Association between exposure to violence, job stress and depressive symptoms among gig economy workers in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background

Gig workers, also known as platform workers, are independent workers who are not employed by any particular company. The number of gig economy workers has rapidly increased worldwide in the past decade. There is a dearth of occupational health studies among gig economy workers. We aimed to investigate the association between exposure to violence and job stress in gig economy workers and depressive symptoms.

Methods

A total of 955 individuals (521 gig workers and 434 general workers) participated in this study and variables were measured through self-report questionnaires. Depressive symptoms were evaluated by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 when the score was greater than or equal to 10 points. The odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was calculated using multivariable logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, working hours, education level, exposure to violence and job stress.

Results

19% of gig economy workers reported depressive symptoms, while only 11% of general workers reported the depressive symptoms. In association to depressive symptoms among gig economy workers, the mainly result of odds ratios for depressive symptoms were as follows: 1.81 for workers type, 3.53 for humiliating treatment, 2.65 for sexual harassment, 3.55 for less than three meals per day, 3.69 for feeling too tired to do housework after leaving work.

Conclusions

Gig economic workers are exposed to violence and job stress in the workplace more than general workers, and the proportion of workers reporting depressive symptoms is also high. These factors are associated to depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the gig workers associated between depressive symptoms and exposure to violence, job stress.

BACKGROUND

Gig workers, also known as platform workers, are independent workers who are not employed by a specific company. Over the past decade, the number of gig economy workers and digital labor platform workers has increased rapidly worldwide, thanks to advancements in new technologies and information.1 They can be characterized as on-demand, online platform-based, and temporary job workers. Along with the development of digital technologies, platform labor has emerged as a new employment type based on the platform’s network-type market intermediary function.2 According to a survey conducted by the Ministry of Employment and Labor of Korea in 2020, there were approximately 1.79 million platform workers in South Korea, accounting for 7.4% of the total employed population. Furthermore, it was found that over half (53.9%) of platform workers were employed as regular employees. Although the proportion of workers in the gig economy is increasing, research on occupational health is lacking because it is not a traditional employment type. In addition, they are not protected by the social system, such as workers’ compensation insurance, making them particularly vulnerable.

Several studies have examined the health consequences of workplace threats and violence. Exposure to work-related threats or violence has been found to be associated with an increased risk of depression two years later.3 A meta-analysis in which found a relative risk (RR) of depression, after exposure to work-related violence and threats.4 other study investigate association between violent episodes and prescriptions of antidepressants among nurses, police officers and security workers.5 Additionally, stress, particularly job-related stress, is a psychological issue and a widespread phenomenon that can lead to adverse health outcomes. Job stress influenced by both work characteristics and personal traits. Numerous studies have been conducted show a positive correlation between job-related stress and depressive symptoms.678 However, there is a limited research on gig workers, and only a few studies have investigated the relationship between replacement drivers and depression in Korea.910 Therefore, further research is necessary to explore gig workers response to negative customer treatment.

The common duty of platform labor in Korea includes drivers, such as replacement drivers and food delivery, as well as professional services, housekeeping, and production. Unlike other studies on gig workers, that addressed only replacement drivers, this study attempted to include several gig worker’s fields, including replacement drivers, food delivery drivers, and housekeeping. Gig economy workers exhibit heterogeneity in factors confounding depressive symptoms, including education level, and weekly working hours.111213 Therefore, there is a need for comprehensive research on gig economy labor, including factors such as depression, exposure to violence as there is a lack of studies examining the association of these factors with platform labor. While previous studies have examined the health of gig economy workers,141516 there has been a scarcity of research specifically focused on the Asian region. Furthermore, a new type of job stress related to work-life imbalance has not been extensively studied in gig economy workers.

In this study, our focus was on the health of gig economy workers, specifically investigating occupational exposure to violence related to depressive symptoms. Additionally, we aimed to explore the association between various job stressors and depressive symptoms.

METHODS

Data and study population

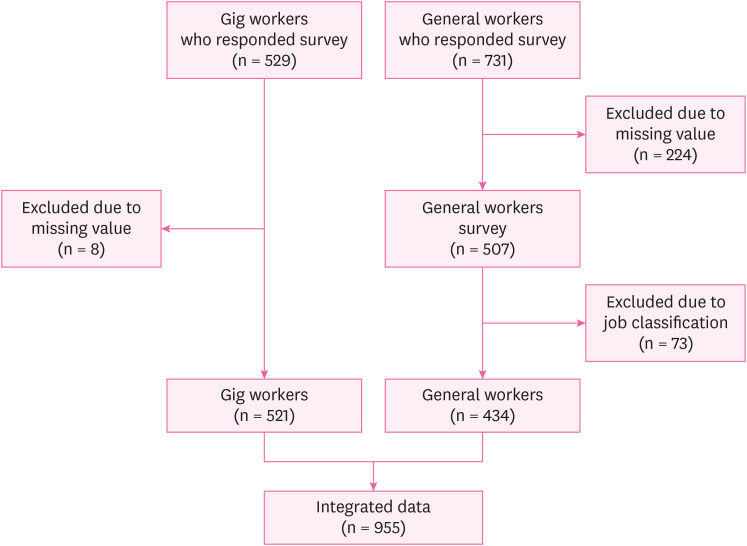

Our study used two self-reporting questionnaires. One questionnaire for gig workers, collected online and offline from November 2021 to August 2022. The researchers conducted offline surveys in person and also received surveys via email. Gig workers are working as replacement drivers, housekeepers, and food delivery drivers. From a total 529 participants responded to the survey, 521 participants remained in the analysis with excluding those who had missing value (n = 8). Another survey for general workers, online survey was conducted in February 2022, for those aged 19 or older. The survey was randomly selected through a professional research company, and e-mails were sent. Among them, 731 people responded, and data were collected from 507 people, excluding those who had missing values. From a total of 507 participants, 434 participants remained in the analysis after excluding who were not working as officer, service worker, manual worker (n = 73). Finally, this study included a total of 955 participants, consisting of 521 gig workers and 434 general workers, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The job classifications in the general workers were as follows: 307 officers (70.7%), 69 service workers (15.9%), and 58 manual workers (13.4%). Both questionnaires investigate the demographic questions about sex, age, working hours, educational level and occupational characteristics including violence and job stress exposure and psychological, chronic disease status. All questions on violence asked whether they had experienced it in the past 12 months. Questions related to exposure to violence included verbal violence, humiliating treatment, blasphemy experience, physical violence, and sexual harassment. The questions about exposure to job stress include: 'Forced to work beyond contract,’ ‘number of meals per day,’ ‘I have to suppress my own emotions at work,’ ‘I worry about work even when not working (lunch break, after work, weekend, vacation),’ ‘I lack time to spend with family due to work’ and ‘I am too tired to do housework after leaving from work.’ They were asked about their experience and number of episodes in the past 12 months. Other questions about job stress were surveyed with five responses: ‘not at all,’ ‘almost never,’ ‘sometimes,’ ‘mostly yes,’ and ‘always.’

Variables

In this study, the validated PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire) was utilized as a screening tool to assess depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 is a self-report questionnaire developed in 1999 and has been validated in the domestic setting.17 It is composed of a 4-point Likert scale, and each item is selected based on the frequency of symptoms. The scores for each item range from ‘not at all,’ which is the lowest score of 0 points, to ‘nearly every day,’ which is the highest score of 3 points. The criteria for determining depressive symptoms are as follows: a total score of less than 5 indicates ‘none,’ 5–9 points indicate ‘mild,’ 10–14 points indicate ‘moderate,’ 15–19 points indicate ‘moderately severe’ and 20 or more point indicate ‘severe.’ In this study, the presence of depressive symptoms was evaluated, and a total score of 10 or higher was considered indicative of having depressive symptoms and thus warranting consideration for treatment. Age, sex, working hours, and education level were adjusted as covariates. Age was classified as 35 or younger, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and 65 years or older. Working hours per week were classified as less than 40, 40–52, more than 52 hours. The total number of hours worked at the time was divided based on the working hours of the Korean Labor Standards Act. Education level was classified as below high school graduation, college graduation, university graduation, and above graduate school. The variable related to exposure to violence divided into two categories: whether subjects have experienced or not. The variables related to exposure to job stress divided into two categories as well: low frequency and high frequency. ‘Not at all’ and ‘almost never’ classified as ‘low frequency,’ ‘sometimes,’ ‘mostly yes’ and ‘always’ classified as ‘high frequently.’

Statistical analysis

After evaluating the baseline general characteristics of the study participants, a chi-square test was conducted to examine the demographic characteristics and exposure to violence and job stress based on the workers type and depressive symptom. We analyzed the association between worker type and depressive symptoms using univariate logistic regression and multivariate logistic regression analysis, which included workers type, age, sex, working hours and educational level, with all study participants. Moreover, we analyzed the association between exposure to violence, job stress and depressive symptoms among gig workers using multivariate logistic regression which adjusted for age, sex, working hours and educational level. Regression models were calculated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Analysis results with a p-value of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R version 4.1.2.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital (Approval number: 4-2021-1447).

RESULTS

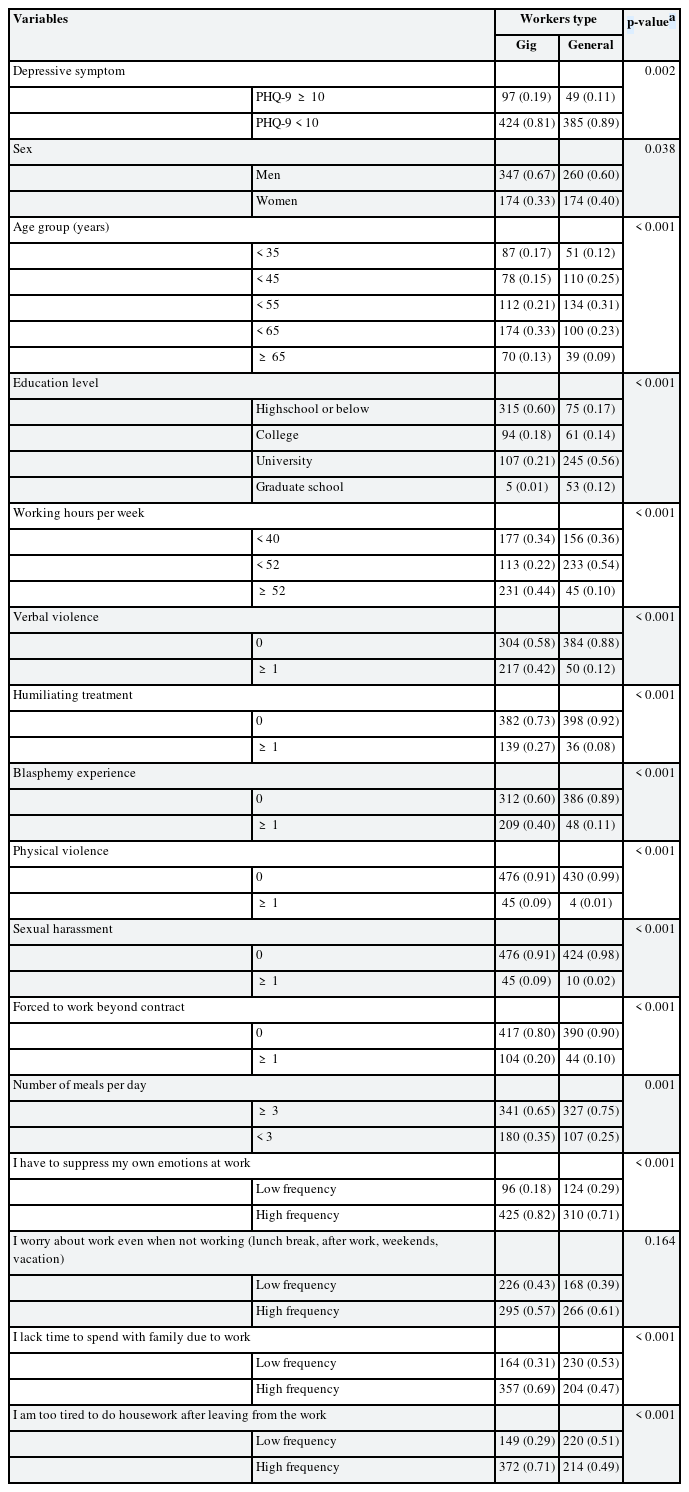

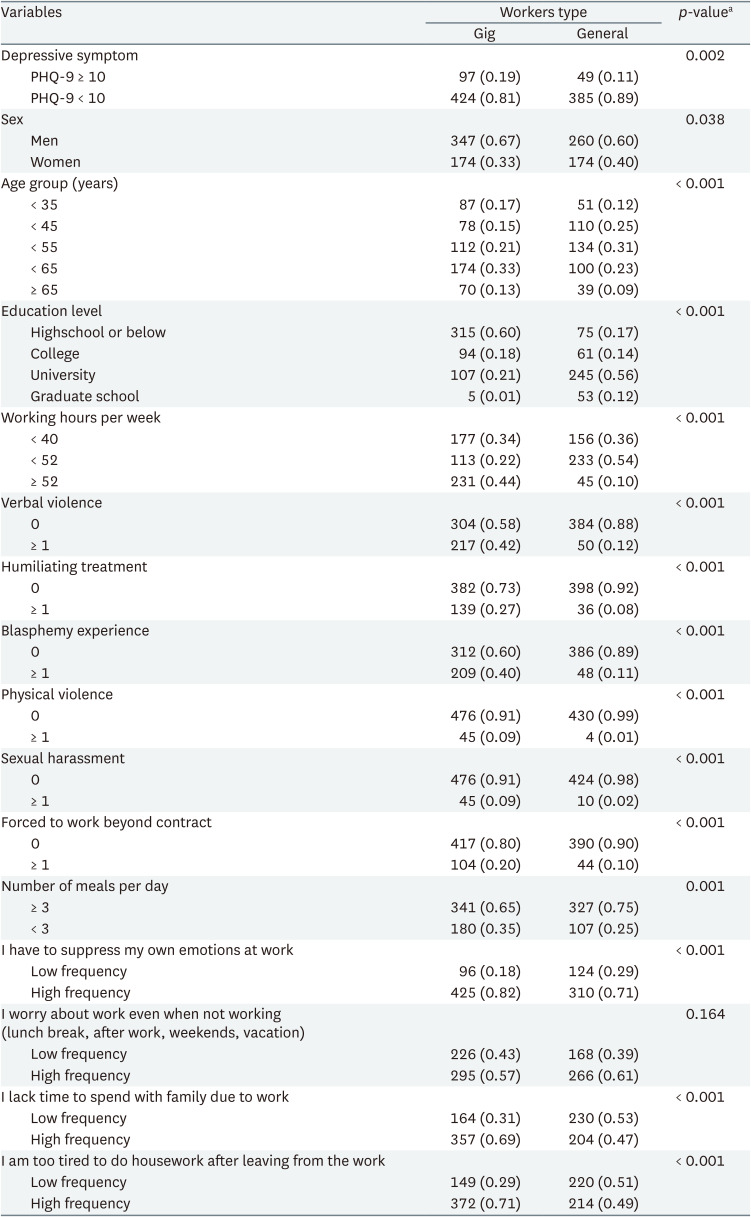

Among 955 people (521 gig workers, 434 general workers), 97 (19%) gig workers and 49 (11%) general workers reported symptoms of depression (Table 1). We observed a significantly higher proportion of gig workers exposed to violence for the following characteristics: verbal violence, humiliating treatment, blasphemy experience, physical violence and sexual harassment. Additionally, most of the job stress questions revealed the same results except ‘I worry about work even when not working.’ The proportions of gig workers exposed to job stress was higher than general workers for the follows: ‘forced to work beyond contract,’ ‘lacking number of meals per day,’ ‘I have to suppress own emotions at work,’ ‘I lack of time to spend with family due to work’ and ‘I am too tired to do housework after leaving from the work.’

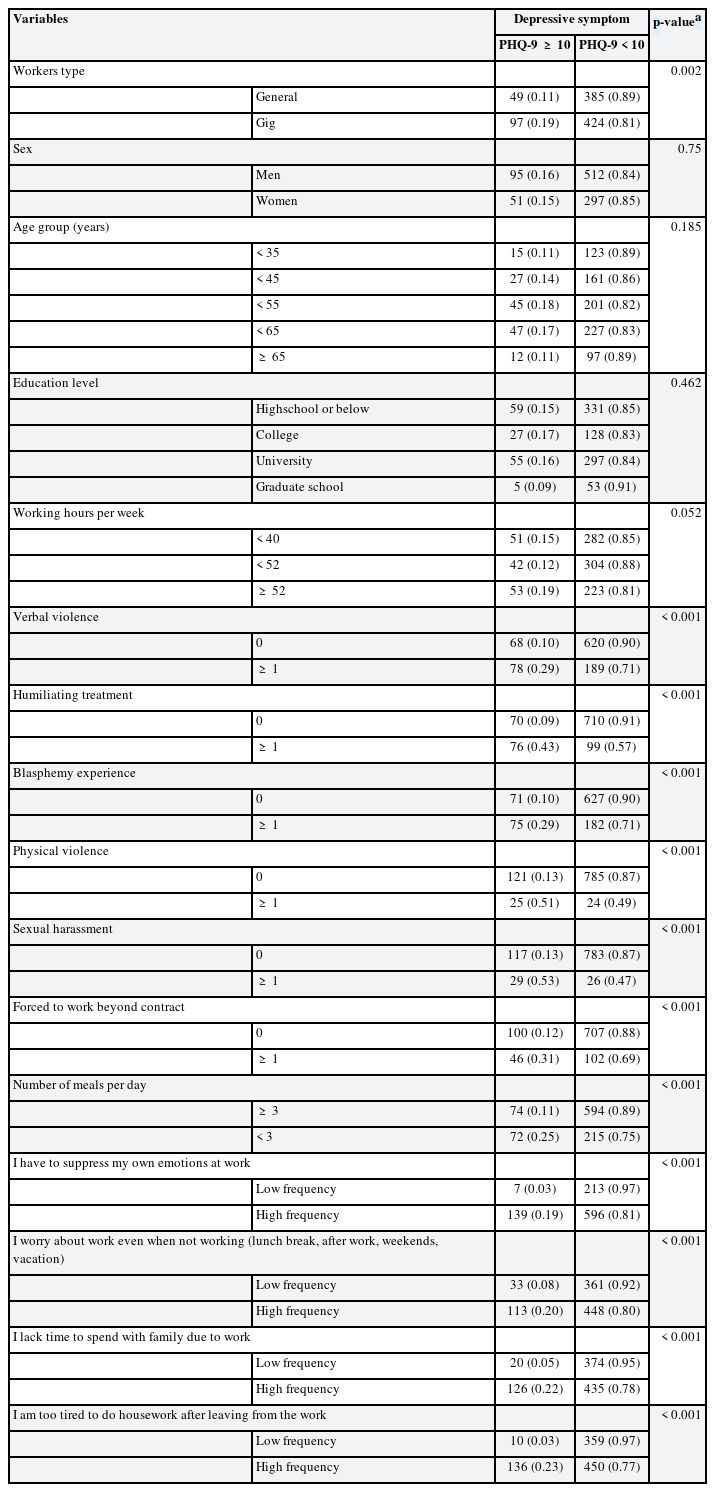

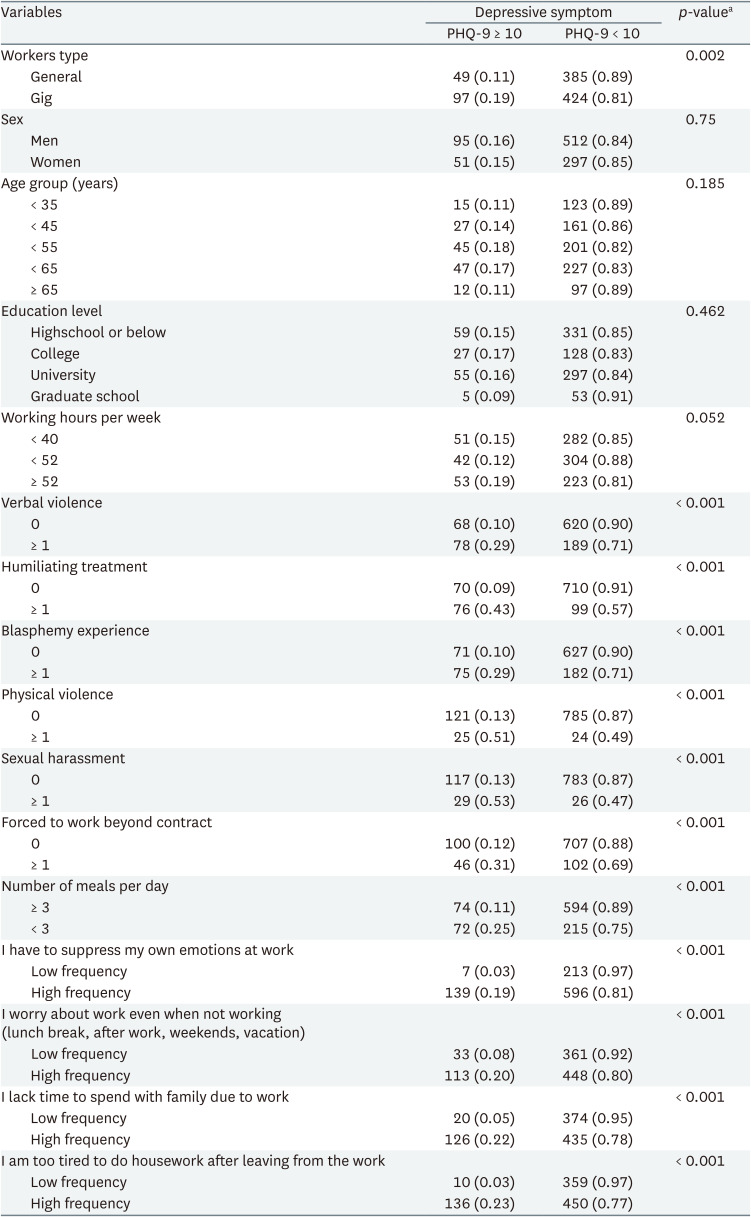

Table 2 shows that the prevalence of depressive symptoms is greater among gig workers and individuals working more than 52 hours per week. Furthermore, it is observed that individuals exposed to verbal violence, humiliating treatment, blasphemous experiences, physical violence, sexual harassment, as well as those experiencing emotional suppression and work-family conflicts, also exhibit a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms.

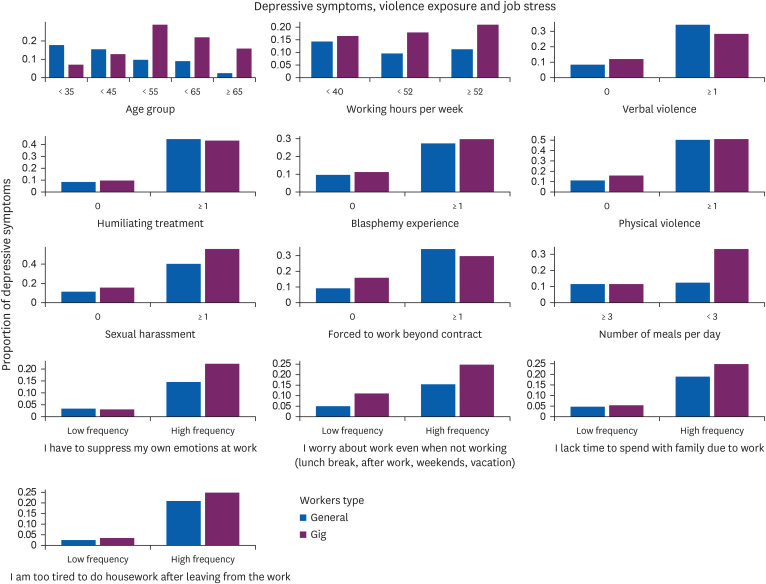

Fig. 2 presents the proportion of depressive symptoms according to variables. Gig workers had similar results to those of general workers about exposure to violence. However, a much higher proportion of gig workers showed symptoms of depression than general workers when they were 45 years of age or older or worked more than 40 hours per week. In most exposure to job stress gig workers showed a higher proportion compared to general workers, especially the number of meals per day was less than 3. On the contrary, when workers were forced to work beyond contract, general workers showed a higher incidence of depressive symptoms.

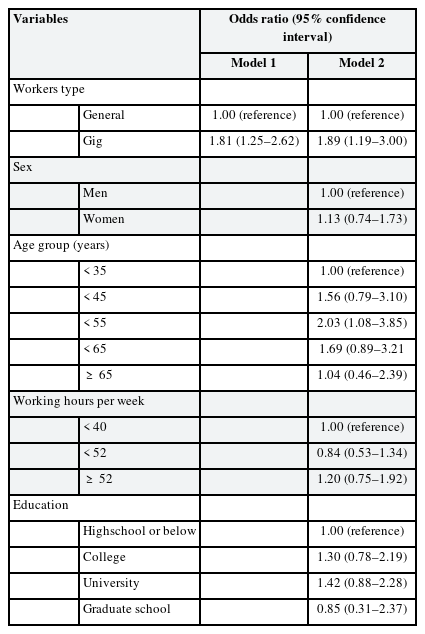

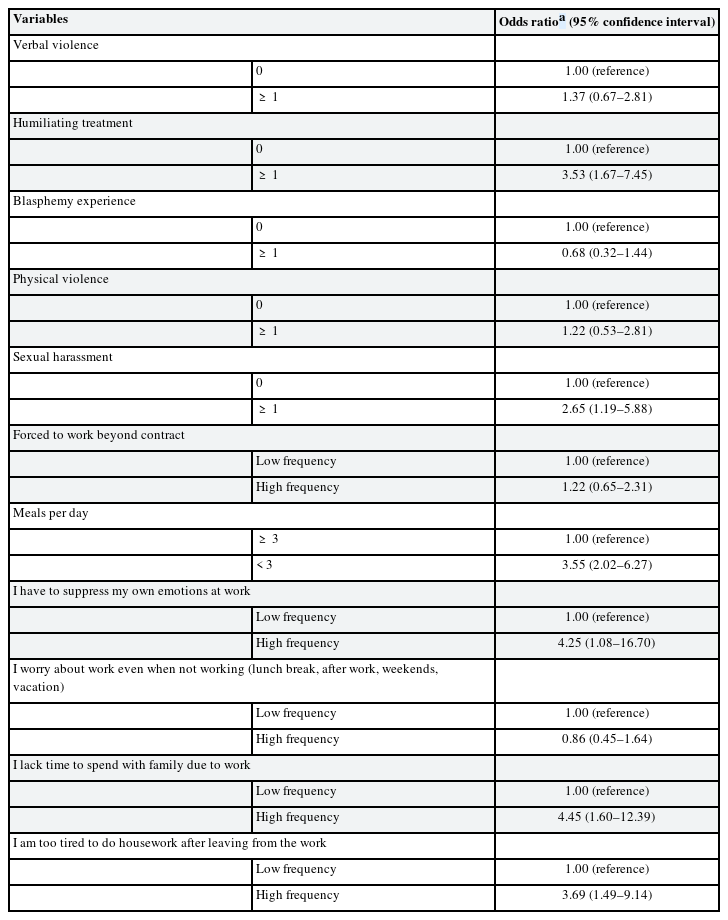

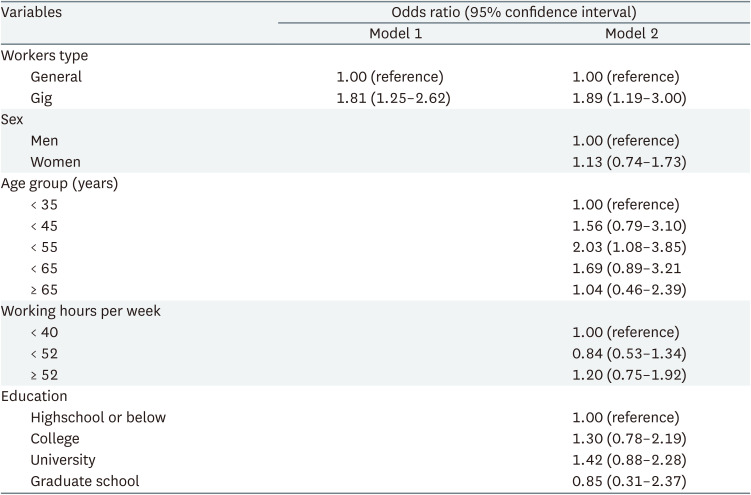

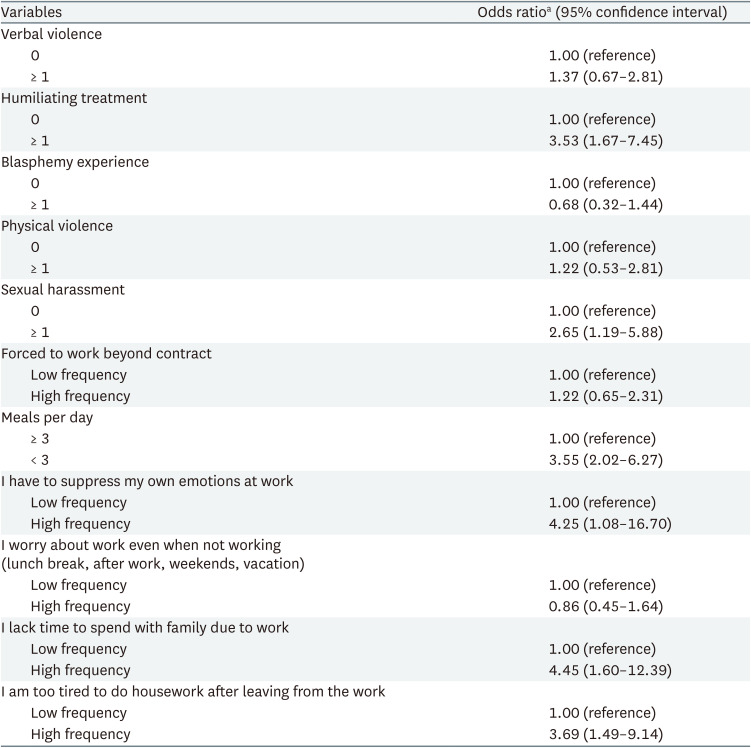

Table 3 presents multivariable logistic regression model of depressive symptoms. Model 1 show univariate logistic regression model and the OR (95% CI) of depressive symptoms were 1.81 (1.25–2.62) for gig workers. Model 2 adjusted general characteristics including sex, age, working hours per week and education. The OR (95% CI) of depressive symptoms were 1.89 (1.19–3.00) for gig workers. Table 4 presents the association between exposure to violence, job stress and depressive symptoms among gig workers using multivariate logistic regression which adjusted for age, sex, working hours and educational level. In exposure to violence, the OR (95% CI) of depressive symptoms were 3.53 (1.67–7.45) for humiliating treatment and 2.65 (1.19–5.88) for sexual harassment. In exposure to job stress, the OR (95% CI) of depressive symptoms were 3.55 (2.02–6.27) for less than three meals per day, 4.25 (1.08–16.70) for ‘I have to suppress my own emotions at work,’ 4.45 (1.60–12.39) for ‘I lack time to spend with family due to work’ and 3.69 (1.49–9.14) for ‘I am too tired to do housework after leaving from the work.’

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the association of exposure to violence and job stress to depressive symptoms using a self-reported questionnaire among gig workers and our findings suggest this association. People who work in the gig economy, are also at high risk of developing depression symptoms if they are exposed to violence and job stress such as general workers. Moreover, gig workers are exposed to a greater frequency of various forms of violence and experience a significantly higher level of job stress across nearly all categories compared to general workers.

Consistent with the results of previous studies, this study found that gig workers also had an association between exposure to violence, job stress and depressive symptoms. Self-reported exposure to work-related threats and violence was associated with a risk of depression two years later, OR 2.20.3 A meta-analyses found RR 1.42 after exposure to work-related violence and threats.4 Violence perpetrated by patients and visitors was associated prescriptions of antidepressants a RR of 1.65 in healthcare workers.5 According to a cohort study conducted in Sweden, OR for the association between exposure to violence and depressive symptoms increased by approximately two to three times.18 In another cohort study conducted in Denmark, it was reported that individuals with a higher likelihood of work-related violence had a 1.11 times higher risk of developing depression compared to employees with lower exposure possibilities.19 Furthermore, previous research has demonstrated based on the cognitive theories of rumination that customer treatment can have a negative impact on an individual’s mood.20 A longitudinal study in Germany revealed association between job stress and depressive symptoms.21

We focused on the difference in the proportion of depressive symptoms between gig economy and general workers. This result is also similar to previous studies. Gig workers are not exactly the same as piece-rate workers. However, they share the same characteristics, in that they earn as much money as they work. According to a study, workers who receive piece-rate pay currently or in previous periods have a significantly increased likelihood of self-reported health limitations compared to those receiving salary-based pay.16 According to some studies, US workers who reported receiving piece-rate pay were more likely to report lower overall health status and poorer psychological distress compared to workers receiving salary-based pay.2223 Furthermore, the gig economy encompasses both the characteristics of platform labor and pieced-rate workers. Generally, gig economy work exhibits traits such as non-standard employment, flexibility, and job instability.242526 The expected earnings per hour for platform workers is low, but they depend on income earned through long working hours and labor.27 Platform workers do not enjoy the freedom of independent work and high income like freelancers, and often experience unstable employment conditions.2829 Customer satisfaction is closely related to platform worker income and has an impact on reputation within the platform.30

Contrary to traditional employees, gig workers are responsible for their own career development and often face precarious employment relationships with various platforms.31 These characteristics of gig workers can be seen as affecting the results of job stress in this study. Thus, gig workers more frequently suffered from a lack of daily meals, suppression of emotions at work, worries about work even when not working, and too tired to do housework after leaving the work, compared to general workers. These results attributed to the work environment for gig workers is different from general worker are considered to show differences in job stress associated with depressive symptoms.

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design made it impossible to determine the causal relationship between exposure to violence, job stress and depressive symptoms. Reverse causation cannot be ruled out. Second, we used variables measured using self-report questionnaires. It means the reliability of data obtained through online self-information research is not guaranteed. Future studies could benefit from using objective measures of variables and a longitudinal design. Third, unmeasured confounders, including income level, sleep disturbance and other possible covariates, might have existed due to insufficient information. Finally, another limitation is that the variables used to investigate job stress in this study are not based on previously established survey questions. The questions we used in our study are derived from qualitative research that identified the job difficulties faced by platform workers. This has limitations in terms of operational definitions.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study showed the gig workers associated with depressive symptoms. And exposure to violence and job stress was associated with depressive symptoms. There is a need for a social system that focuses on these workers. Policy researchers and related ministries should further develop and improve 'health management' programs for gig workers, a new form of work.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Notes

Fundings: This study was supported under the framework of international cooperation program managed by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021K2A9A1A01102239) and funded by a grant from the Korea Health Promotion Institute R&D project funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HS21C2367).

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions:

Conceptualization: Kim MS, Yoon JH.

Formal analysis: Yun BY.

Methodology: Kim MS, Sim J.

Project administration: Yoon JH.

Software: Kim MS, Yun BY.

Supervision: Yoon JH.

Validation: Yoon JH.

Visualization: Kim MS, Oh J.

Writing - original draft: Kim MS.

Writing - review & editing: Oh J, Sim J.

Abbreviations

95% CI

95% confidence interval

OR

odds ratio

PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire

RR

relative risk