Association between long working hours and liver enzymes: evidence from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2017

Article information

Abstract

Background

Long working hours causes several health risks, but little is known about its effects on the liver. This study aimed to examine the correlation between working hours and abnormal liver enzyme levels.

Methods

We used data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey IV–VII. For the final 15,316 study participant, the information on working hours was obtained through questionnaires, and liver enzyme levels, consisting of serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), through blood tests. The relationship between weekly working hours and abnormal levels of liver enzymes was analyzed using multiple logistic regression, and a trend test was also conducted.

Results

In male, working ≥ 61 hours per week was significantly associated with elevated AST and ALT levels compared with working 35–52 hours per week. Even after adjusting for covariates, the odds ratios (ORs) of abnormal AST and ALT increased by 1.51 (95% confidence interval: 1.20–2.05) and 1.25 (1.03–1.52), respectively, and a dose-response relationship was observed. This association was more prominent among the high-risk group, such as those aged > 40 years, obese individuals, worker on non-standard work schedule, pink-collar workers, or temporary worker. No correlation was observed in female.

Conclusions

Long working hours are associated with abnormal liver function test results in male. Strict adherence to statutory working hours is necessary to protect workers’ liver health.

BACKGROUND

In 2020, Koreans had a total of 1,908 annual working hours and ranks 4th among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries with long working hours, meaning that they work 221 hours more than the OECD average of 1,687 hours.1 Long working hours have been recognized as a major social problem since the 1970s. In several epidemiological studies, long working hours increase the risk of chronic diseases2 such as metabolic syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular diseases.3 It can also adversely affect the mental health24 and cause psychological stress and work stress.5 In addition, it can promote poor lifestyle habits67 such as alcohol abuse, smoking, and physical inactivity, and can cause obesity.8 Although psychosocial job stress or changes in health behavior due to long working hours are likely have an negative effect on the liver,910 little is known about its effect on the liver.

The liver, which is called the factory of our body, controls various metabolic processes, and plays an essential role in maintaining homeostasis and health. An initial indicator of liver damage is aminotransferase, which consists of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and is collectively referred to as a liver function test (LFT). They may be elevated due to chronic hepatitis, alcohol or drug overdose, NAFLD, liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and abnormal immune reactions.11 In addition, there were studies that elevation of LFT is associated with various metabolic disease,12 and increase the mortality rate due to liver disease beyond the occurrence of various liver disase.1314 Liver disease is a burden not only in Korea but also in various countries, and its pattern is constantly changing.15 In the past, viral hepatitis and alcoholic hepatitis were the primary causes of chronic liver disease; however, the incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has been increasing.16 Recent studies have reported that long working hours are associated with the risk of NAFLD, thus it is thought that they may have a harmful effect on the liver, but there are few studies on this.1718

A recent study suggested a correlation between weekly working hours and liver damage, but it is difficult to generalize because this study only targeted a specific patient group.1920 Therefore, this study aimed to examine the relationship between weekly working hours and abnormal LFT using the data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), which is a representative sample survey conducted in the Korean population. Considering that the liver is an organ that represents sexual dimorphism21 and the health effects of long working hours may differ by sex, all analyses were conducted separately by sex.

METHODS

Participants

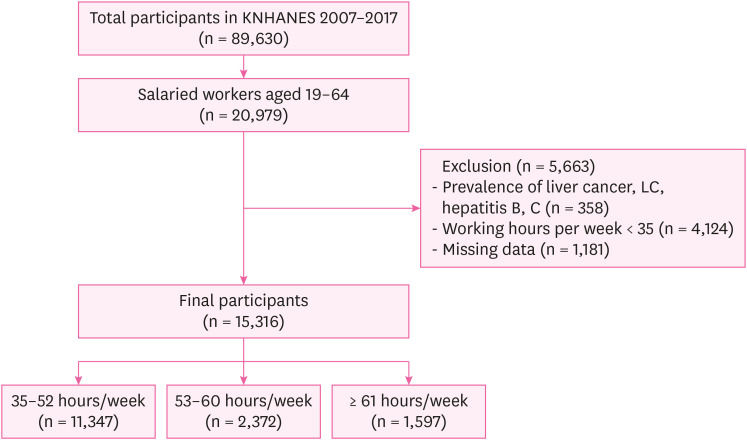

This study was conducted based on the data from the KNHANES 2007–2017. The KNHANES is a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey conducted periodically by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency and is designed using a 2-stage stratified cluster sampling. During the survey, the participants’ demographic data, socioeconomic status, health problems, health examinations, and nutrient intake are obtained. Of the 89,630 individuals who participated in the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th KNHANES (2007–2017), 20,979 salaried workers aged 19–64 years were the target study population. Individuals with liver cancer, liver cirrhosis, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C were excluded from the analysis. Individuals who worked less than 35 hours per week were also excluded as they were considered to have a greater socioeconomic impact than working hours. In addition, individuals with missing data on major variables and covariates were excluded. Finally, 5,663 participants were excluded, and a total of 15,316 participants were selected for analysis (Fig. 1).

Assessment of working hours

In KNHANES, the weekly working hours were measured using the following questions: “What is the average number of working hours per week (including overtime/overtime work) at your workplace? (excluding meal time).” According to the Korean Labor Standards Act, the maximum number of working hours per week is 52, including overtime.22 According to the Korean Enforcement Decree of the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act and Public Notice of the Korean Ministry of Employment and Labour, the compensation for chronic overwork-related cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases are approved in workers who worked over 60 hours in the past 12 weeks.23 The above hours are 30% and 50% added hours, respectively, through social agreement based on the 40-hour workweek, the statutory weekly working hour under the Korean Labor Standards Act. Therefore, we classified the working hour group as follows: 35–52 hours/week, 53–60 hours/week, and ≥ 61 hours/week.

Definition of abnormal liver enzymes

In KNHANES, blood sampling was performed in the mobile examination centers by a trained nurse or medical laboratory technician, who completed 2–4 weeks of training and received retraining sessions every year to reinforce the proper protocols and techniques. Serum AST and ALT levels were measured with a Hitachi Automatic Analyzer 7600-2100 (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) using the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine UltraViolet without pyridoxal-5-phospate method. According to the administrative criteria for health examination, the abnormal serum AST level (abnormal AST) is > 40 units per liter, while the abnormal serum ALT level (abnormal ALT) is > 35 units per liter.24

Other variables

Data on demographic characteristics such as sex and age, health behaviors such as smoking and drinking alcohol, and work-related factors were obtained using a standardized questionnaire. Age was divided into 4 groups: 19–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, and 50–64 years. Household income was divided into 4 quartiles: low, low-middle, middle-high, and high. Drinking status was classified into normal and heavy drinking, which was defined as drinking more than twice a week and drinking at an average of 7 or more units of alcohol for male and 5 or more units of alcohol for female.25 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing body weight by height in meter squared (kg/m2). BMI was classified into 2 groups: < 25 kg/m2 and ≥ 25 kg/m2. Metabolic syndrome was diagnosed when 3 of the following 5 criteria of the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III were satisfied: abdominal obesity (waist circumference: ≥ 90 cm in male and ≥ 85 cm in female), elevated blood pressure (systolic blood pressure of ≥ 130 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 85 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive drugs), elevated fasting blood sugar (≥ 100 mg/dL or use of glycemic control drugs), reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level (< 40 mg/dL in male and < 50 mg/dL in female, or use of drugs to treat low HDL), elevated triglyceride levels (> 150 mg/dL or use of medications to treat hypertriglyceridemia). Diabetes mellitus (DM) were defined as those with a fasting blood glucose of 126 or higher, who responded that they were taking diabetes medications or insulin injections, or had been diagnosed with diabetes.

In KNHANES, occupation was classified into ten categories according to the Korean Standard Classification of Occupations, which is based on the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08) adopted by the International Labor Organization. After excluding armed forces, we divided the remaining workers into 3 occupational categories (white-collar, pink-collar, and blue-collar) according to their job characteristics. The white-collar group consisted of managers, professionals and related workers, and clerks. The pink-collar group consisted of service and sales workers. Finally, the blue-collar group consisted of skilled agricultural; forestry and fishery workers; craft and related trade workers; equipment, machine operation, and assembly workers; and elementary workers. Employment status was categorized as follows based on the participants’ position at the workplace: permanent and temporary. Regular workers were categorized as permanent workers, while temporary employees or daily workers were defined as temporary workers. Type of work schedule was defined by the following question: “Do you usually work during the day (between 6 am and 6 pm)? Or do you work at a different time?” Those who answered “Mainly work during the day” were classified as on standard work schedule, while all others were classified as on non-standard work schedule.

Statistical analysis

After stratifying the data into male and female, the general characteristics of the study participants were described. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SDs), while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages (%). A χ2 test was performed to examine the ratio between abnormal AST and ALT levels according to working hours. Age, household income, obesity, metabolic syndrome, DM, job category, type of work schedule, and employment status were considered potential confounders. In general, education and job category are significantly connected, the effect of smoking on the liver is unknown, and liver cancer patients were excluded from the study, thus these variables were not considered as confounders. Drinking status was considered a mediator and excluded from covariates.

Multiple logistic regression was performed to evaluate the relationship between working hours and abnormal LFT and the integrated survey weight was used to consider the complex sampling design. To reduce the confounding bias, Model 1 was adjusted for age, household income, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and DM while Model II was further adjusted job category, type of work schedule, and employment status. The analysis presented the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). In addition, a trend test was conducted to examine the increase in the OR of abnormal LFT according to the increase in working hours. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a p value of < 0.05.

Ethics statement

The present study protocol was exempted from review by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, the Catholic University of Korea (approval No. KC21ZASI0536). Informed consent was obtained from all participants enrolled in the study.

RESULTS

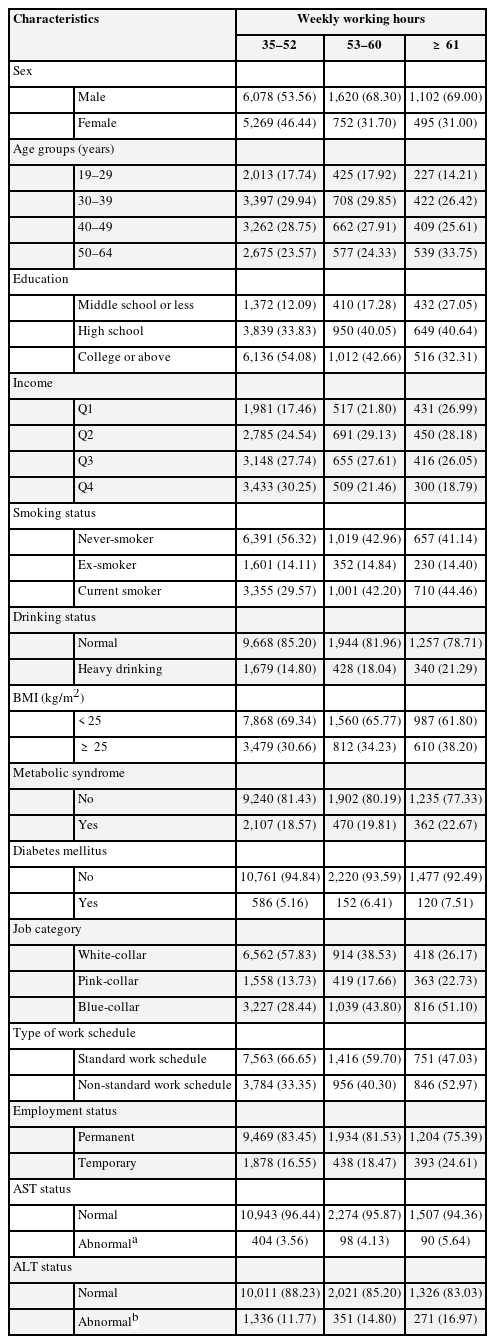

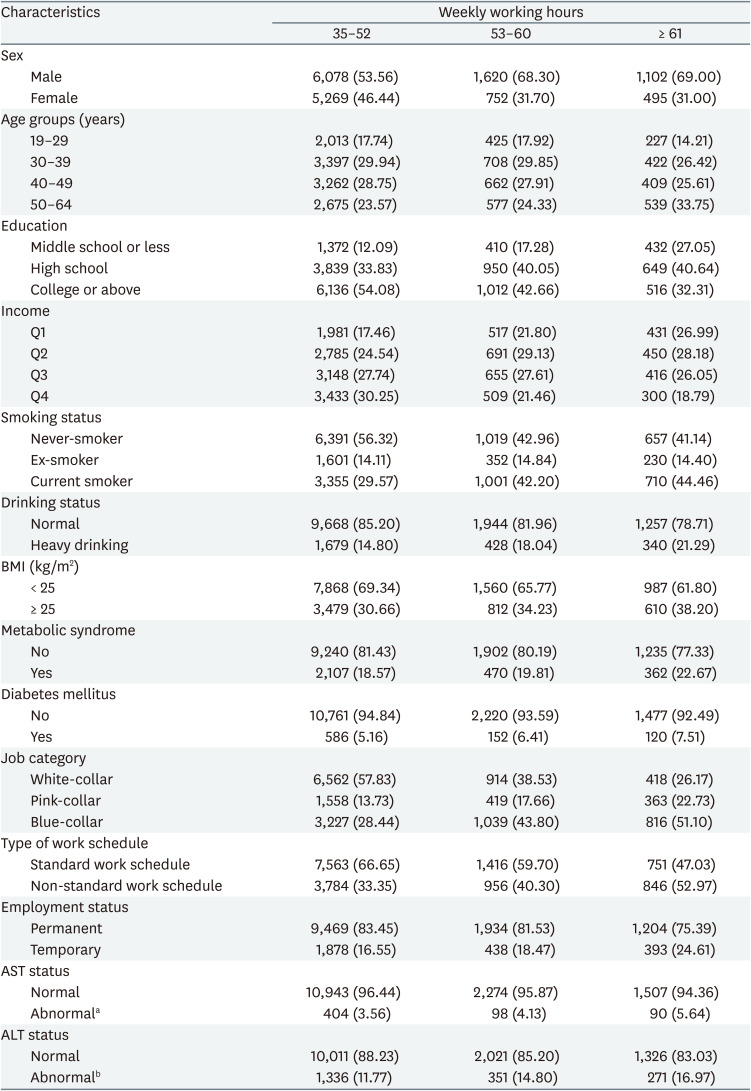

The general characteristics of the participants are listed in Table 1. Of the total 15,316 participants, 8,800 (57.46%) were male and 6,516 (42.54%) were female. The proportion of working more than 60 hours per week was higher in male than in female. The average AST and ALT levels of male were 24.09 IU/L and 27.59 IU/L, respectively, which were higher than those of female, 18.92 IU/L and 16.03 IU/L. The abnormal AST and ALT levels were 5.69% and 19.51% in male, respectively, and 1.40% and 3.70% in female.

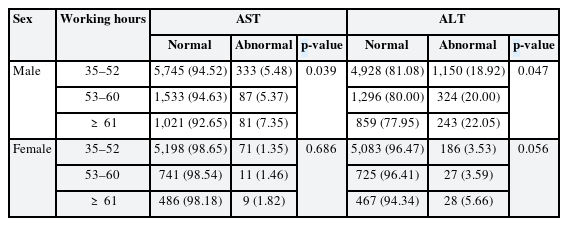

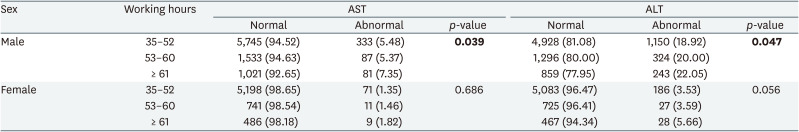

Table 2 shows the results of the analysis of the ratio of abnormal LFT levels according to working hours in male and female. In male, the ratio of abnormal AST levels was statistically significant different depending on working hours (p < 0.05), and it was observed that the ratio increased as the working hours increased. The ratio of abnormal ALT levels also was different with statistical significance (p < 0.05), and it seems to be increasing. No difference was observed in the ratio of abnormal LFT according to working hours in female.

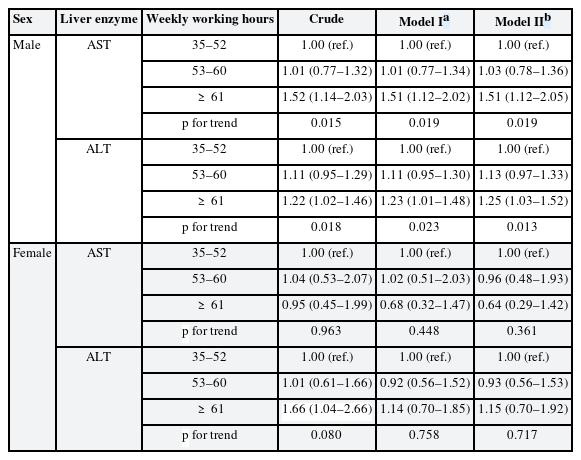

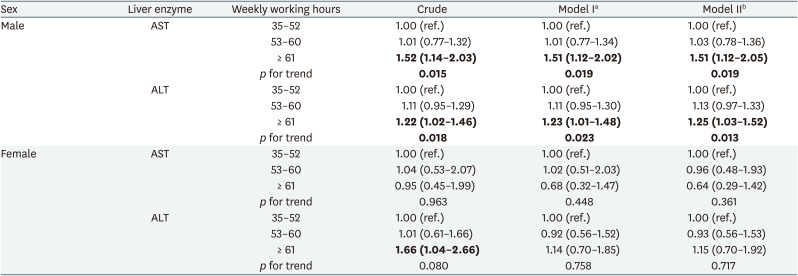

Table 3 shows the association between weekly working hours and abnormal LFT by multiple logistic regression; and the calculated crude and adjusted ORs and their 95% CIs. For male, the ORs of abnormal AST and abnormal ALT levels in those working ≥ 61 hours were 1.52 (95% CI: 1.14–2.03) and 1.22 (95% CI: 1.02–1.46) compared with those of the 35–52 weekly working hour group, respectively. After adjusting for age, income, obesity, metabolic syndrome, DM, the ORs of abnormal AST and ALT were significantly high at 1.51 (95% CI: 1.12–2.02) and 1.23 (95% CI: 1.01–1.48), respectively. Similar results were obtained with ORs of 1.51 (95% CI: 1.20–2.05) and 1.25 (95% CI: 1.03–1.52), even after further adjusting for income, job category, employment status, and shift work. Moreover, a statistically significant dose-response relationship was found consistently between weekly working hours and abnormal LFT, with or without adjustment (p for trend < 0.05). Meanwhile, no significant relationship was observed in female.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to examine the correlation between weekly working hours and abnormal LFT in a Korean population. The results of the current study showed that long working hours were associated with abnormal LFT even after adjusting for age, income, obesity, metabolic syndrome, DM, job category, type of work schedule, and employment status in male, with a dose-response relationship. As a result of sensitivity analysis by dividing weekly working hours into 4 groups (35–40/41–52/53–60/≥ 61), the ORs of abnormal AST and ALT were also significantly increased in the ≥ 61 hours group compared to 35–40 hours of work (Supplementary Table 1). The dose-response relationship between weekly working hours and abnormal LFT was maintained in ALT (p for trend < 0.05). However, no such relationship was observed in female.

The number of literatures on the relationship between working hours and liver function is limited. In a cross-sectional study of 6,086 Japanese workers conducted by Ochiai et al.,20 no correlation was observed between weekly working hours and abnormal LFT. However, since this study was conducted only in Japanese tertiary industry workers, there are limitations to the generalization of the results. A cross-sectional study using the Kangbuk Samsung Health Study showed that HBsAg(+) (hepatitis B surface antigen) participants who worked more than 60 hours per week had significantly higher OR of abnormal ALT, but no correlation was observed in all study participants.19 In addition, the above study has limitations in generalization because it was conducted only in white-collar workers with high educational levels. By contrast, the current study showed a consistent increase in male.

There are several plausible mechanisms by which working hours can lead to abnormal LFT. First, recent studies have reported that long working hours increase the risk of NAFLD,1718 a known hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome.26 In general, when workers work overtime, they feel physically tired, and their interest in physical activity decreases, which can limit leisure-time physical activity (LTPA).2728 Decreased LTPA may increase insulin resistance,29 which is one of the mechanisms of NAFLD development. Moreover, long working hours are associated with poor dietary behaviors, such as skipping breakfast, eating out, and eating instant food30 These are known independent risk factors for NAFLD.31 In short, long working hours may increase the risk of developing NAFLD, which may have increased the LFT.

Second, long working hours cause psychosocial job stress, and stress can affect the liver. Joung et al.32 conducted several animal experiments and suggested that stress can induce an inflammatory response in the liver through certain mechanisms such as overproduction of stress hormones and activation of the sympathetic nerve. Vere et al.9 reported that psychosocial stress can adversely affect the course of liver disease, and Chida et al.33 reported that the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system play a key role in this process. It has been reported that these reactions may disrupt the inflammatory response,34 increase fat accumulation35 and inhibit regeneration in the liver.36 In addition, a cohort study conducted by Russ et al.37 found that mental stress increased the risk of death from liver disease, and a dose-response relationship was observed, suggesting that psychosocial stress caused by long working hours may partially contribute to liver damage. However, current study did not perform a quantitative stress evaluation; hence, it was not possible to analyze the association between stress and liver damage.

Third, long working hours may increase the risk of heavy drinking,7 which may adversely affect the liver. This is presumed to be because drinking reduces the level of stress that can occur in a work environment, such as long working hours, which is so called tension-reduction hypothesis.3839 Heavy drinking increases the risk of diseases such as alcoholic hepatitis,40 and heavy drinking itself adversely affects the LFT, and shows a dose-response relationship.41 This may result in an abnormal LFT. The analysis results of the relationship between weekly working hours and heavy drinking in male are presented in Supplementary Table 2. It was statistically significant in male working ≥ 61 hours per week than in those working 35–52 hours per week, which is thought to partially support this hypothesis.

As a result of analysis of variance analysis of the mean of LFT for each group, no significant difference was observed, but the SD was large (Supplementary Table 3). This suggests that long working hours might not simply increase LFT overall, but rather increase in certain high-risk groups. Taking this into consideration, the results of a stratified analysis in male are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. As a result, the OR of abnormal LFT increased when working for a long time for each stratification variable, but only a few cases occurred in which the OR of abnormal AST and ALT levels significantly increased at the same time. Nevertheless, the stratified analyses showed 4 findings. First, the OR of abnormal LFT was significantly increased in the group aged 40 years or older. Second, it was also significantly increased in the BMI 25 kg/m2 or higher group, further suggesting a dose-response relationship (p for trend < 0.05). It is assumed that the association is stronger in middle-aged people aged 40 years or in obese individuals Third, it was also significantly increased in worker with non-standard work schedule. Age and obesity are well-known risk factors for NAFLD42 and non-standard working schedule may disrupt circadian rhythm and affect liver homeostasis,43 suggesting that weekly working hours may affect the LFT in these high-risk groups; therefore, intervention is considered necessary in this group. Finally, considering that ALT is a more specific indicator of liver damage than AST, in pink-collar and temporary workers, the ORs of abnormal ALT increases to 2.03 (95% CI: 1.20–3.43) and 1.63 (95% CI: 1.04–2.54), respectively. This is presumed to be because a pink-collar job causes high job stress due to the exceptional amounts of emotional labor involved,44 and the temporary worker is high-risk for job stress due to job instability.45 These are all high-risk groups, and it is considered that preventive intervention is necessary.

However, no correlation was observed between long working hours and abnormal LFT in female. The reasons for this finding are not clear, but this can be explained by the following mechanisms: First, it is due to the biological protective effect of estrogen. Estrogen is known to reduce fat peroxidation46 and may exhibit anti-inflammation effect.47 This action can be applied as a protective action against the risk of NAFLD and an increase in inflammation caused by stress. Second, it is because of the difference between male and female in response to psychosocial stress. Alcohol consumption due to psychological job stress is known to show a gender difference.4849 It is presumed that this is because male try to relieve stress by drinking alcohol, while female relieve it by searching for social support or talking with a partner.50 Third, long working hours may act as promoters of abnormal LFT, rather than as an initiator. In general, obesity rates are higher in male than in female, which is closely linked to increased LFT. Likewise, the female who participated in this study were relatively younger than male, had lower BMI levels, lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome, and lower prevalence of heavy drinking; therefore, they are a relatively healthy group with a lower risk of abnormal LFT (Supplementary Table 5). This is presumed to potentiate the risk of abnormal liver enzymes in the high-risk group, rather than simply affecting the liver enzymes. However, these interpretations are limited, and further studies are required.

A consistent significance was observed for male working more than 60 hours per week, whereas no significant results was observed between 53–60 hours per week. In July 2018, with the enforcement of the Korea Labor Standards Act, the maximum statutory working hours per week was reduced from 68 hours to 52 hours. As a result, the number of people working more than 60 hours per week has decreased. However, in the case of exceptional industries such as health care and transportation, if the flexible work system is implemented, and in workplaces with fewer than 5 employees to which the Labor Standards Act does not apply, those who work in the relevant industry may work more than 60 hours per week. So health management for them is necessary. Longitudinal studies with different populations or larger sample sizes are also needed.

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, there is a risk of recall bias because working hours were measured using self-reported questionnaires. However, recent studies found that standardized self-administered questionnaires were not inferior to the measurement of actual working hours.5152 Second, it was evaluated only based on simple LFT values, and the presence of clinical diseases was not sufficiently considered. However, in this study, participants with a history of viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer were excluded; moreover, ALT itself has a close correlation with NAFLD and has predictive power.53 Third, because cross-sectional studies conducted for 11 years were integrated, the characteristics of the participants may be different by year. However, even if the characteristics of the participants change every year, we assumed that the relationship between long working hours and abnormal liver enzyme levels would not change. Fourth, since hepatitis B or C, which have a large burden of disease on the liver,54 was excluded from the study design stage, this study has limitations in consideration of the above diseases. Although working hours may be linked to the risk of viral hepatitis, the discussion was excluded because it is beyond the subject of this study. Finally, the temporal relationship between weekly working hours and abnormal LFT could not be identified. However, in general, liver damage causes fatigue55; because of this, people try to avoid working long hours. Hence, the possibility of reverse causation is thought to be low. Nonetheless, selection would probably lead to an underestimation of the true risk; therefore, a longitudinal study of the association between weekly working hours and abnormal LFT is needed in the future.

On the contrary, this study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to analyze the relationship between long working hours and abnormal LFT in a representative Korean population. In addition, the stratification analysis provided information on high-risk populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Compared with the 35–52 hours working group, no significant increase in LFT was observed in the 53–60 hours working group, but it did increase significantly in the ≥ 61 hours working group. Nevertheless, it would be premature to conclude that long working hours is an independent risk factor for liver disease, until there is sufficient evidence to confirm these results. The results of stratification analysis suggest that long working hours could affect the liver and emphasize the need for intervention in high-risk groups, such as those aged > 40 years, obese individuals, worker on non-standard work schedule, pink-collar workers, or temporary workers. To reduce overwork-related liver diseases, compliance with appropriate working hours is necessary, especially in high-risk groups. In order to develop the best preventive strategies, more research on this topic is needed in order to clearly understand the mechanism by which long working hours affect the liver.

Acknowledgements

We thank the team of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) and Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) for providing the original KNHANES data. The authors are solely responsible for the contents of the present study, and they do not necessarily represent the official views of the KDCA.

Notes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors contributions:

Conceptualization: Kang MY.

Data curation: Song JH.

Formal analysis: Song JH.

Validation: Kang MY.

Visualization: Song JH.

Writing - original draft: Song JH.

Writing - review & editing: Lee DW, Kim HR, Min JH, Lee YM, Kang MY.

Abbreviations

ALT

alanine aminotransferase

AST

aspartate aminotransferase

BMI

body mass index

CI

confidence interval

DM

diabetes mellitus

HDL

high-density lipoprotein

KNHANES

Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

LC

liver cirrhosis

LFT

liver function test

LTPA

leisure-time physical activity

NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

OECD

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

OR

odds ratio

SD

standard deviation

References

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Table 1

Sensitivity analysis in men participants

Supplementary Table 2

Adjusted OR (95% CI) for heavy drinking by weekly working hours in male participants

Supplementary Table 3

Analysis of variance analysis between weekly working hour and abnormal LFT in male participants

Supplementary Table 4

Subgroup analysis of abnormal LFT by weekly working hours in male participants

Supplementary Table 5

General characteristics of the participants