefits should extend beyond income replacement and cash disbursements. Instead, it should focus on vocational rehabilitation and returning to work. This approach must be continuously nurtured to strengthen and refine the medical certification framework of Korea’s evolving sickness-benefit system.

Abbreviations

International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

NOTES

-

Competing interests

Inah Kim contributing editor of the Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. The remaining author has declared no conflicts of interest.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Kim Y, Kim I. Data curation: Kim Y. Formal analysis: Kim Y. Writing -original draft: Kim Y. Writing - review & editing: Kim I.

-

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) for providing the data used in this study.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Fig. 1.Framework of the ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health). Source: Finger et al. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34(5):429-38.

14

Fig. 2.Occupational health trajectory of a worker’s illness when the sickness benefit system does not function.

Fig. 3.Occupational health trajectory of a worker’s illness when the sickness benefit system functions properly.

Table 1.Conceptual definitions of “Malady”

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Malady |

Broad concept encompassing the shift from healthy to unhealthy state and that state itself |

|

Illness |

Unhealthy state perceived subjectively (e.g., mental illness) |

|

Disease |

Unhealthy state characterized by pathological processes deviating from the norm (e.g., infectious disease) |

|

Disorder |

Loss of certain bodily functions (e.g., neurological disorders) |

|

Disability |

Permanent, irreversible loss of function |

|

Sickness |

Unhealthy state verified or recognized externally, key to sickness benefit eligibility |

Table 2.Brief ICF core set for vocational rehabilitation

|

Code |

Title |

|

d155 |

Acquiring skills |

|

d240 |

Handling stress and other psychological demands |

|

d720 |

Complex interpersonal interaction |

|

d845 |

Acquiring, keeping, and terminating a job |

|

d850 |

Remunerative employment |

|

d855 |

Non-remunerative employment |

|

e310 |

Immediate family |

|

e330 |

People in positions of authority |

|

e580 |

Health services, systems, and policies |

|

e590 |

Labour and employment services, systems, and policies |

|

b130 |

Energy and drive functions |

|

b164 |

Higher-level cognitive functions |

|

b455 |

Exercise tolerance functions |

REFERENCES

- 1. Busse R, Blumel M, Knieps F, Barnighausen T. Statutory health insurance in Germany: a health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition. Lancet 2017;390(10097):882–97.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Lim SJ, Lee YG, Lee JM. An international comparison of sickness benefit programs. Health Soc Welf Rev 2021;41(1):61–80.

- 3. Kim SJ, Kim KT. What kind of support can sick workers get from their employers?: a study on social protections for sickness in US, Switzerland and Israel. Korea Soc Policy Rev 2019;26(1):3–33.

- 4. Park SK. Injury and sickness allowance system and issues in Japan: focusing on recent revisions and COVID-19 responses. Korean Soc Secur Law Assoc J 2022;11(1):1–49.

- 5. Kim KT, Lee SS. Comparative analysis of sickness benefits abroad and proposal for its introduction in Korea. Soc Welf Policy 2018;45(1):148–79.Article

- 6. Anner J, Schwegler U, Kunz R, Trezzini B, de Boer W. Evaluation of work disability and the international classification of functioning, disability and health: what to expect and what not. BMC Public Health 2012;12:470.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 7. Breivik E, Kristiansen E, Zanaboni P, Johansen MA, Oyane N, Bergmo TS. Suitability of issuing sickness certifications in remote consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed method study of GPs' experiences. Scand J Prim Health Care 2024;42(1):7–15.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers—A Synthesis of Findings across OECD countries. Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2011.

- 9. Broadbent A. Prediction, understanding, and medicine. J Med Philos 2018;43(3):289–305.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Hofmann B. On the triad disease, illness and sickness. J Med Philos 2002;27(6):651–73.ArticlePubMed

- 11. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Geneva, Germany: World Health Organization; 2001.

- 12. Henderson M, Glozier N, Holland Elliott K. Long term sickness absence. BMJ 2005;330(7495):802–3.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Soderberg E, Alexanderson K. Sickness certificates as a basis for decisions regarding entitlement to sickness insurance benefits. Scand J Public Health 2005;33(4):314–20.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 14. Finger ME, Escorpizo R, Glassel A, Gmunder HP, Luckenkemper M, Chan C, et al. ICF Core Set for vocational rehabilitation: results of an international consensus conference. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34(5):429–38.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Berardi C, Schut F, Paolucci F. The dynamics of international health system reforms: Evidence of a new wave in response to the 2008 economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic? Health Policy 2024;143:105052.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Waddell G, Burton AK, Kendall NA. Vocational Rehabilitation: What Works, for Whom, and When?. London, UK: TSO; 2008.

- 17. Escorpizo R, Finger ME, Glassel A, Cieza A. An international expert survey on functioning in vocational rehabilitation using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. J Occup Rehabil 2011;21(2):147–55.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 18. Whitaker SC. The management of sickness absence. Occup Environ Med 2001;58(6):420–4.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Pickles C, Holmes E, Titley H, Dobson B. Working Welfare: A Radically New Approach to Sickness and Disability Benefits. London, UK: Reform; 2016.

- 20. Escorpizo R, Brage S, Homa D, Stucki G. Handbook of Vocational Rehabilitation and Disability Evaluation: Application and Implementation of the ICF. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2014.

- 21. King R, Murphy R, Wyse A, Roche E. Irish GP attitudes towards sickness certification and the 'fit note'. Occup Med (Lond) 2016;66(2):150–5.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Foley M, Thorley K, Denny M. 'The sick note': a qualitative study of sickness certification in general practice in Ireland. Eur J Gen Pract 2012;18(2):92–9.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Wynne-Jones G, Mallen CD, Mottram S, Main CJ, Dunn KM. Identification of UK sickness certification rates, standardised for age and sex. Br J Gen Pract 2009;59(564):510–6.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 24. Kotze E. Employers' views on the fit note. Occup Med (Lond) 2014;64(8):577–9.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Wainwright E, Wainwright D, Keogh E, Eccleston C. The social negotiation of fitness for work: tensions in doctor-patient relationships over medical certification of chronic pain. Health (London) 2015;19(1):17–33.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Berglund E, Friberg E, Engblom M, Svard V. Physicians' experience of and collaboration with return-to-work coordinators in healthcare: a cross-sectional study in Sweden. Disabil Rehabil 2024;46(18):4120–8.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Hemmings P, Prinz C. Sickness and Disability Systems: Comparing Outcomes and Policies in Norway with Those in Sweden, the Netherlands and Switzerland. Paris, France: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2020.

- 28. Sturesson M, Bylund SH, Edlund C, Falkdal AH, Bernspang B. Quality in sickness certificates in a Swedish social security system perspective. Scand J Public Health 2015;43(8):841–7.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 29. Nilsing E, Soderberg E, Oberg B. Sickness certificates: what information do they provide about rehabilitation? Disabil Rehabil 2014;36(15):1299–304.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Chimed-Ochir O, Nagata T, Nagata M, Kajiki S, Mori K, Fujino Y. Potential work time lost due to sickness absence and presence among Japanese workers. J Occup Environ Med 2019;61(8):682–8.ArticlePubMed

- 31. Stone DA. Physicians as gatekeepers: illness certification as a rationing device. Public Policy 1979;27(2):227–54.PubMed

- 32. Marshall JM. Moral hazard. Am Econ Rev 1976;66(5):880–90.

- 33. Hall C, Hartman L. Moral hazard among the sick and unemployed: evidence from a Swedish social insurance reform. Empir Econ 2010;39:27–50.ArticlePDF

- 34. Johansson P, Palme M. Moral hazard and sickness insurance. J Public Econ 2005;89(9-10):1879–90.Article

- 35. Joo H, Hong J, Jung J. Projection of future medical expenses based on medical needs and physician availability. J Korean Med Sci 2025;40(24):e121.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 36. Kraft KB, Hoff EH, Nylenna M, Moe CF, Mykletun A, Ostby K. Time is money: general practitioners' reflections on the fee-for-service system. BMC Health Serv Res 2024;24(1):472.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 37. Hoff EH, Kraft KB, Moe CF, Nylenna M, Ostby KA, Mykletun A. The cost of saying no: general practitioners' gatekeeping role in sickness absence certification. BMC Public Health 2024;24(1):439.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 38. Thorstensson CA, Mathiasson J, Arvidsson B, Heide A, Petersson IF. Cooperation between gatekeepers in sickness insurance: the perspective of social insurance officers. A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:231.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 39. Bengtsson Bostrom K, Starzmann K, Ostberg AL. Primary care physicians' concerned voices on sickness certification after a period of reorganization: focus group interviews in Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care 2020;38(2):146–55.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 40. Gulbrandsen P, Hofoss D, Nylenna M, Saltyte-Benth J, Aasland OG. General practitioners' relationship to sickness certification. Scand J Prim Health Care 2007;25(1):20–6.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 41. Hoedeman R, Krol B, Blankenstein AH, Koopmans PC, Groothoff JW. Sick-listed employees with severe medically unexplained physical symptoms: burden or routine for the occupational health physician? A cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:305.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 42. Nilsen S, Werner EL, Maeland S, Eriksen HR, Magnussen LH. Considerations made by the general practitioner when dealing with sick-listing of patients suffering from subjective and composite health complaints. Scand J Prim Health Care 2011;29(1):7–12.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 43. Nam YH. Interaction between out-of-pocket maximum and indemnity health insurance. J Converg Cult Technol 2024;10(3):667–73.

- 44. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. Evaluation of the 2023 Korean Pilot Sickness-Benefit Programme and Development of Operational Strategies for the Full-Scale Scheme. Sejong, Korea: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2023.

- 45. Kang HC. Principles and conceptual framework for the introduction of Korean sickness benefit. Health Policy Manag 2021;31(1):5–16.

, Inah Kim2,*

, Inah Kim2,*

KSOEM

KSOEM

Cite

Cite