Mediation analysis of chronotype, sleep-related factors, and depressive symptoms among workers: a cross-sectional study

Article information

Abstract

Background

This study aimed to examine the impact of chronotype on depressive symptoms and explore the mediating effects of sleep quality, pre-sleep cognitive arousal, and social jetlag in a sample of wage earners.

Methods

A total of 3,917 waged workers were surveyed online in July 2022. Logistic regression and mediation analysis were used to assess the relationship between chronotype (morningness, intermediate, and eveningness) and depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire ≥ 5), and the mediating effects of Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale (PSAS). All analyses were adjusted for age, education level, income level, marital status, coffee consumption, alcohol consumption, physical activity, occupation, employment status, and working hours to calculate odds ratios (ORs).

Results

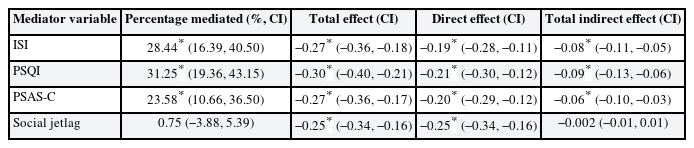

The chronotypes of all the participants were divided into morningness (4.7%), intermediate (93.5%), and eveningness (1.8%). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed an increased risk of depression in the eveningness chronotype (OR: 2.96; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.51, 5.86). Regarding the mediation analysis, ISI mediated 28.44% (95% CI: 16.39–40.5), PSQI for 31.25% (95% CI: 19.36, 43.15), and PSAS-Cognitive Score (PSAS-C) for 23.58% (95% CI: 10.66, 36.50) of the association between chronotype and depressive symptoms. However, social jetlag did not significantly mediate this relationship. (percentage mediated = 0.75%, 95% CI: −3.88, 5.39)

Conclusions

Evening chronotypes exhibit an increased risk of depressive symptoms, which ISI, PSQI, and PSAS-C partially mediated. This suggests that interventions to improve sleep quality and maintain adequate sleep habits may effectively prevent and treat depression in employees with an eveningness chronotype.

BACKGROUND

Depression is highly prevalent in the working population and significantly impacts productivity.12 However, the mechanisms underlying its development and maintenance among workers are poorly understood. Recent studies have focused on the role of chronotypes in the pathophysiology of depression.

The concept of “chronotype” refers to an individual's preference for sleep and wake times rooted in their inherent circadian rhythms. Typically categorized as morningness (early risers, most active in the morning) and eveningness (late sleepers, most active in the evening), an individual's chronotype can significantly influence their choice of activity times throughout the day.3 The influence of these varying chronotypes on mental health outcomes is a topic of ongoing research, particularly their potential role in the onset and persistence of depression.4

The association between evening chronotypes and increased risk of depressive symptoms or disorders has been highlighted in several studies, including findings among newly hired nurses in Korea5 and individuals in a Finnish birth cohort study.6 However, these associations were not statistically significant after adjusting for sleep variables or hours worked, suggesting that sleep-related factors play a role in the relationship between eveningness and poor work productivity.

Although the association between chronotypes and depression is well established, the underlying mediating factors remain poorly understood. Poor sleep quality is a purported potential mediator of the relationship between chronotypes and depression. Horne et al.7 (2019) and Chiu et al.8 (2017) reported that poor sleep quality is a potential mediator between eveningness and depressive symptoms.

However, there are conflicting researches regarding the mediating effect of sleep on the association between eveningness and depression.910 Müller et al.11 found that evening hours and subjective sleep quality were independent risk factors for increased depressive symptoms. Recent researches also indicating that evening sleep and insomnia are independent predictors of nonrelapse in individuals with depression.12 Consequently, the relationship between evening chronotypes and depression and the mediating role of sleep status remains inconclusive.

In addition to sleep quality, research points to the contribution of social and psychological factors, such as increased rumination and social jetlag, to the relationship between evening chronotypes and depressive symptoms.913 Nonetheless, research investigating the relationship between sleep-related sociopsychological factors, chronotype, and depressive symptoms remains limited, necessitating further epidemiological studies.

Despite the significant impact of depression on productivity, research on the association between chronotypes and depressive symptoms has primarily focused on the general population or individuals with depression, with limited studies specifically conducted in the context of the workforce. Existing epidemiological studies involving nurses and shift workers often lack applicability to the broader working population.14 This study aimed to investigate the relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms in the general working population in Korea and explore the mediators of this relationship. By investigating the potential mediation of sleep-related factors in the relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms, our study aimed to provide insights into developing interventions to reduce the risk of depression among workers with circadian rhythm disorders.

METHODS

Participants

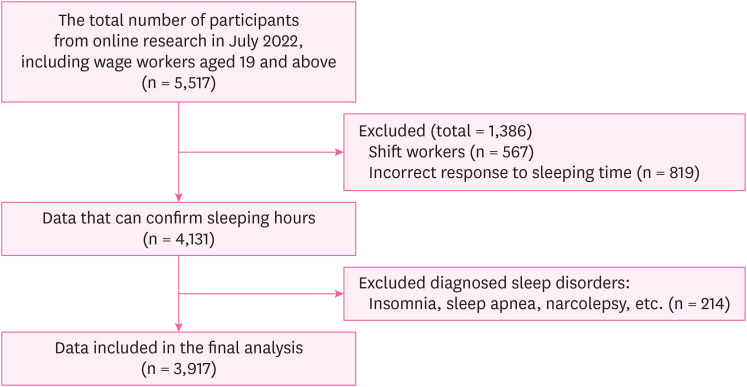

Participants were recruited in July 2022 using the online survey platform EMBRAIN. A total of 5,517 participants completed the initial screening process (wage earners aged 19 years and older), and those who met the following criteria were included: regular daytime work schedules, correct sleeping time, and no self-reported diagnosed sleep disorders. A total of 3,917 participants met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. A flowchart of the participants is shown in Fig. 1.

Measurements

Chronotype

Chronotypes were assessed using the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ),4 a self-reported questionnaire that measures an individual's preferred timing for sleep and activity. The participants were classified into three chronotype groups based on their MEQ scores: morning types (MEQ scores ≥ 18), intermediate types (MEQ scores of 12–17), and evening types (MEQ scores ≤ 11).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a self-report questionnaire that measures the severity of depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 measures the severity of depressive symptoms, with scores ranging from 0 to 27. PHQ-9 scores ≥ 5 were indicative of potential depressive symptoms. This cutoff was established to include a wide range of depressive symptoms, including early and mild symptoms, to identify individuals potentially at risk of developing depression.15

Sleep-related variables

Insomnia was evaluated using the Korean version of the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). The ISI comprises seven items, each scored on a scale of 0–4 points, resulting in a possible score range of 0 to 28 points. A total score exceeding 8 points indicated as the high-risk group for insomnia.16

Sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), a self-reported questionnaire that measures subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction,17 with a total possible score of 21 points, with a higher score indicating poorer sleep quality. Sleep quality was classified into three levels: "good" for scores < 5, "moderate" for scores of 5–10, and "poor" for scores ≥ 11.

Pre-sleep cognitive arousal was measured using the Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale (PSAS), consisting of eight items that assess the level of cognitive arousal before bedtime.18 A clinically relevant cut-off score ≥ 20 has been reported for the PSAS.19

Social jetlag was measured using the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire, consisting of 24 items that assess the discrepancy between the timing of biological rhythms and social schedules. The difference between mid-sleep on workdays and free days was used as a measure of social jetlag.13 The level of social jetlag was categorized as follows: "mild" (< 1 hour), "moderate" (1–2 hours), and "severe" (> 2 hours).

Covariates

Work-related variables were adjusted to minimize the potential influence of physical activity on the relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms. Work-related variables included job category (blue-collar: manual labor, white-collar: professional/clerical, pink-collar: service-oriented roles), job tenure (worked < 3 years or not), employment status (part-time; full-time), multiple job holdings (none; same field; different fields), and weekly working hours (number of hours during a typical day).

Sociodemographic variables, including sex (total sample), age, education, marital status, cohabitation status, smoking status, coffee drinking, alcohol consumption, income level, and physical activity, were collected through self-reported questionnaires and adjusted in this analysis.

Regarding income level, participants subjectively assessed their income, which was divided into six levels: "Very hard," "Hard," "Not enough," "Enough," "Sufficient," and "Very sufficient." Given the association between smoking status, insomnia, and mood regulation, participants were categorized into three groups20; “Current smoker,” “Ex-smoker,” and “None.” Coffee drinking were also categorized into three groups; “≤ 3 times/week,” “near-daily,” and “2–3 times/day.” Alcohol intake was assessed using the Five-Shot Questionnaire, which consists of five multiple-choice questions about alcohol use. Individuals were categorized as nondrinkers or dangerous drinkers based on their responses. A scores < 2.0 indicate alcohol abuse or dependency.21 The Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) was used to account for the potential influence of physical activity on the relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms.22 The total GPAQ score represents the sum of the total levels (MET.min/week) of activities at work, moving from one place to another, and leisure activities. The participants were categorized into three groups based on the total GPAQ scoring protocol: high, moderate, and low.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between the chronotypes and depressive symptoms, and the odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Model 1 represented the unadjusted analysis, whereas model 2 was adjusted for sociodemographic variables (i.e. age, sex, educational level, marital status, cohabitation status, smoking status, coffee consumption, alcohol consumption, income level, and physical activity). Model 3 further incorporated adjustments for work-related variables, including job category, tenure, employment status, multiple job holdings, and working hours. Because sex differences were identified in the relationship between chronotypes and depressive symptoms, all regression models were stratified by sex.23

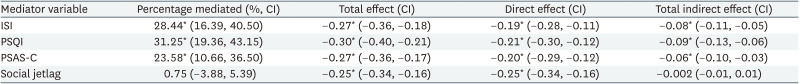

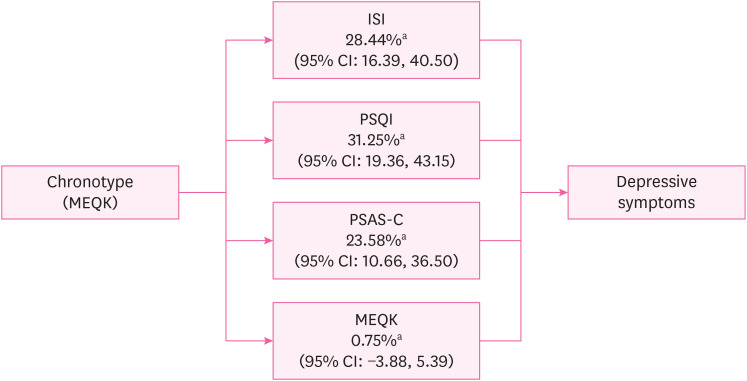

Furthermore, we investigated the mediating effects of ISI, PSQI, PSAS-Cognitive Score (PSAS-C), and social jetlag on the association between chronotype and depressive symptoms using the mediation analysis method proposed by Baron and Kenny24 (1986). The analysis calculated the total, direct, and indirect effects. A conceptual diagram of these mediating effects is shown in Fig. 2.

Conceptual diagram of sleep-related mediators in the relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms. This result was adjusted for sex, age, education level, marital status, cohabitation status, smoking status, coffee consumption, alcohol consumption, income level, physical activity, and work-related variables (job category, job tenure, employment status, multiple job holdings, and working hours).

ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSAS-C: Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale-Cognitive Score; MEQK: Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire Korean version; CI: confidence interval.

aPercentage mediated (%, CI).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Dong-A University of Korea (IRB number: 2-1040709-AB-N-01-202202-HR-017-06). All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

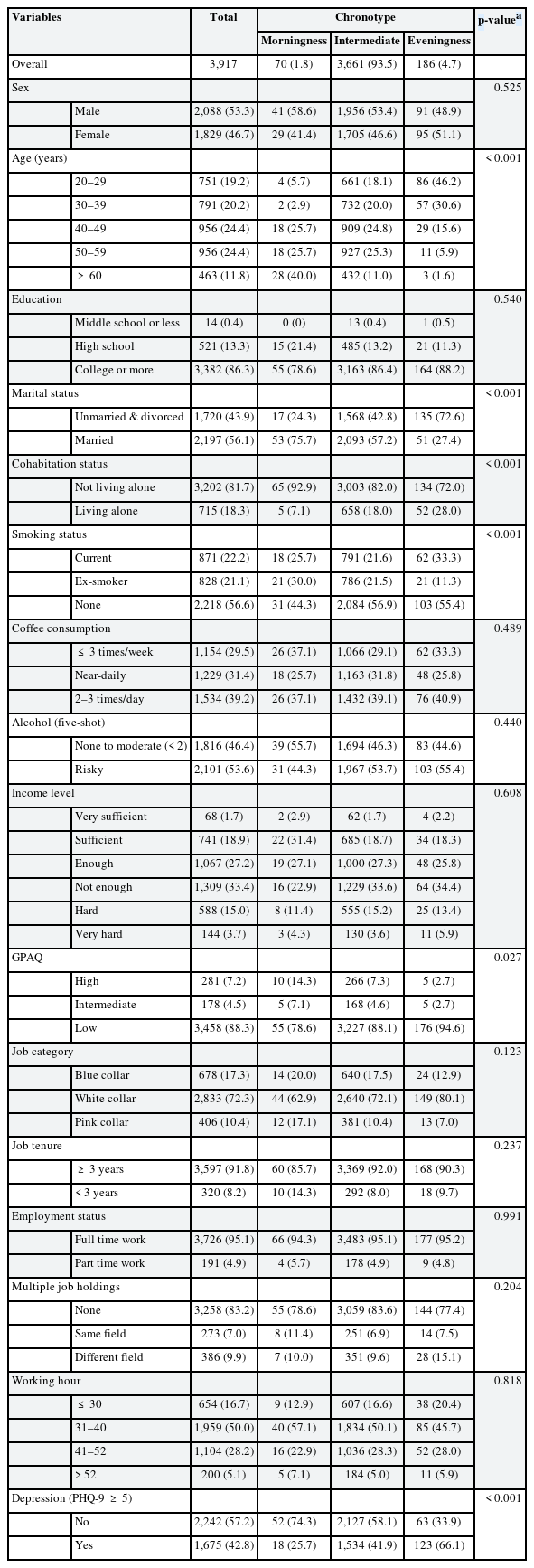

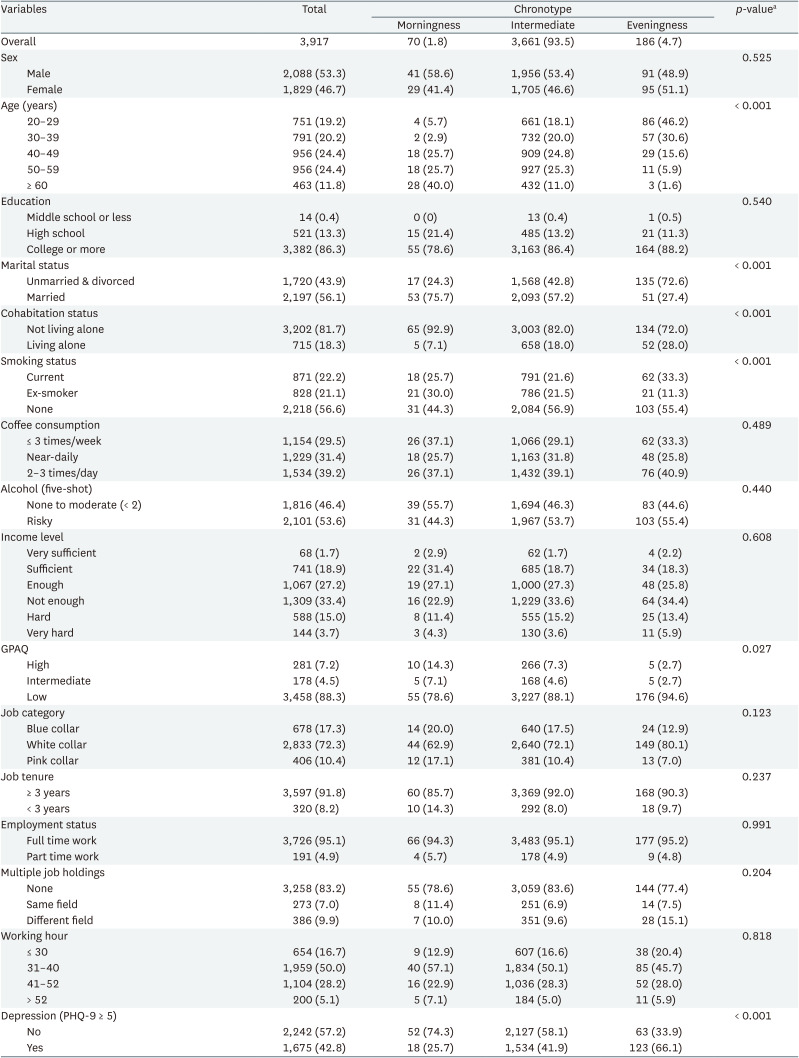

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics of the workers were analyzed according to their chronotypes (Tables 1 and 2). Of the 3,917 participants, 1.8% were morning-type, 93.5% intermediate, and 4.7% evening-type. The sex distribution did not significantly differ among chronotypes (p = 0.525). Average age was 43.4 ± 11.9, with morningness having the oldest mean (53.2 ± 10.8) and eveningness the youngest (33.8 ± 8.5). Eveningness participants were predominantly unmarried or divorced (72.6%) (p < 0.001). Activity levels (GPAQ) differed: morningness had the most active (14.3%) and eveningness the least (2.7%) (p = 0.027). Chronotypes showed no significant difference in education, alcohol use, income, job category, tenure, employment status, multiple jobs, or working hours. The depression variable showed a notable difference (p < 0.001); eveningness had the highest percentage of depression (66.1%) and morningness the lowest (25.7%).

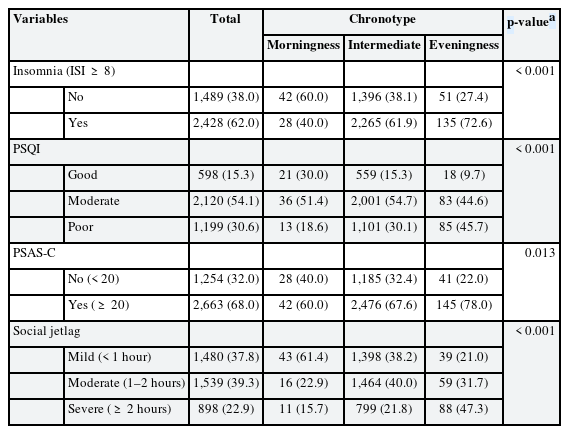

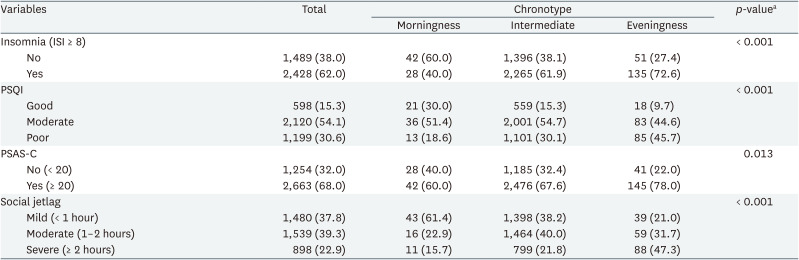

Table 2 shows baseline sleep characteristics. The proportion of participants who reported having trouble sleeping being highest in the eveningness group (72.6%) and lowest in the morningness group (40%) (p < 0.001). The PSQI also showed a significant difference between chronotypes, with the eveningness group having the largest percentage of participants with poor sleep quality (45.7%) and the morningness group having the lowest percentage (18.6%) (p < 0.001). In the PSAS-C, 78% of the eveningness group exceeded the cut-off point of 20, indicating high arousal, compared to 60% in the morningness group (p = 0.013). Social jetlag varied notably between chronotypes: 47.3% of eveningness had severe jetlag, compared to 15.7% in morningness (p < 0.001).

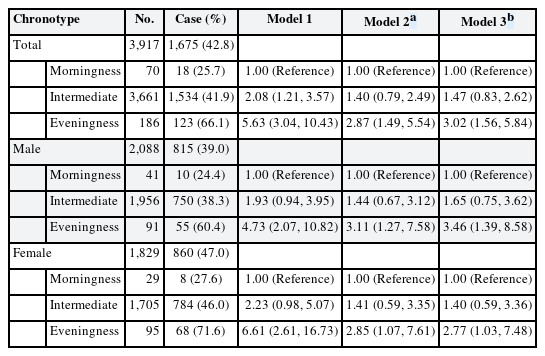

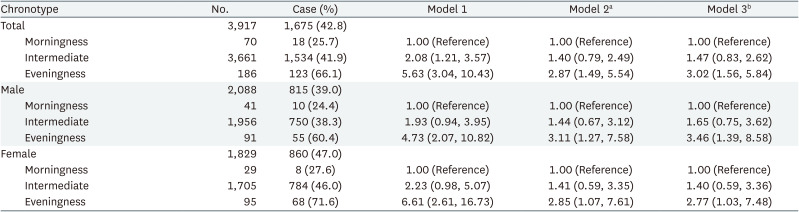

The multiple logistic regression analysis results are presented in Table 3. Compared to the morningness group, the eveningness group had a notably higher OR for depression across all models. In model 1 (crude model), the OR for eveningness was 5.63 (95% CI: 3.04, 10.43). In model 2, after adjustments, the ORs were 2.87 (95% CI: 1.49, 5.54) for eveningness and 1.40 (95% CI: 0.79, 2.49) for intermediate. Further adjustment for work-related factors in model 3 slightly attenuated the OR to 3.02 (95% CI: 1.56, 5.84) and 1.47 (95% CI: 0.83, 2.62) in the intermediate group.

In the sex-stratified analysis, the OR for depressive symptoms in the eveningness group was higher for both in model 1 (men: 4.73, 95% CI: 2.07, 10.82; women: 6.61, 95% CI: 2.61, 16.73). Adjustments in model 2 yielded ORs of 3.11 (95% CI: 1.27, 7.58) for men and 2.85 (95% CI: 1.07, 7.61) for women. Further adjustments in model 3 resulted in ORs of 3.46 (95% CI: 1.39, 8.58) for men and 2.77 (95% CI: 1.03, 7.48) for women.

The stratified analysis of sleep-related variables is presented in Supplementary Table 1. The insomnia group (ISI ≥ 8) and in the PSQI, evening chronotype workers displayed a higher OR for depressive symptoms in the crude model. However, upon adjustments in Model 2 and Model 3, the ORs showed non-significant CIs.

When evaluating the PSAS-C, evening chronotype workers in the "Normal" category had an OR that decreased in the following models. Yet, in the "Risk" group, there was a significant association in both model 2 with an OR of 2.68 (95% CI: 1.22, 5.85) and in model 3 with an OR of 2.72 (95% CI: 1.24, 5.97).

In social jetlag, evening chronotype workers in the "Mild" category registered notable ORs of 4.67 (95% CI: 1.62, 13.51) in model 2 and 5.43 (95% CI: 1.84, 15.99) in model 3. However, in the "Moderate" and "Poor" groups of social jetlag, the CIs were not significant.

Table 4 presents the results of the mediation analysis. The ISI, PSQI, PSAS-C, and social jetlag were included as potential mediators. After adjusting for sociodemographic and work-related variables, ISI, PSQI, and PSAS-C partially mediated the relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms. The mediating effect of ISI was 28.44% (95% CI: 16.39, 40.50), PSQI was 31.25% (95% CI: 19.36, 43.15), and PSAS-C was 23.58% (95% CI: 10.66, 36.50). Social jetlag did not significantly mediate the relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms, demonstrating a minimal mediating effect of only 0.75% (95% CI: −3.88, 5.39). The total indirect effect was negative for all four mediator variables, indicating that these variables partially mediated the negative relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms. However, the statistical significance of the total indirect effect of social jetlag was not confirmed, as the 95% CI ranged from −0.02 to 0.005, including zero within its range.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms among the general working population in Korea while also examining the mediating role of various sleep-related variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that individuals with an eveningness chronotype had significantly higher odds of experiencing depressive symptoms than those of individuals with a morningness chronotype, even after adjusting for potential confounding variables, such as sociodemographic factors and work-related characteristics. Furthermore, the mediation analysis results revealed that the relationship between chronotypes and depressive symptoms could be partially explained by sleep-related variables. However, social jetlag did not have a substantial mediating effect.

These results align with previous researches, indicating that individuals with eveningness chronotypes are more prone to experiencing depressive symptoms than those with morningness chronotypes.2526 Despite conflicting reports, compelling evidence suggests that eveningness reduces sleep quality, which directly impacts depression.

Another point of contention is whether the evening chronotype results from depressive symptoms or a potential causative factor. A meta-analysis in 2017 revealed no significant distinction in the relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms when comparing the results of patients with depression to those of the general population, suggesting that the evening chronotype could serve as a risk factor for depression. However, the mechanisms underlying this potential relationship are unknown.27 According to the vulnerability-stress hypothesis of depression, the interplay between psychological vulnerability factors (e.g., negative biases, preferential processing of negative content) and environmental stressors (e.g., bereavement, financial uncertainty) contributes to depression.28 Several studies have also associated eveningness with high neuroticism, depressive personality types, negative biases in emotion processing, and impaired emotion regulation in healthy individuals without a history of depression.92930 When these factors coincide with adversity, it can trigger depressive symptoms.25

One potential biological mechanism to explain the association between chronotype, sleep-related problems, and depression is the dysregulation of the circadian system. The circadian system regulates physiological processes, including the sleep-wake cycle and the release of hormones such as cortisol and melatonin, and its disruption in individuals with the eveningness chronotype may lead to sleep-related issues and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, potentially resulting in hypercortisolemia. This chain of events contributes to the onset and persistence of depressive symptoms.3132

Additionally, neurobiological research has revealed abnormalities in brain regions such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex among individuals with the eveningness chronotype involved in emotion regulation.2933 The current study expanded on these findings by stratifying potential mediating factors that may explain the relationship between chronotypes and depressive symptoms.

Our mediation analysis revealed that insomnia severity, sleep quality, and PSAS partially mediated the association between chronotype and depressive symptoms, suggesting that sleep-related problems commonly observed in individuals with the eveningness chronotype may contribute to an increased risk of depression. This reinforces the previously described idea that misalignment between the circadian rhythm and sleep-wake cycle, coupled with chronic insomnia, can impact mood and increase the risk of depression.

PSAS was identified as a partial mediator between chronotypes and depressive symptoms, with the higher PSAS-C group notably associating the evening chronotype with depressive symptoms in the stratified logistic regression analysis. Elevated pre-sleep cognitive arousal levels have been associated with poor sleep quality and an increased risk of depression. For instance, a study conducted during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy found that the evening chronotype was a specific predictor of PSAS-C, and higher PSAS-C was linked to poorer sleep quality.34 Furthermore, previous research assessing the psychometric properties of the PSAS showed correlations with anxiety and depression.18 However, the exact mechanism underlying this association remains unclear. One possibility is that the items used in the PSAS-C to assess persistent cognition reflect rumination. Rumination, a key cognitive process in mood disorders, may be prolonged due to a delay in circadian rhythm timing among individuals with the evening chronotype, potentially leading to the development of depression.3536 Antypa et al.9 (2017) also reported that rumination, worry, and hopelessness mediate the relationship between chronotype and depression. Most recently, Nowakowska-Domagała et al.37 (2022) reported that rumination mediated the relationship between poor sleep quality and increased depression. These findings can be attributed to the mechanisms involving a mismatch in circadian rhythms, which can result in chronic stress due to working at non-preferred times. This mismatch can lead to a surge in cortisol, a hormone that regulates the stress response, along with a decrease in the slope of cortisol concentrations, potentially affecting the morning effect. These alterations in cortisol dynamics may contribute to rumination and increase the risk of developing depression.38

While the ISI and the PSQI were not significant in the stratified logistic analysis, mediation analysis revealed their mediating role in the association between the chronotype and depressive symptoms. This suggests that the direct impact of chronotype on depressive symptoms may not be immediately evident among insomnia and PSQI, but the indirect path via the variables can be significant. Regarding social jetlag, while mild forms are perceived as near-normal with minimal disruption, the non-significant results in moderate and poor categories suggest either a threshold effect stabilizing its relationship with depressive symptoms or potential resilience among those experiencing persistent jetlag. However, even though the mild category correlated with depressive symptoms, the mediation effect was limited, indicating the need for further research to elucidate the dynamics between social jetlag, chronotype, and depressive symptoms.

While the biological and physiological mechanisms between chronotype and depressive symptoms have been widely studied, the political implications also need consideration. Chronotypes, directly related to productivity and well-being, can influence labor policies and workplace regulations. Recognizing the diverse sleep patterns and the mental health outcomes could encourage policymakers to advocate for flexible working hours, especially for those with eveningness chronotypes. Moreover, a creative strategy would involve integrating these findings into health campaigns and promotions. It's essential to educate both the general population and employers about the importance of aligning work schedules with an individual's inherent circadian rhythm. In contemporary labor context, with its irregular working hours, night shifts, and long working hour, it's crucial to align working schedules with individual’s circadian preferences. This alignment could lead not only to improved health outcomes but also to enhanced workplace productivity. Therefore, adapting work schedules to better match the circadian rhythms of employees could serve as a pivotal step toward improving both individual health and organizational performance.

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. While there is a possibility of reverse causation, whereby individuals with depressive symptoms may exhibit an evening chronotype, the impact of reverse causation bias is likely minimal, given the genetic influence and stability of the chronotype.39404142 Furthermore, this study intentionally excluded shift workers, thereby reducing possible bias from daily light exposure. Nevertheless, future studies with longitudinal designs are necessary to conclusively determine the directionality of the observed associations. Second, the reliance on online surveys and convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader population. The higher prevalence of depressive symptoms and the proportion of white-collar workers in the study population compared to the general population of South Korea could have induced selection bias.4344 Moreover, the survey was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced the prevalence of depressive symptoms.45 The proportion of evening chronotypes was also significantly lower than that in the general Korean population (15.4% vs. 4.8%).23 However, this study focused specifically on wage earners and differed from the sample of the broader population surveyed in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which includes approximately 40% of the population without a job. Third, the survey did not capture specifics about the participant's industry or their position within the company. Fourth, there could be various other mediating factors (i.e. anxiety, screen time, etc), but our data did not encompass enough information to include these variables. Lastly, the assessments of chronotypes, depressive symptoms, and insomnia relied on self-reported questionnaires. The use of the dim light melatonin onset technique to determine the timing of melatonin secretion in the evening under low-light conditions may provide more reliable clinical measurements.46

CONCLUSIONS

The eveningness chronotype may be associated with a higher risk of depressive symptoms among workers, partially mediated by sleep-related variables. These findings necessitates workplace interventions, particularly focusing on sleep hygiene and flexible scheduling, to support those with the eveningness chronotype. Further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms underlying these associations and identify effective interventions for promoting healthy sleep and mental health among workers.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute for providing the raw data from the 6th Korean Working Conditions Survey.

Notes

Funding: This research is supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022R1F1A1066498).

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Kang MY.

Data curation: Cho SS.

Formal analysis: Kim SY.

Validation: Kang MY.

Visualization: Kim SY.

Writing - original draft: Kim SY, Kim HJ.

Writing - review & editing: Cho SS, Park MY, Kang MY.

Abbreviations

CI

confidence interval

COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

GPAQ

Global Physical Activity Questionnaire

IRB

Institutional Review Board

ISI

Insomnia Severity Index

MEQ

Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire

OR

odds ratio

PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

PSAS

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

PSAS-C

PSAS-Cognitive Score

PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

References

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Table 1

Odds ratios (95% confidence interval) of chronotype for depressive symptoms among workers (stratified by sleep-related variables)