Effect of job satisfaction on depression after adjusting for satisfaction with other life domains

Article information

Abstract

Background

Studies on the association between job satisfaction and depression have often been reported. However, no study has examined how job satisfaction impacts depression while considering satisfaction with other aspects of life. In this study, we evaluated the effect of job satisfaction on depression after adjusting for satisfaction with other domains of life.

Methods

We used data from the 16th wave of the Korean Welfare Panel Study. A total of 3568 current employees without depression who completed a survey were included. Depression was measured using the abbreviated version of the CES-D scale. Various types of satisfaction, including job satisfaction, were measured using single-item questions and a 5-point Likert scale. The association between job satisfaction and depression after considering satisfaction with other life domains was analyzed using a multiple logistic regression model.

Results

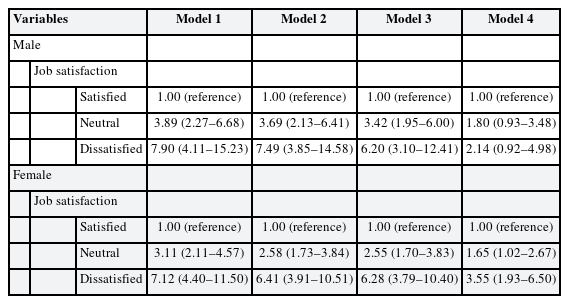

Crude models showed a significant association between job satisfaction and depression in males (odds ratio [OR]: 7.90; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.11–15.23) and females (OR: 7.12; 95% CI: 4.40–11.50). When adjusted for sociodemographic factors, health-related factors, and work-related factors, the association remained significant in males (OR: 6.20; 95% CI: 3.10–12.41) and females (OR: 6.28; 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.79–10.40). However, when satisfaction with other life domains was included, the association remained significant only in females (OR: 3.55; 95% CI: 1.93–6.50).

Conclusions

This study shows an association between job satisfaction and depression in Korean employees. However, when satisfaction with other life domains was considered, this association remained significant only in women. Regular screening of job satisfaction should be considered as a means of preventing and managing depression among female employees.

BACKGROUND

Depression is a mood disorder that manifests as a chronic mood decline, feelings of despair, and diminished interest,1 resulting in varying degrees of quality of life and functional impairment.2 Depression is a common illness, with an estimated global prevalence of 5.0% among adults,3 and it has been predicted that depression will become the leading cause of morbidity by 2030.4 In South Korea, approximately 15% of the population is expected to go through at least one episode of depression in their lifetime.5 In the future, it is anticipated that the social costs of depression will increase, which highlights the need for greater focus and effective coping strategies. Depression is influenced by various factors such as genetic predisposition, age, socioeconomic status, educational level, marital status, and life satisfaction, but is affected by occupational factors. High job demands, low job control, effort-reward imbalance, low relational justice, low procedural justice, role stress, harassment, and low social support in the workplace are all potential risk factors for depression.6

Job satisfaction is a subjective measure that stems from an individual's recollection of past job experiences.7 Various factors such as work environment, colleagues, and the opportunity to demonstrate one's expertise can influence job experience. Thus, job satisfaction provides a measure of how satisfied individuals are with their jobs,8 reflects overall feelings, and indicates whether attitudes to work are positive or negative.9 Therefore, if job satisfaction is low, employees are likely to harbor negative emotions towards work. Furthermore, job satisfaction is closely related to mental health issues such as anxiety, burnout, and depression.10 Many existing studies report a significant relationship between job satisfaction and depression. Notably, a cross-sectional study conducted on Chinese adults aged 35–60 concluded that increasing job satisfaction was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms,11 and a study that tracked Japanese civil servants for one year revealed that job dissatisfaction predicted the occurrence of short-term depression.12 Furthermore, a meta-analysis conducted on Chinese migrant workers revealed an association between job satisfaction and depressive symptoms.13

Although job satisfaction is important, satisfaction with other life domains can also influence depression. Research has revealed that health satisfaction is a predictor of depressive symptoms among the elderly.14 Furthermore, it has been reported that satisfaction with family relationships is an important predictor of depressive symptoms and that this relation depends on gender, age, and marital status.15 A study conducted on 155 female full-time workers in the southeastern United States revealed a relationship between leisure satisfaction and mental health,16 and a recent cohort study conducted on middle-aged Australian women revealed that satisfaction with social relationships is associated with many morbidities, including eleven chronic conditions such as anxiety and depression.17

Since most people spend approximately one-third of their lives at work until retirement, it might be expected that job satisfaction importantly influences depression and that an understanding of the impact of job satisfaction on depression might facilitate the development of interventions that effectively prevent depression in the workplace. While previous research has revealed a strong association between job satisfaction and depression, few study has yet assessed the impact of job satisfaction on depression while considering satisfaction in other life domains. The main purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of job satisfaction on depression while considering satisfaction with other life domains.

METHODS

Study design and participants

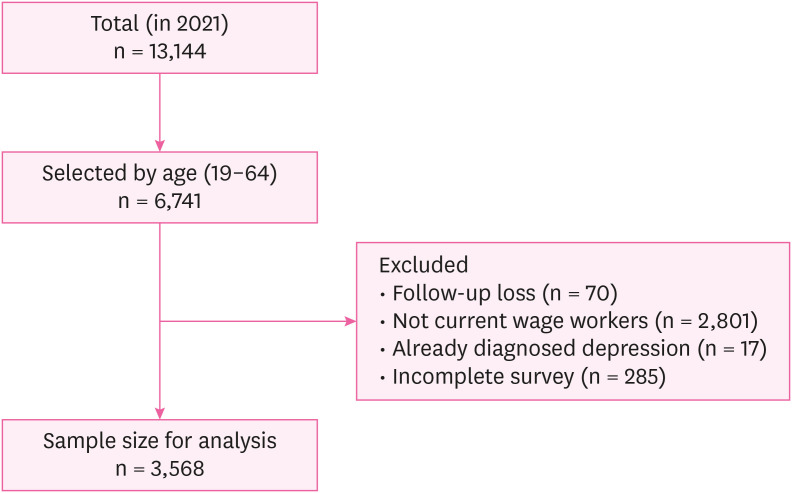

In this cross-sectional study, we evaluated the impact of job satisfaction on depression using data from the 16th wave of the Korean Welfare Panel Study, which has been conducted annually since 2006. Surveyors visited panel households in person, conducted direct interviews, and recorded responses. The 16th wave of the survey was conducted in 2021 and included 13,144 individuals from 6,240 households. In this study, we focused on 6,741 adults aged 19–64 among these 13,144 individuals. Of these 6,741 adults, the following were excluded: 70 with missing questionnaires, those not currently employed, self-employed, employers, or unpaid family workers, 17 with a diagnosis of depression, and 285 who did not provide complete responses to CES-D or satisfaction questionnaires. As a result, 3,568 individuals were selected as study participants (Fig. 1).

Depression

Depression was assessed using the abbreviated version of the CES-D scale. The CES-D is a validated tool used to measure the level of depressive symptoms experienced by members of the general population during the previous week. In panel surveys, there is a tendency to prefer the abbreviated CES-D scale over the original version, as the 20-item CES-D scale can be burdensome when surveying large, diverse subpopulations.18 In the 16th wave of the Korean Welfare Panel Study, the abbreviated version of the CES-D, also known as the Iowa form, was used. This survey consists of 11 self-reporting items (questions) that address perceptions of depression based on an individual’s psychological state over the previous week. Individuals answered each question ‘rarely’ (< 1 day per week), ‘sometimes’ (1–2 days per week), ‘often’ (3–4 days per week), or ‘most of the time’ (≥ 5 days per week) and these responses were scored from 0 to 3, respectively. Items 2 and 7 were scored in reverse order as they measured positive emotions. Total scores were calculated by summing the scores of the 11 items, and depression was defined as a total score of ≥ 8.8.

Satisfactions

Job satisfaction and satisfaction with other domains of life (health, residence, income, family relationships, social relationships, and leisure) were measured using single-item questions on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Very dissatisfied’ (1 point) to ‘Very satisfied’ (5 points). The categories ‘Very dissatisfied’ and ‘Dissatisfied’ were combined into ‘Dissatisfied,’ ‘Neutral’ remained as ‘Neutral,’ and ‘Satisfied’ and ‘Very satisfied’ were combined into ‘Satisfied.’

Covariates

Sociodemographic and health-related covariates included age, education level, marital status, chronic disease, smoking, and alcohol dependence. Age was categorized as 20–30s, 40–50s, and 60s. Education level was categorized into three groups: middle school, high school, and college or higher. Marital status was categorized into two groups: living with a spouse and being single due to reasons such as unmarried, divorced, separated, or widowed. Chronic diseases were classified based on receipt of medical treatment or medication for more than six months. Smoking status was divided into two groups: current smokers and ex-smokers/lifelong non-smokers. The presence of alcohol dependence was assessed using the AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test) score. The AUDIT scale, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), consists of 10 items and measures the frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption in the past year, alcohol dependence symptoms, and alcohol-related problems across three domains (harmful alcohol use, alcohol dependence, and hazardous alcohol use).19 The values of the 10 variables recoded were summed to calculate total scores. A score of zero indicated no alcohol consumption. The WHO interprets a total score of ≥ 8 as alcohol dependence and at risk of harmful drinking. In this study, scores below 8 were classified as ‘normal,’ and scores of ≥ 8 were classified as ‘alcohol dependent.’

Work-related factors included income, employment type, and working hours. Income was calculated as equivalized disposable income, which was calculated by dividing household disposable income by the square root of the number of household members. Incomes were then classified into quartiles: top 25%, 25%–50%, 50%–75%, and bottom 75%–100%. Employment type was categorized into three groups: permanent, temporary, and daily. Working hours were converted to weekly working hours and categorized into three groups: ≤ 40 hours/week, >40 hours but < 60 hours/week, and ≥ 60 hours/week.

Statistical analysis

Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the influence of job satisfaction on depression using odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Due to the sex-dependent prevalence of depression,20 participants were divided into male and female groups. The dependent variable was the presence of depression, and initially, a crude model was analyzed using only job satisfaction as the independent variable. In the second model, sociodemographic and health-related factors were included as covariates, and in the third model, work-related factors were included. In the final analysis, all previously included variables and satisfactions with 6 other domains of life were combined. The analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Inha University Hospital (IRB approval No. 2023-10-034).

RESULTS

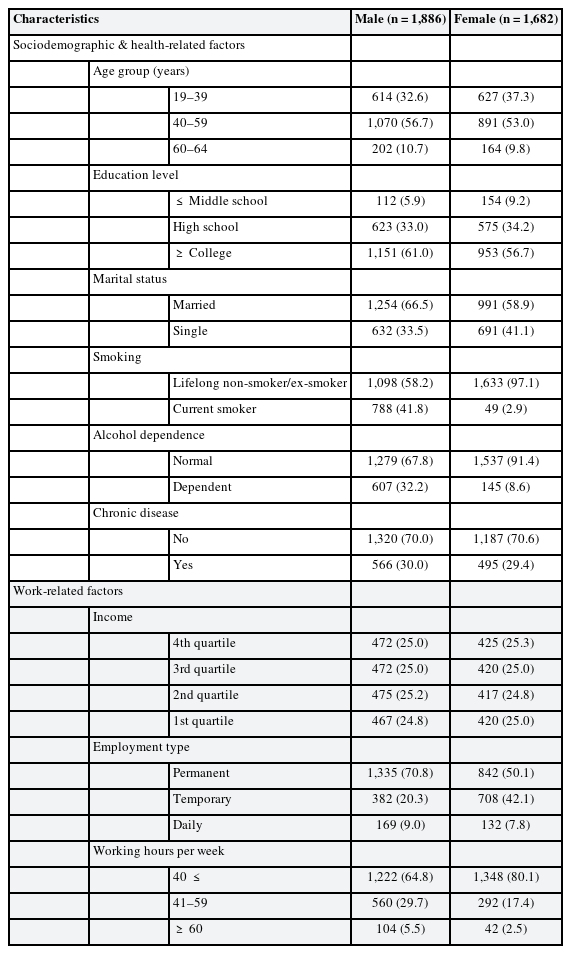

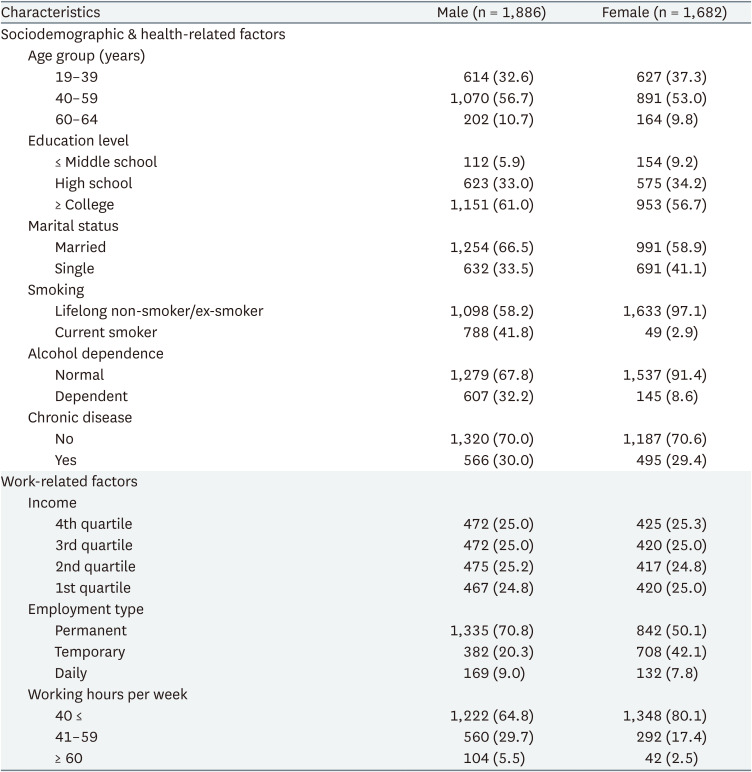

Among the 3568 study participants, there were 1886 men (52.9%) and 1682 women (47.1%). For men and women, over half were aged 40 to 59 (1,070 [56.7%] and 891 [53.0%], respectively). In terms of education, more than 90% of men and women had completed high school or higher education. The proportion of full-time workers was 70.8% for men and 50.1% for women, and the percentages of men and women working < 40 hours per week were 64.8% and 80.1%, respectively (Table 1). In males, 74 subjects (3.9%) had depression, while in females, 147 subjects (8.7%) had depression.

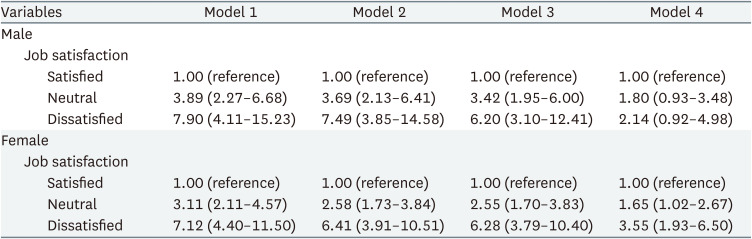

The main results of this study are summarized in Table 2. Both men and women showed a significant association between job satisfaction and depression, which remained consistent in model 2 after adjusting for sociodemographic and health-related factors and in model 3 after adjusting for work-related factors. For both men and women, lower job satisfaction was associated with an increased risk of depression. In model 4, which further adjusted for satisfaction with 6 other domains of life (health, residence, income, family relationships, social relationships, and leisure), a significant association between job satisfaction and depression remained for women, that is, lower job satisfaction was associated with a higher risk of depression. However, the association between job satisfaction and depression disappeared for men.

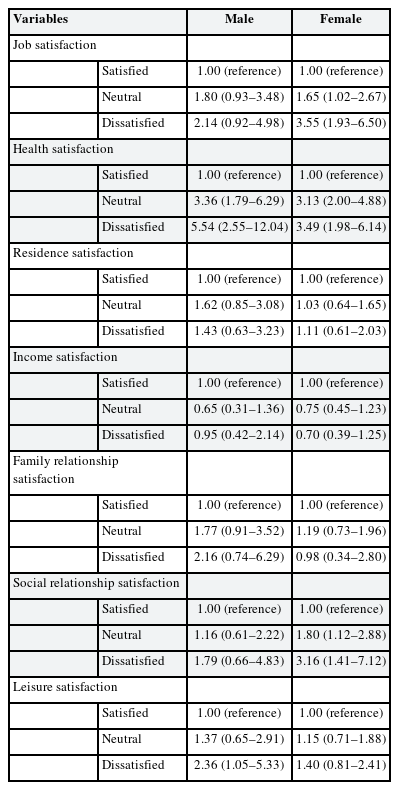

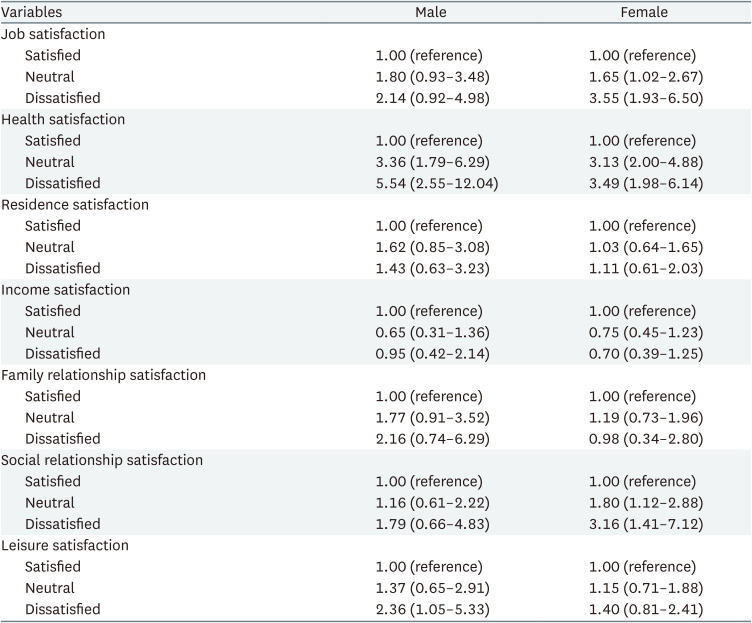

A significant association between health satisfaction and depression was observed for men and women. For men, leisure satisfaction was significantly associated with depression, while for women, satisfaction with social relationships was significantly associated with depression. However, for men, association between leisure satisfaction and depression was only significant in the dissatisfied group (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This analysis of the impact of job satisfaction on depression reveals that when satisfaction with other domains of life is not considered, job satisfaction is significantly associated with depression in men and women. However, after adjustment for satisfaction with other life domains, the significance of this association remains for women but not men.

We found that in women, as job satisfaction decreases, the risk of depression increases, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies on the relationship between job satisfaction and depression in women. A significant association between job satisfaction and depression was reported in a study conducted on female nurses.21 In addition, a study conducted on a group of nurses (94.8% were women) also revealed a negative correlation between job satisfaction and depression.22 Furthermore, another study conducted on nurses (99% were women) showed that cumulative job dissatisfaction was associated with depression.23

Unexpectedly, the association between job satisfaction and depression remained in female workers but was lost in male workers after including satisfaction with the 6 life domains. This difference may have been caused by sex-associated differences in sensitivity to job stress as it has been shown that female workers are more vulnerable to job stress than male workers.24 Job stress is positively associated with both job satisfaction and depression.25 Thus, female workers are probably at higher risk of depression than male workers even in same occupations. Furthermore, job satisfaction affects burnout, and burnout influences depression.26 Research results on sex differences in burnout are not consistent, but some studies that targeted specific occupations found that women are slightly more vulnerable to burnout than men.2728 Therefore, when job satisfaction is low, women may be more prone to experiencing burnout, and this could increase the risk of depression.29 Further studies are needed to analyze the mediatory effect of burnout and to determine the effect of adjusting for job stress.

The disappearance of the association between job satisfaction and depression in men after including satisfaction with the 6 life domains suggests the relative insignificance of the impact of job satisfaction on depression compared to other satisfactions. For men, the effects of health satisfaction and leisure satisfaction on depression were significant. In traditional patriarchal systems, men’s occupational activities have been considered an essential means of maintaining family livelihood. Paradoxically, men may consider occupational engagement as a duty regardless of job satisfaction, and this may place greater emphasis on satisfaction in other domains of life. In women, it was observed that social relationship satisfaction was inversely associated with the risk of depression. Interpersonal relationships within the workplace are an important aspect of social relationships, and satisfaction with coworker relationships is a critical component of job satisfaction. Therefore, women workers with low social relationship satisfaction may be dissatisfied with interpersonal relationships in the workplace, which would adversely influence job satisfaction and amplify the impact of job satisfaction on depression.

This study has the advantage of representing the general population rather than a specific occupational group. Many studies have reported relationships between job satisfaction and depression in specific occupational groups. In contrast, we used data from the Korean Welfare Panel Study, which includes diverse age groups, regions, educational backgrounds, and occupations. In addition, by conducting separate analyses on men and women, this study highlights potential differences between the sexes on the impact of job satisfaction on depression. Job satisfaction metrics are based on subjective evaluations based on worker job experiences, and the influence of job satisfaction on mental health may be greater than those of objective occupational factors (e.g., working hours, compensation, company size, or job position). For example, according to one study, workers who are satisfied with their jobs are less likely to experience depressive symptoms even when they work long hours.30

The present study has a number of limitations that warrant consideration. First, the study is inherently limited by its cross-sectional design, which means that although correlations can be identified, it is difficult to establish causality. Moreover, while job satisfaction may influence depression, there is also a possibility of reverse causality, which would increase the risk of overestimating the impact of job satisfaction. Additional prospective cohort studies are needed to determine the precise nature of the causal relationship between job satisfaction and depression. Second, an abridged version of the CES-D was used to determine the presence of depression rather than clinical diagnoses, which may have introduced information bias. However, the CES-D is a validated assessment tool for screening depression and has been widely used in previous studies. Third, the Korean Welfare Panel Study focuses primarily on low-income households, and approximately half of the sample belonged to these households, which introduces the possibility of selection bias. However, since incomes were well distributed and income was adjusted for during the analysis, we believe the extent of bias is unlikely to have affected our results. Fourth, using single-item measures for satisfaction limits the evaluation of subcomponents of satisfaction. For example, job satisfaction is the result of many factors such as salary satisfaction, creativity, autonomy, job characteristics, satisfaction with colleagues, and educational opportunities,31 and these sub-factors were not analyzed separately. Thus, it was not possible to determine the impacts of individual factors on the relationship between job satisfaction and depression. Fifth, though 6 additional life satisfactions in addition to job satisfaction were included in the analysis, other domains of satisfaction may be associated with depression. However, we believe that satisfactions examined in this study adequately reflect crucial aspects of life.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we found that job satisfaction is related to depression in Korean workers. Furthermore, when satisfaction with other life domains was considered, this association remained significant for women. Regular screening of job satisfaction should be considered a means of preventing and managing depression among female workers.

Notes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions:

Conceptualization: Yang S, Park SG.

Data curation: Park SG.

Formal analysis: Yang S, Park SG.

Methodology: Kim JH, Jung M, Park SG.

Supervision: Kim HC, Leem JH, Park SG.

Writing - original draft: Yang S.

Writing - review & editing: Kim JH, Jung M, Kim HC, Leem JH, Park SG.

Abbreviations

CI

confidence interval

IRB

Institutional Review Board

OR

odds ratio

WHO

World Health Organization