The effect of long working hours on developing type 2 diabetes in adults with prediabetes: The Kangbuk Samsung Cohort Study

Article information

Abstract

Background

Long working hours are known to account for approximately one-third of the total expected work-related diseases, and much interest and research on long working hours have recently been conducted. Additionally, as the prevalence of prediabetes and the high-risk group for diabetes are increasing worldwide, interest in prediabetes is also rising. However, few studies have addressed the development of type 2 diabetes and long working hours in prediabetes. Therefore, the aim of this longitudinal study was to evaluate the relationship between long working hours and the development of diabetes in prediabetes.

Methods

We included 14,258 prediabetes participants with hemoglobinA1c (HbA1c) level of 5.7 to 6.4 in the Kangbuk Samsung Cohort Study. According to a self-reported questionnaire, we evaluated weekly working hours, which were categorized into 35–40, 41–52, and > 52 hours. Development of diabetes was defined as an HbA1c level ≥ 6.5%. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the development of diabetes were estimated using Cox proportional hazards analyses with weekly working 35–40 hours as the reference.

Results

During a median follow-up of 3.0 years, 776 participants developed diabetes (incidence density, 1.66 per 100 person-years). Multivariable-adjusted HRs of development of diabetes for weekly working > 52 hours compared with working 35–40 hours were 2.00 (95% CI: 1.50–2.67). In subgroup analyses by age (< 40 years old, ≥ 40 years old), sex (men, women), and household income (< 6 million KRW, ≥ 6 million KRW), consistent and significant positive associations were observed in all groups.

Conclusions

In our large-scale longitudinal study, long working hours increases the risk of developing diabetes in prediabetes patients.

BACKGROUND

Prediabetes is defined as an intermediate-dysregulation state of hyperglycemia with glucose levels above normal but below the diagnostic threshold for diabetes. People with prediabetes is at high-risk for developing of type 2 diabetes mellitus (diabetes).1 The definition and screening criteria for prediabetes differ between guidelines published by different institutions; hence, prediabetes prevalence estimates vary. However, despite these differences, it is clear that its prevalence has increased rapidly.2 Prediabetes is not only a remarkable risk factor for diabetes but is also considered as an independent, dangerous metabolic state after several studies have shown that it is associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease,3 retinopathy,4 neuropathy,5 and cardiovascular disease,6 which are traditionally considered complications of diabetes. Several studies have confirmed the importance of interventions in individuals identified with prediabetes.78910 Given the increasing prevalence and many pathologies, it is necessary to identify modifiable risk factors and prevent the onset of diabetes from a public health and clinical standpoint.

In South Korea, the average annual working hours per worker is 1,908 hours in 2020, which is one of the highest among OECD countries.11 Long working hours increase the risk of various adverse health outcomes. Several studies have shown that long working hours increase the risk for developing negative health outcomes such as obesity,12 hypertension,13 stroke and coronary heart disease,14 non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, 15 sleep,16 occupational injuries17 and so on. Similar to many other health outcomes, long working hours can play a crucial role in glycemic control and the development and progression of diabetes in Koreans, especially in high-risk groups, such as those with prediabetes. Much interest and research on long working hours has been recently conducted, but few longitudinal studies have addressed the relationship between prediabetes and long working hours. Therefore, this longitudinal study aimed to assess the relationship between long working hours and the development of diabetes in adults with prediabetes.

METHODS

Study population

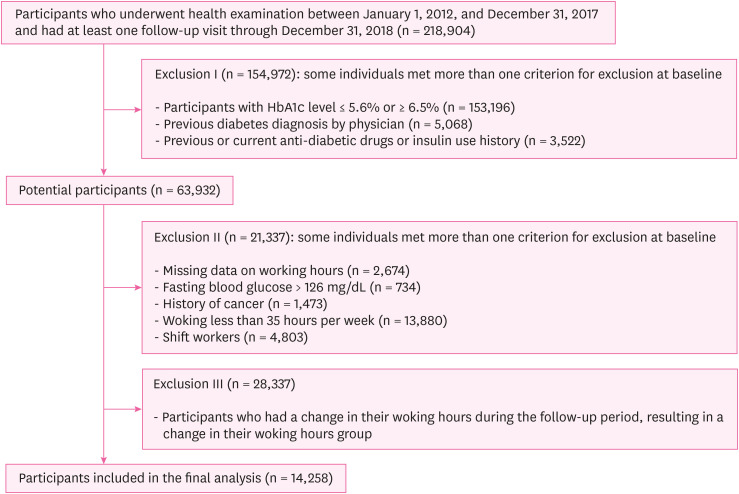

The Kangbuk Samsung Cohort Study is a study on South Korean men and women aged at least 18 years who underwent a comprehensive annual or biennial health examination at the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Total Healthcare Center in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea. More than 80% of the examinees were employees of various companies and local governmental organizations and their spouses. The present study included a total of 218,904 participants who underwent comprehensive health examinations from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2017, and had undergone at least one other screening examination before December 31, 2018. We selected prediabetes patients with an hemoglobinA1c (HbA1c) level of 5.7%–6.4%, except those who previously had been diagnosed with diabetes by a doctor and those who had previously used anti-diabetic drugs or insulin (n = 63,932). Among potential 63,932 participants, we excluded 21,337 participants who had any of the following conditions at baseline: missing data regarding working hours (n = 2,674); fasting blood glucose > 126 mg/dL (n = 734); self-reported history of cancer (n = 1,473); working less than 35 hours per week (n = 13,880); shift workers (n = 4,803). We regarded workers who worked for less than 35 hours a week as part-time. We excluded part-time and shift workers to minimize work-schedule-biased health effects. In addition, participants who experienced a change in their working hours during the follow-up period, resulting in a change in their working hours group, were excluded (n = 28,337). Finally, 14,258 individuals were selected as participants for this study (Fig. 1).

Working hours

Based on the Labor Standards Act, the study subjects were divided into three groups based on working hours: 35–40, 41–52, and > 52 hours per week. In South Korea, adult working hours should not exceed 40 hours per week, and 12 additional hours per week are permitted if agreed between parties. Working on weekends was not subject to regulation until 2018; therefore, if workers worked on a Saturday or Sunday, they could legally work more than 52 hours per week.18 Additionally, working hours of adolescents should not exceed 35 hours per week (five additional hours per week are allowed with workers’ agreement). Based on this standard, we evaluated the working hours using a self-reported questionnaire. Weekly working hours were assessed based on the following question: “How many hours did you work in one week, on average, in your job for the past year, including overtime?”

Measurement of HbA1c and definition of prediabetes and development of diabetes

HbA1c levels were measured using an immunoturbidimetric assay with a Cobra Integra 800 automatic analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Participants were identified as having prediabetes if they had an HbA1c level between 5.7% and 6.4%. An HbA1c level ≥ 6.5% at follow-up was defined as the development of diabetes. HbA1c is considered to be a more reliable test for impaired glucose homeostasis than fasting blood glucose.2 HbA1c has several advantages over fasting blood glucose, including greater convenience (since fasting is not required) and less intra-individual variation.19 Our participants were individuals who came for a health check-up and were informed to fast more than 8 hours prior to visiting the hospital, but we used HbA1c to rule out the possibility of non-fasting.

Measurement of variables

Data on age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, regular exercise frequency, marital status, education level, medication for hypertension or dyslipidemia, and history of cancer were collected using self-administered questionnaires. Blood pressure, height, and weight were measured by trained nurses. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, which is the proposed cut-off for the diagnosis of obesity in Asians. Blood samples were collected after fasting for at least 8 hours. Clinical chemistry parameters, such as fasting glucose, and HbA1c, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels were measured. Insulin resistance was assessed using the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) equation as follows: fasting insulin (μU/mL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/405.20 Smoking status was categorized as currently smoking or not. Alcohol consumption status was categorized as heavy consumption or not. Heavy alcohol consumption was defined as ≥ 20 g/day for women and ≥ 30 g/day for men.2122 Exercise habits were evaluated using the following question: “Frequency of vigorous leisure-time physical activity per week.” Regular exercise was defined as exercising three or more times per week. A high education level was defined as a college graduate or higher. Monthly household income was divided into eight categories ranging from less than 0.5 million Korean won (KRW) per month to more than 6 million KRW per month. Among each category, a household income of ≥ 6 million per month was the highest. We defined 6 million KRW as a high household income and conducted a subgroup analysis based on this to make the ratios of the two groups similar.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the study participants were presented according to their weekly working hours. The primary endpoint was the development of diabetes, defined as an HbA1c level ≥ 6.5%. Participants were followed from the baseline visit to the visit wherein diabetes was diagnosed or to the last available follow-up before December 31, 2018. We calculated person-years from the date of the baseline examination to the date of the first development of diabetes at the follow-up examination or the date of the last examination.

Incidence density was calculated as the number of incident cases divided by person-years during the follow-up period. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed to assess the association between working hours and the development of diabetes. In model 1, we adjusted for age and sex. In model 2, we further adjusted for alcohol consumption, smoking, regular exercise, medication for hypertension or dyslipidemia, BMI, HOMA-IR and hsCRP. In model 3, we adjusted for social factors such as education, marital status, and household income, in addition to model 2. To explore the mechanism underlying the observed associations between working hours and the development of diabetes, subgroup analysis was performed by age (< 40 years vs. ≥ 40 years), sex (women vs. men), and household income (< 6 million KRW vs. ≥ 6 million KRW). For all p-values (2-sided), < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital approved this study (IRB No. KBSMC 2021-10-034) and waived the requirement for informed consent. This was due to the use of anonymized data that were routinely collected as part of a health checkup program.

RESULTS

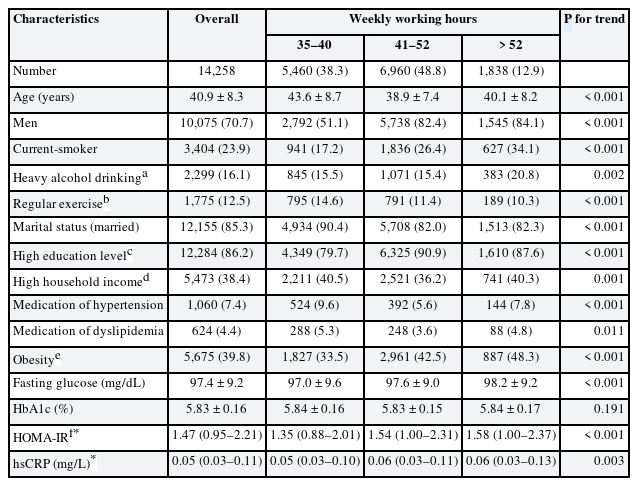

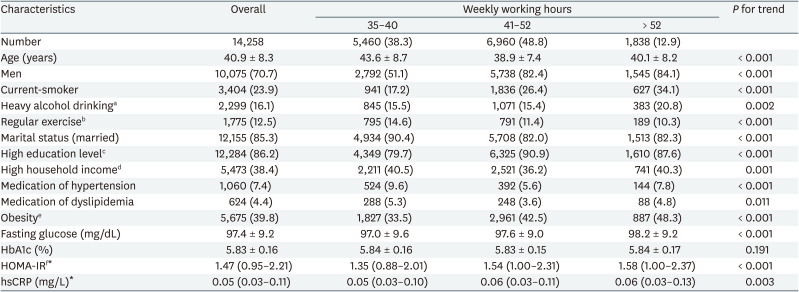

Of the study participants, 5,460 worked 35–40 hours per week, and those who worked 41–52 hours and > 52 hours totaled 6,960 and 1,838, respectively. The mean age of study participants at baseline was 40.9 ± 8.3 years and 70.7% were men. Weekly working hours were positively associated with men, current smoking status, heavy alcohol consumption, high education levels, obesity, fasting glucose levels, HOMA-IR and hsCRP levels, whereas they were inversely associated with age, regular exercise, marital status, and hypertension or dyslipidemia medication (Table 1).

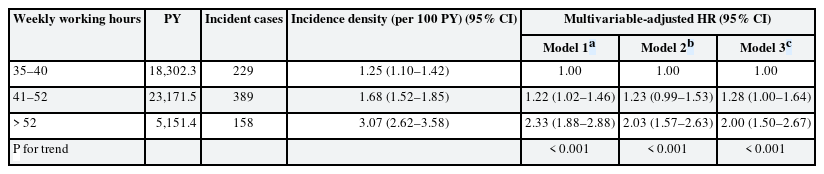

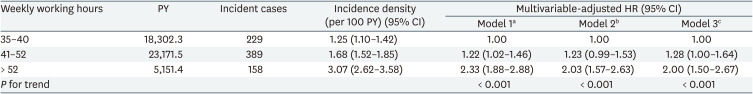

During 46625.2 person-years of follow-up (median, 3.0 years), total of 776 participants developed diabetes (incidence density, 1.66 per 100 person-years). Participants with longer working hours had a higher incidence of diabetes. The age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) (95% confidence interval [CI]) for the development of diabetes in the longest working hours group compared to the reference group was 2.33 (1.88–2.88). Finally, in addition to model 2, after adjusting for social factors, such as education, marital status, and household income in model 3, the association did not change (HR: 2.00; 95% CI: 1.50–2.67) (Table 2).

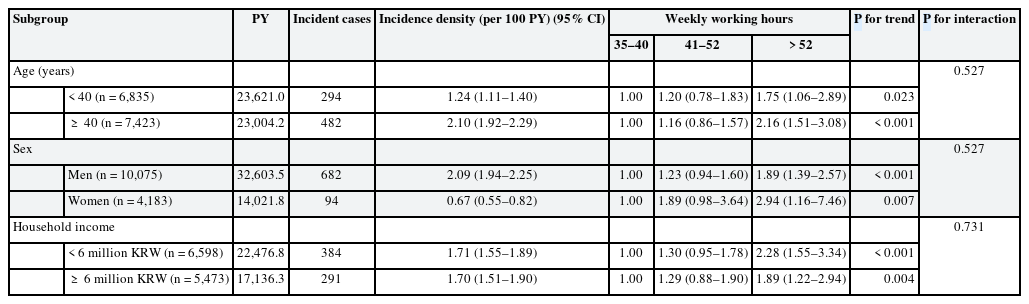

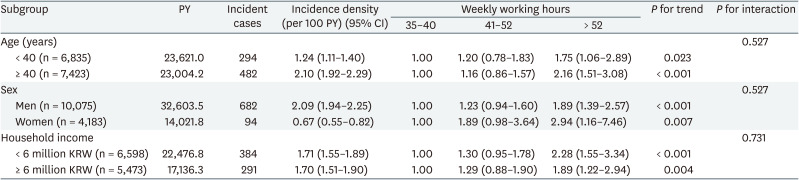

In subgroup analyses by age (< 40 years vs. ≥ 40 years), sex (men vs. women), and household income (< 6 million KRW vs. ≥ 6 million KRW), consistent and significant positive associations in all groups were observed. In particular, women with prediabetes exposed to long working hours were 2.94 times more likely to develop diabetes (HR: 2.94; 95% CI: 1.16–7.46). And the group with a household income less than 6 million KRW also showed a high risk of developing diabetes (HR: 2.28; 95% CI: 1.55–3.34). The association between long working hours and the development of diabetes did not differ by age, sex, and household income (Table 3). In addition, long working hours showed a significant association with prediabetes regardless of shift work (Supplementary Table 1).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated whether working hours are an independent risk factor for the development of diabetes in patients with prediabetes. In our large-scale cohort study, long working hours had a significant effect on diabetes incidence in adults with prediabetic state at baseline. Participants who worked more than 52 hours per week had a significantly higher risk of diabetes compared to reference group, participants who worked 35–40 hours per week.

As our study subjects were relatively young, had a low prevalence of underlying diseases, and underwent medical checkups every year or two, we tried to avoid healthy worker bias in relation to developing diabetes. Therefore, in model 3, we adjusted for social factors such as education, marital status, and household income. As a result, the positive association between weekly working hours and diabetes incidence weakened slightly, but it was still maintained.

The exact mechanisms involved are not clear yet. Several possible mechanisms have been proposed relating to how long working hours increase the risk of diabetes in prediabetes. First, longer working hours may lead to changes in lifestyle behaviors that decrease exercise and increase smoking or alcohol consumption,2324 which are known as risk factors for diabetes.2526 Decreased regular exercise can result in body weight gain, and body weight control is important to prevent the progression of prediabetes to diabetes.27 After adjusting for lifestyle variables such as alcohol consumption, smoking and regular exercise, the association was slightly weakened in this study. However, the statistical significance was still maintained, suggesting that variables other than lifestyle should be considered. Second, the more working hours, the higher the likelihood that workers will not be able to eat regularly. The time of the day chosen for food intake affects human energy expenditure and metabolic response to meals.28 Therefore, long working hours that lead to the omission of breakfast along with a late-night dinner could result in poor glycemic control in prediabetes. In the US study, men who did not consume breakfast had a 21% higher risk of diabetes than men who consumed breakfast, even after adjusting for known risk factors for diabetes, including BMI.29 Late-night dinner (later than 8 pm) was shown to be independently associated with poor glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients.30 Third, long working hours could cause increased psychosocial stress.31 Repetitive stress could lead to the dysregulation of glucose metabolism through neuroendocrine mechanisms (catecholamine, glucocorticoids, and inflammation).32 One study showed that various pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers were associated with progression from prediabetes to diabetes, suggesting that inflammation could be a useful target in preventing the progression of prediabetes to diabetes.33

We confirmed that the positive association did not change in all groups through subgroup analyses according to age (< 40 years old vs. ≥ 40 years old), sex (men vs. women), and household income (< 6 million KRW vs. ≥ 6 million KRW) (Table 3). According to the Korea Diabetes Association, diabetes screening tests are recommended annually for adults aged over 40 years or adults aged over 30 years with risk factors.34 In addition, according to the Diabetes Fact Sheet in Korea 2020, the prevalence of diabetes in both men and women increases with increasing age, and the prevalence of diabetes in men exceeds 10% in their 40s and in women in their 50s.35 Therefore, we observed the development of diabetes with age based on the age of 40 years. Notably, we found that the HRs were more pronounced in women than men. It suggests that women are more vulnerable to the effects of long working hours than men. A recent prospective study in Brazil showed that job stress was associated with the risk of prediabetes and diabetes only among women. In addition, it showed that highly educated women with job stress were four times more likely to develop diabetes.36 This study showed similar to the finding that women have a higher HR than men in our study, which consisted mostly of highly educated people. Moreover, according to a recent study using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, long working hours (> 52 hours per week) were associated with poor glycemic control (HbA1c > 9%) compared to shorter working hours (≤ 40 hours per week) only among elderly (≥ 60 years of age) female workers with diabetes.37 Our study shows a unique strength that extends the results of this cross-sectional study to longitudinal-cohort study.

In contrast to our findings, a meta-analysis of 23 cohort studies on working hours and the incidence of type 2 diabetes identified lower socioeconomic status as a significant risk factor.38 It showed that long working hours (≥ 55 hours per week) are related to the risk of diabetes in workers with lower socioeconomic status. Our study has extended results showing that long working hours are a significant risk factor, even in high-household income groups.

Meanwhile, a previous Japanese study in which race, sample size, duration of follow-up, and the covariates used for adjustment were similar to ours, reported that persistently long working hours were not associated with the development of diabetes in prediabetes.39 Healthy worker effect was presented as a reason for the null findings. However, compared to this Japanese study, the subjects of in our study were younger, baseline conditions such as smoking and HbA1c levels were better, and the conversion rate from prediabetes to diabetes was lower (5.4% vs. 8.9%). And risk of working hours for the development of diabetes was observed only in our study.

The present study had several strengths. First, relatively long working hours (compared with other countries) provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the association between working hours and the development of diabetes in prediabetes. Based on meta-analysis, shift work was associated with an increased risk of diabetes,40 and the risk of diabetes associated with long working hours differed by shift work schedules.41 Since shift workers and part-time workers (less than 35 hours per week) were excluded in this study, we focused on the effect of working hours only. The same analysis was additionally performed in this study, including shift workers. As a results, long working hours showed a stronger negative health effect on shift workers (Supplementary Table 1). Second, our study population consisted of apparently healthy, highly educated young and middle-aged Korean men and women. Other variables were well controlled, and working hours were considered appropriate to obtain consistent results. Moreover, a recent community-based cohort study in older adults showed that regression to normoglycemia or death was more frequent than diabetes progression among older adults with prediabetes. These findings suggest that prediabetes may not be a strong diagnostic entity in the older adult groups.42 Because our study consisted of young and middle-aged men and women, this study is appropriately designed to assess the progression of diabetes in individuals with prediabetes. Finally, our study ensured an accurate estimate of HbA1c levels with standardized laboratory procedures.

However, this study had several limitations. First, since this study collected working hour data using a questionnaire, it may have self-reported bias. Second, the differences between occupations and occupational characteristics were not adequately considered in this study. Since diabetes is a disease that is affected by physical activity, not only the working hours but also the occupational type and intensity could be one of the important factors in the progression of diabetes. The differences between the type and intensity of work should be fully examined in future studies. Third, the conversion rate from prediabetes to diabetes is low in this present study. While estimates vary from study to study, approximately one-fourth of individuals with prediabetes will develop diabetes within 3–5 years.43 However, in our study, a total of 5.4% developed diabetes during the median 3.0 years follow-up. The healthy worker effect may have played a role in this conversion rate. This effect may have affected the conversion rate, but it did not seem to have affected the present positive conclusion. Moreover, it appears that the follow-up period was not too short to observe the progression of prediabetes to diabetes. To examine the effect of working hours on diabetes development, it takes a long time to observe healthy adults with normal HbA1c levels. Our study observed prediabetes, and accordingly, it was possible to observe the development of diabetes in a relatively short time. According to the American Diabetes Association, more than two-thirds of individuals with prediabetes eventually progress to diabetes within their lifetime.1 For more accurate analysis, future studies should be conducted with longer follow-up periods to possibly uncover the exact mechanisms of the effects of long working hours on the development of diabetes.

As with other diseases, it is very important to recognize and intervene in modifiable risk factors for prediabetes, a high-risk group for diabetes. Our study is meaningful in that it identified a novel and modifiable risk factor called long working hours. Our results suggest that it is not only important to reduce long working hours but also that interventions such as occupational health care during working hours is required in prediabetes.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our cohort study showed that long working hours were positively associated with the development of diabetes in people with prediabetes. In particular, the positive association did not change in any subgroup analyses by age, sex, and household income. Additional longitudinal studies are needed to determine the mechanism of the progression from prediabetes to diabetes due to long working hours.

Notes

Funding: This research has been supported by the Korean Society of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (KSOEM) to assist a small research group.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions:

Conceptualization: Lee WC.

Investigation: Lee WC, Lee YS, Seo EH, Mun EC, Kim DH.

Methodology: Lee WC, Lee YS, Seo EH, Jeong YS, Lee JH.

Supervision: Jeong JS.

Writing - original draft: Seo EH.

Writing - review & editing: Lee WC.

Abbreviations

BMI

body mass index

CI

confidence interval

HbA1c

hemoglobinA1c

HOMA-IR

homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

HR

hazard ratio

hsCRP

high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

References

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Table 1

Hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) for development of diabetes in prediabetes by weekly working hours according to type of work schedule