The impacts of working time flexibilization on occupational safety and health: an expert survey

Article information

Abstract

The policy proposal by the current Korean government that proposes flexible overtime rules is causing social controversy. This study has explored the 612 experts’ opinions on the occupational safety and health impacts of the policy using an online self-report survey. They expected short-term overwork (87.25%), overwork inequality (86.44%), irregular working hours (84.31%), chronic overwork (84.15%), long working hours (83.66%), and unpredictability of working hours (81.86%) as a result of the policy change. They also responded that the policy change would increase industrial accident deaths (87.25%), mental illnesses (87.09%), deaths due to overwork or cardiovascular diseases (83.84%), and accidents (83.33%). They disagreed that the government’s flexibilization policy, while agreeing that the necessity of policies on regulating night work (94.77%), guaranteeing wages to eliminate overtime (90.36%), establishing working time regulations for the bogus self-employed (82.84%), and applying the 52-hour workweek system to all workplaces (76.47%). These expert opinions are consistent with previous research on the health effects of working hours.

The Korean government is currently reforming the working hour system. The government’s workweek reform proposal includes expanding overtime management units (averaging working hours), strengthening the right to choose rest breaks, eliminating blind spots in the application of working hours regulation, introducing a working time account system, and expanding the flexible working hour system. These are representative strategies of “internal numerical flexibility” in the labor market, which respond to economic changes through voluntary adjustment of working hours.12 Flexible working hour arrangements can reflect the needs of not only employers but also workers, especially in terms of guaranteeing job and employment security, working time autonomy, and work-life balance.3 Thus, flexibility in working time often presupposes a reduction in working hours, often in the form of job-sharing and protection from layoffs in times of economic crisis, as well as recommendations by the International Labor Organization (ILO) to protect workers from long working hours.4 Likewise, the government identifies working time autonomy, the right to health and rest, and flexible work arrangements as key principles and goals of the reform.

However, in Korea’s long working hour regime, the reform might exacerbate the long working hours and its negative health impacts rather than fulfill the stated goals.45 Unlike previous reforms shortening working hours,56 the current government’s reform aims to extend working hours. Working hours are one of the main social determinants of health. Long working hours and overwork have negative health impacts on stroke, heart diseases, articular fibrillation, hypertension, diabetes, fatigue, alcoholism, depression, anxiety, sleep, and cognitive disorders, cancers, and even occupational safety and health, death, and suicide.789101112 Flexible working time arrangements such as shift work and flextime can also adversely impact on health. Night shift work, for example, is considered “probably carcinogenic to humans.”13141516 Shift work has been associated with accidents, diabetes, weight gain, coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, sleep disorders, sexual and reproductive health, and etc.17181920 Nonstandard work schedules and their unpredictability have been negatively linked to sleep disorders, stress, anxiety, obesity, stroke, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, chronic fatigue, cancers, and diabetes.2122

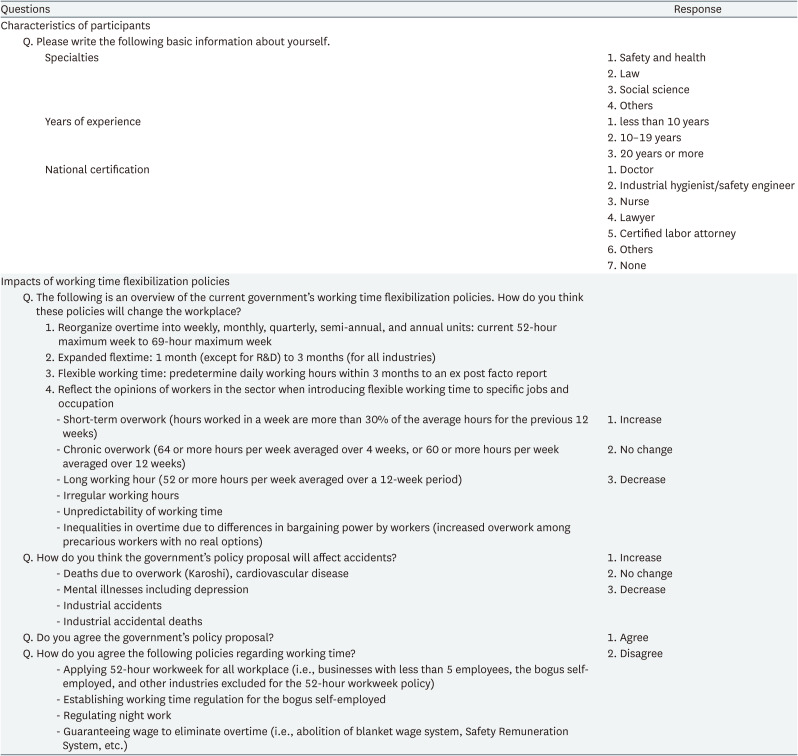

This study aimed to explore the opinions of experts on the occupational safety and health impacts of the Korean government’s policy initiatives to add flexibility to 52-hour workweek. The study used data from the one-year evaluation survey of the implementation of the Serious Accident Punishment Act. The survey was conducted online over 13 days between January 30 and February 11, 2023, targeting experts, on-site managers, and activities on occupational safety and health. The survey conducted convenience sampling through social network services and emails to 22 safety and health- or serious accident-related civil and academic societies. Six hundred twelve experts and activists agreed and participated in the survey. In this study, we analyze the responses to 3 questions about the characteristics of participants and fifteen questions about government’s policy proposal for the flexible working time arrangement (Table 1).

Expert opinion survey questions on the impact of working time flexibilization policies on occupational safety and health

Of the 612 respondents, 60.95% were experts in safety and health, 17.48% were in law, and 12.25% were in social science. 26.96% of respondents were certified as industrial hygienists or safety engineers, 22.22% were doctors, 9.15% were nurses, and 8.66% were certified labor attorneys. A 21.73% did not have a professional license. Those with less than 10 years of experience and with more than 20 years of experience accounted for 36.27% each, followed by 27.5% with 10-19 years of experience.

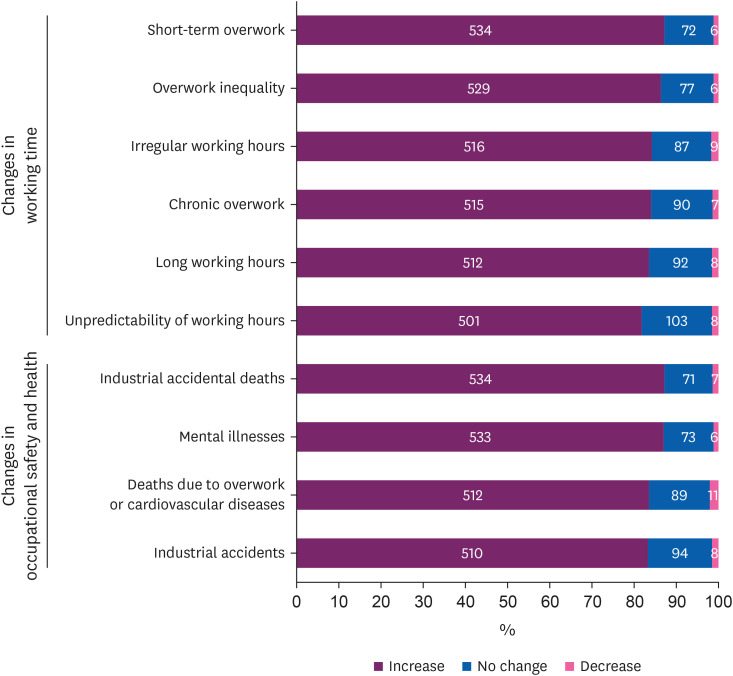

Fig. 1 shows respondents’ opinions on the expected changes in working hours and occupational safety and health in workplaces if the policies proposed were implemented. For the changes in working hours, respondents agreed that the policy would increase short-term overwork (i.e., hours worked in a week are more than 30% of the average hours for the precious 12 weeks) (87.25%), inequalities in overwork due to differences in bargaining power among workers (86.44%), irregularity of working hours (84.31%), chronic overwork (i.e., 64 or more hours per week averaged over 4 weeks, or 60 or more hours per week averaged over 12 weeks) (84.15%), long working hours (83.66%), and unpredictability of working time (81.86%). For the changes in occupational safety and health, they agreed that the policy would cause industrial accidental deaths (87.25%), mental illnesses such as depression (87.09%), deaths due to overwork (Karoshi), or cardiovascular diseases (83.84%), and accidents (83.33%).

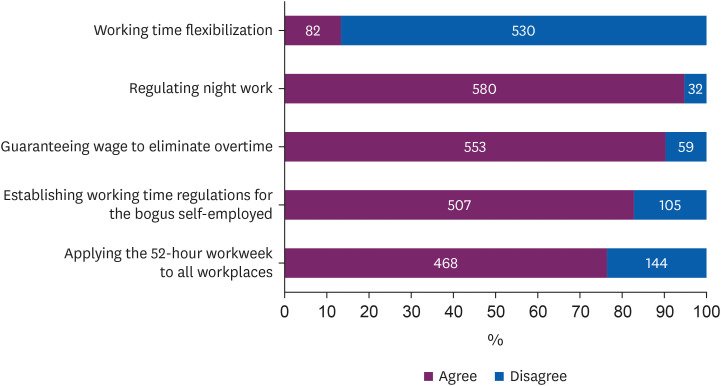

As Fig. 2 shows, 86.60% of respondents disagreed with the current government’s policy direction on flexibilization. On the one hand, they agreed that the necessity of following labor market policies: regulating night work (94.77%), guaranteeing wage to eliminate overtime (90.36%), establishing working time regulations for the bogus self-employed (82.84%), and applying the 52-hour workweek policy to all workplaces (e.g., businesses with less than 5 employees, the bogus self-employed, etc.) (76.47%). One respondent disagreed with the application of the 52-hour workweek policy, stating that a 40-hour workweek is more appropriate than a 52-hour workweek.

Consequently, experts have concerned that the current government’s policies proposal to reform working time flexibility could lead to poor working conditions including overwork, irregular and uncertain working hours, and long working hours, which in turn could cause negative health impacts, such as accidents, deaths, and mental illnesses. These expert opinions are in line with the findings of previous research on the negative impacts of working time flexibility on working conditions and health. Experts are also opposed to the policies proposal but called for more security-oriented policies regulating and shortening working hours.

Experts agreed that ensuring workers’ right to health requires directly regulating multi-dimensions of working time that negatively affect health.2324 The highest levels of agreement are found for regulating night work and guaranteeing wages to eliminate long working hours. The adverse health effects of night shift work are relatively well-known,1011 and low wage structures are often discussed as a cause of long working hours in South Korea.5 The government also agrees that the policy they proposed can lead to health problems as well. Thus, the proposal contains measures to secure workers’ right to health (i.e., 11 consecutive hours of rest, a limit of 64 hours per week, an average of 64 hours per four-week period and strengthen health protection for night work). However, considering how long working time causes health problems, it seems that these means are unlikely to protect workers’ health and/or mitigate the negative effects of long working hours and night-shift work. Moreover, given that increased working time flexibility, such as working time autonomy and flextime, encourages workers to exploit themselves by working longer and harder,25 and that this, in turn, leads to poor health, a more cautious approach to reforming working time regimes should be considered.

Experts also believe that negative effects of working time flexibilization are concentrated mostly on more vulnerable workers, exacerbating inequalities in accidents. High proportions of experts thus agreed on the need to protect precarious workers, including the bogus self-employed such as delivery workers, commercial truck drivers, freelancers, and workers in small businesses, who are excluded from working time regulations. Precarious workers fall outside the legal boundaries of the 40-hour workweek (with an extension to 52 hours) and are most likely to experience long working hours and occupational health problems.26 Similarly, the government claims that the policies proposals are a way to address the dual structure of labor market and protect outsiders. Nevertheless, given South Korea’s long working hour regime, labor market dualization, high wage flexibility, and low wage structure, as well as the male breadwinner model, working time flexibility further reinforces social and health inequalities.2527 In addition, in the absence of working time regulation for precarious workers, the choice of working hours through consensus between employers and employees with unequal power relations seems impossible.

On the one hand, the survey targeted experts only. Therefore, the study did not consider opinions of workers and citizens. According to a previous study, workers and citizens seem to disagree with the government’s policies proposals.28 For instance, an analysis of the National Work-Life Balance Survey 28 shows that the study participants want to work 36.7 hours per week. Those who work more than 52 hours per week want to work 44.2 hours. The government’s proposal mainly reflects and considers the recommendations from the Future Working Hours Study Group, represented by a few experts, in the decision-making process. Furthermore, the policy proposal is more employer-oriented.29 Further study on the political process of the current working time flexibilization policy is needed as working time is an area of politics in which the state, the economy, and workers with different interests interact.6 The participation of citizens and workers in the decision-making and reflection of their voices and needs are essential conditions for healthy public policy. Finally, we missed the importance of naming the system. As one respondent stated that a 40-hour workweek was appropriate rather than a 52-hour workweek, it is important to note that all references to a “52-hour workweek” in this study mean a “52-hour workweek ceiling.”

In 2022, the ILO’s General Conference added “a safe and healthy working environment” as a fundamental principle and right at work with the existing 4 rights: freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labor, the effective abolition of child labor, and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation. Working time is one of the most basic working conditions for decent work. In this context, working time has been a priority for international standards and regulations. It is recommended that working hours be reorganized and arranged through labor and management negotiation, especially when working hours adversely impact on workers’ health. The Serious Accident Punishment Act in South Korea also requires employers or managers to take measures to prevent harm or danger to the safety and health of workers. If the government’s policy reform threatens the lives of workers, it is necessary to rethink and readjust in a way to protect their safety and health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is the part of the evaluation of the Serious Accident Punishment Act conducted by the Serious Accidents Scholars and Experts Network. We would like to thank the Network members for their support and the members of 22 safety and health- or serious accident-related civil and academic societies who participated in the survey.

Notes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Moon D, Kim H.

Data curation: Moon D, Kim H.

Formal analysis: Kim H.

Investigation: Moon D.

Methodology: Moon D, Kim H.

Software: Moon D.

Validation: Kim H.

Visualization: Moon D.

Writing - original draft: Moon D.

Writing - review & editing: Moon D, Kim H.

References

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Data 1

Korean version paper