Analysis of self-reported mental health problems among the self-employed compared with paid workers in the Republic of Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background

As self-employed workers are vulnerable to health problems, this study aimed to analyze mental health problems and sleep disturbances among self-employed workers compared with paid workers in Korea.

Methods

A total of 34,750 workers (23,938 paid workers and 10,812 self-employed workers) were analyzed from the fifth Korean Working Condition Survey, which included 50,205 households collected by stratified sampling in 2017. To compare mental health problems and sleep disturbance among self-employed workers and paid workers, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed.

Results

The odds ratio in self-employed workers compared with paid workers was 1.25 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.09–1.42) for anxiety, 1.11 (95% CI: 1.04–1.17) for overall fatigue, 1.11 (95% CI: 1.04–1.20) for difficulty falling asleep, 1.10 (95% CI: 1.02–1.18) for difficulty maintaining sleep and 1.24 (95% CI: 1.16–1.32) for extreme fatigue after waking up.

Conclusions

Self-employed workers in Korea have a higher risk of self-reported mental health problems and sleep disturbances than paid workers. Further studies with a longitudinal design and structured evaluation are required to investigate the causal relationship between health problems and self-employment.

BACKGROUND

According to the International Labour Organization, self-employed workers are people who operate their own business or work with one or several partners or in cooperatives. Their remuneration directly depends on profits derived from the goods and services produced and provided.1 Self-employment includes both the concept of an employer running a business with one or more paid employees and the concept of a person himself/herself running a business; it can be defined as a process in which a person employs himself or herself and can hire others.

According to the statistics of self-employed workers in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in 2020, the United States accounted for 6.3%, Canada 8.3%, European Union (EU) 14.7%, and the Republic of Korea (henceforth, Korea) 24.6%.2 Korea is the sixth among the OECD countries considering the percentage of self-employed people. Though the percentage of self-employed workers in the country continued to decline from 2012 until 2020, they still account for over 20% of all workers.3 Since self-employed workers are legally regarded as business owners, they are not subject to basic health insurance coverage, except for employment insurance or industrial accident compensation insurance.45 Moreover, unlike paid workers, self-employed workers should be held accountable for all possible risks at work. Thus, are considered to be more vulnerable to health problems.6789

Studies on mental health problems and sleep disturbances have mostly focused on paid workers rather than on self-employed workers. Mental health problems and sleep disturbances are global problems that must be addressed. In 2016, approximately 17% of the population in EU countries experienced mental health problems. Anxiety disorder was the largest of such problems with 5.4% of the EU population, followed by depression with 4.5% of the population.10 In the United States, an estimated 50–70 million people suffer from sleep disorders and costs billions of dollars every year.11 Poor mental health and sleep quality are shown to be associated with many chronic health problems, including diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases.1213141516 Furthermore, it can also lead to lowering their physical and psychological life due to reduced productivity and increased work-related disability.1718192021

Few studies have considered the problems of self-employed workers compared with those of paid workers in Korea. Therefore, we aimed to assess mental health problems and sleep disturbances in self-employed workers compared with paid workers in the country.

METHODS

Data source and study population

We analyzed data collected from the fifth Korean Working Conditions Survey (KWCS) conducted by the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (KOSHA). The survey provides basic data on workers’ health, working conditions, working hours, and workplace environments, and its methods and structure are based on the European Working Conditions Survey.22 The population of the KWCS included a representative sample of current Korean workers aged ≥ 15 years selected from across the country through multistage systematic cluster sampling. All participants agreed to enroll in further scientific research and were assigned random numbers to protect their anonymity.23

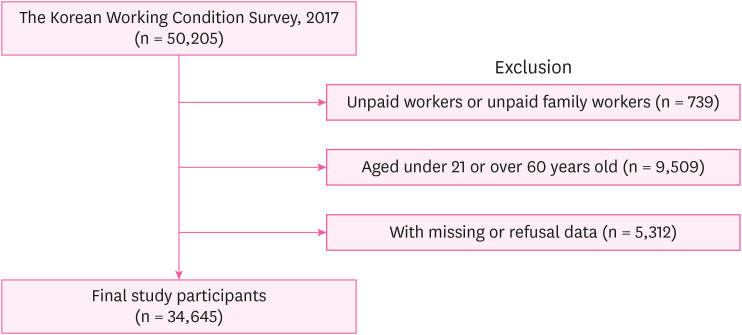

In the fifth KWCS, 50,205 workers participated. We extracted data on adult participants aged 21–60 years, which represent the general working population, and restricted them to paid and self-employed workers. Thus, data from 34,645 participants were included in this study after excluding those aged < 21 or > 60 years (n = 9,509), who were unpaid workers or unpaid family workers (n = 739), and who missed or refused (n = 5,312) (Fig. 1).

Main variables

A self-report questionnaire was used to ask the participants whether they had mental health problems or experienced sleep disturbances. Mental health problems were assessed based on whether the participants answered yes to the following questions: “Over the last 12 months, did you have depressive symptoms?”; “Over the last 12 months, did you have anxiety?”; and “Over the last 12 months, did you have fatigue symptoms?” Those who answered positively were defined as having depressive symptoms, anxiety, and overall fatigue. Those who answered “no” to the questions were considered asymptomatic, and the respondents who answered “don’t know” were excluded from the analysis. Questions about sleep disturbance included (1) difficulty falling asleep, (2) difficulty maintaining sleep, and (3) extreme fatigue after waking up. The participants could select the following options: “every day,” “several times a week,” “several times a month,” “rarely,” “none,” “no comments,” or “denial.” Those who answered that they experienced sleep disturbances at least several times a month were considered to have experienced sleep disturbances.

Covariates

Potential confounding variables included sex, age, education level, household income, occupational classification, enterprise size, and weekly working hours. Age was divided into four categories: 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, and 51–60 years. Educational level was categorized as middle school or below, high school, or college or above. Monthly income was divided into the following four groups considering the intervals of 1,000 U.S. dollars: < $1,000, $1,000–$2,000, $2,000–$3,000, and ≥ $3,000. The KWCS data investigated 10 occupation types and surveyed soldiers based on the Korean Standard Occupational Classification (6th revision). Occupations were classified into four categories: white-collar (managers, professionals, technicians, semi-experts, and office workers), service and sales (service workers and sales workers), green-collar (skilled agricultural and fishery workers), and blue-collar (functional operators and relevant functional workers, equipment, machinery handlers, assembly workers, and simple laborers). Enterprise size was classified into four categories based on the number of workers: one person, 2–4 people, 5–49 people, and ≥ 50 people. Working hours were classified into two categories: 52 hours and < 52 hours per week and > 52 hours per week (defined as long working hours).

Statistical analysis

We performed chi-square tests to compare the baseline characteristics of the paid and self-employed workers. We used weighted analysis to show the weighted prevalence rate using the weighted number of people and the proportion of mental health problems, as well as p-values. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for self-reported mental health problems and sleep disturbance in self-employed workers were calculated using a fully adjusted multiple logistic regression model. For the adjusted logistic model, potential confounders were selected based on previous studies and eliminated using backward stepwise selection. Statistical significance was set at a p < 0.005. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Gil Medical Center, Gachon University, approved this study (IRB No. GFIRB2019-278).

RESULTS

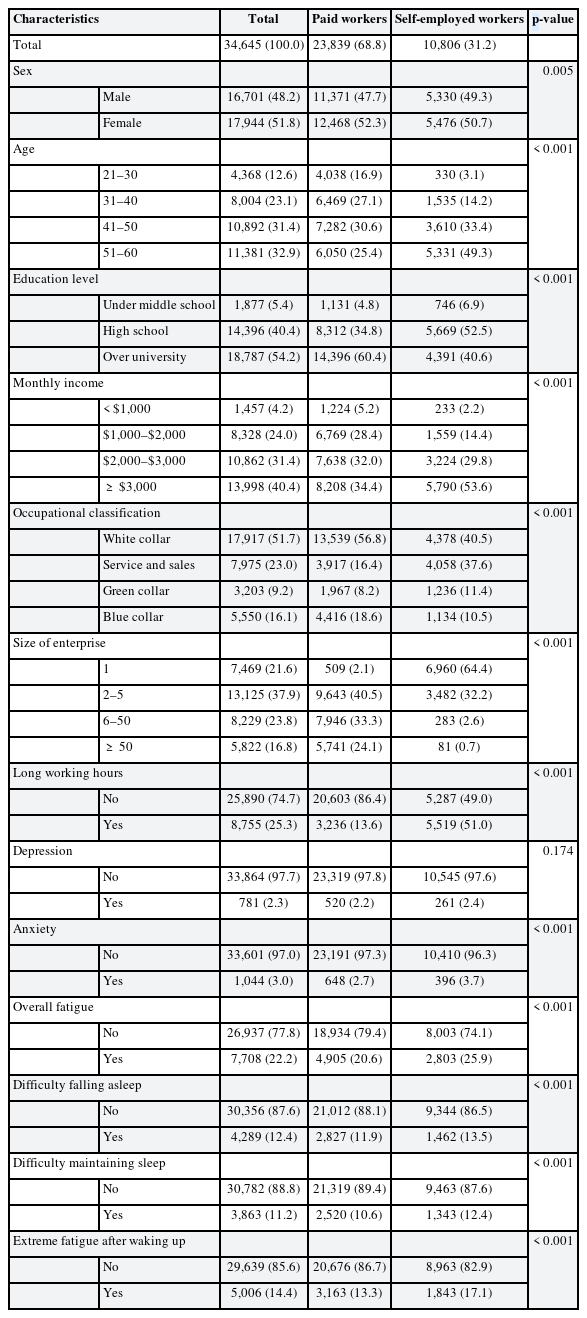

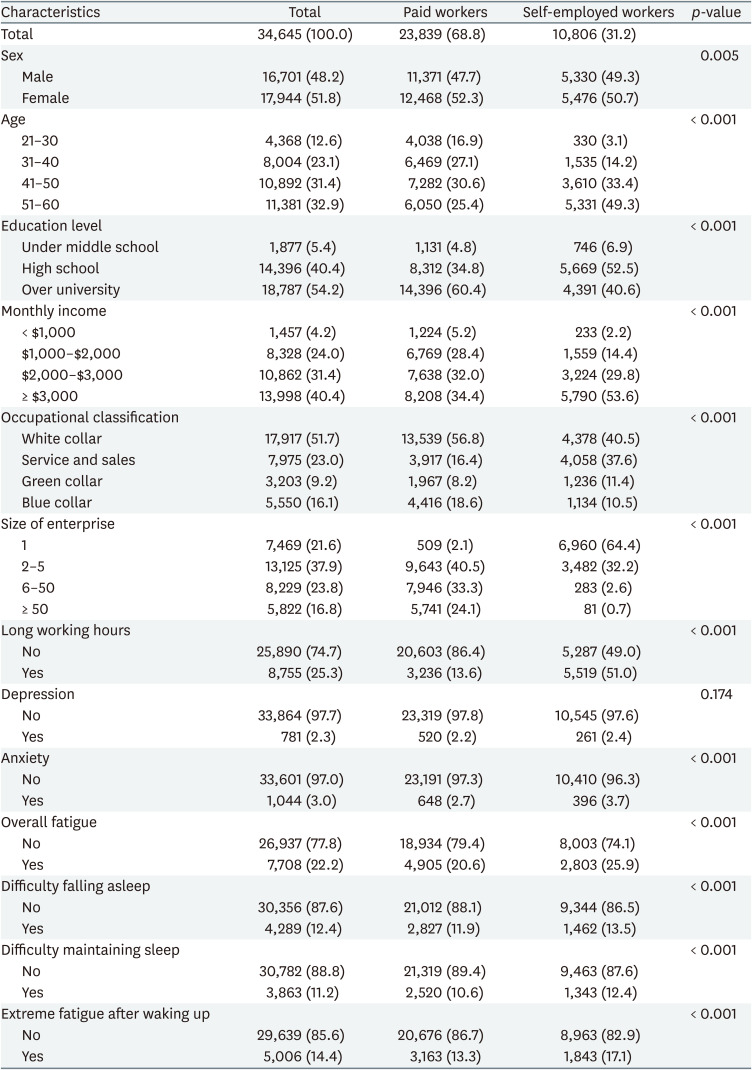

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of 23,839 paid workers and 10,806 self-employed workers. Among the study participants, women (51.8%), workers aged 51–60 years (32.9%), university graduates (54.2%), and those with a monthly income ≥ $3,000 (40.4%) accounted for a high percentage of paid and self-employed workers. In terms of working characteristics, 51.7% of paid workers were engaged in white-collar occupations, and this percentage was 40.5% among self-employed workers. Unlike paid workers, lone workers accounted for the highest percentage (64.4%) of self-employed workers. The percentage of those who work more than 52 hours a week accounted for 13.6% of the paid workers and 51.0% of the self-employed workers.

Self-reported mental health problems (depression, anxiety, and overall fatigue) were higher in self-employed workers than in paid workers. Sleep disturbance, which was evaluated as “difficulty falling asleep,” “difficulty maintaining sleep,” and “extreme fatigue after waking up,” showed a higher percentage of self-employed workers than paid workers. Sex, education level, monthly income, occupational classification, size of the enterprise, long working hours, depression, anxiety, overall fatigue, difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and extreme fatigue after waking up showed statistically significant differences between paid and self-employed workers.

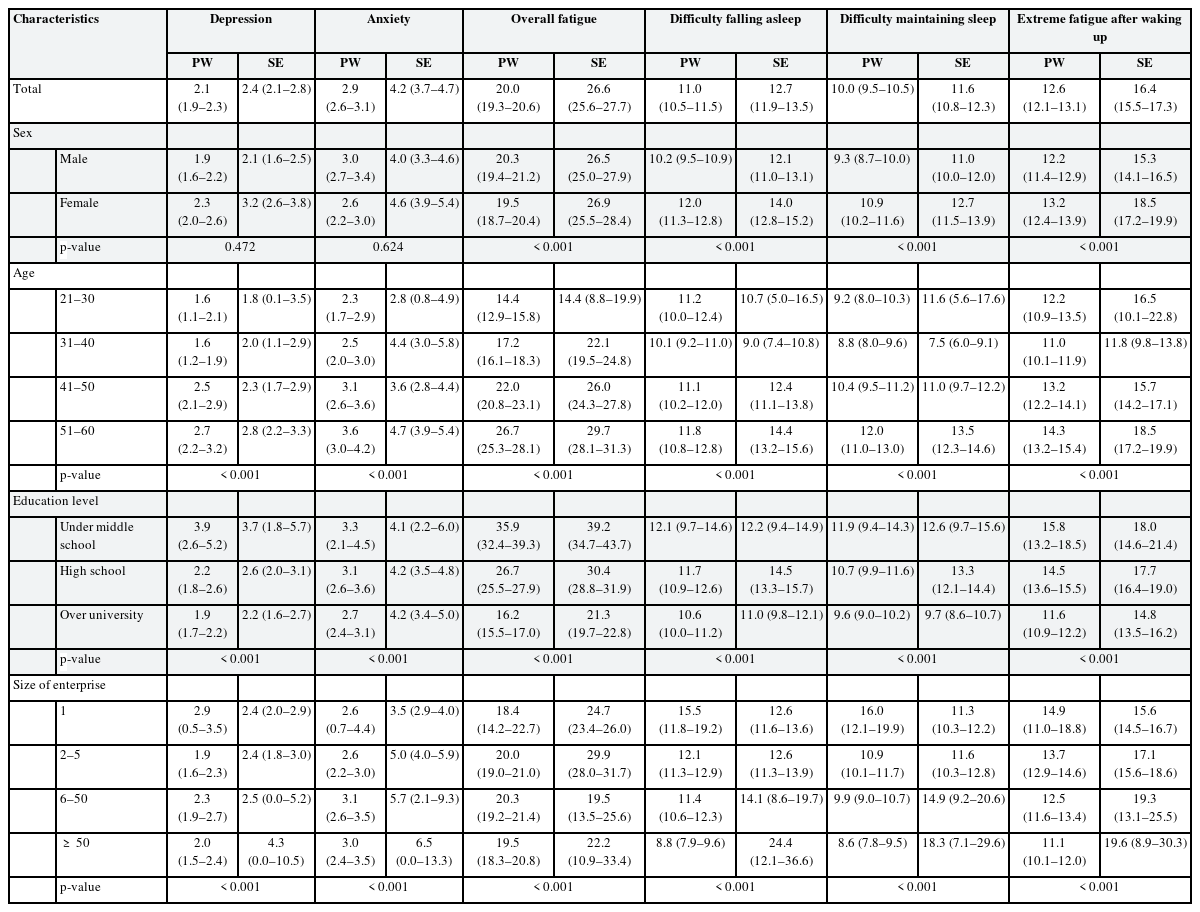

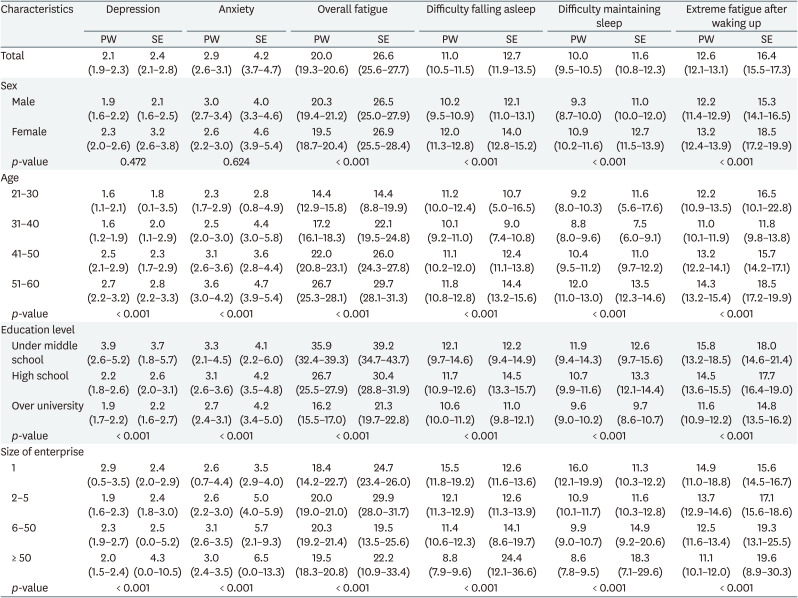

Table 2 shows the weighted prevalence rates of self-reported mental health problems and sleep disturbance. The overall weighted prevalence rates of mental health problems and sleep disturbances were higher in self-employed workers than in paid workers. Among self-employed workers, the weighted prevalence rate of depression was high in females aged between 51 and 60, those who were under middle school, and those who ran enterprises with 50 or more employees. For anxiety, the weighted prevalence rate was high in females, those were between 51 and 60 years, those with high school education or above, and those who ran enterprises with 50 or more employees. For overall fatigue, the weighted prevalence rate was high in females between 51 and 60 years, those who were under middle school, and those who ran enterprises with two to five employees. For difficulty falling asleep and difficulty maintaining sleep, the weighted prevalence rate was high in females between 51 and 60 years, those with high school education, and those who ran enterprises with 50 or more employees. For extreme fatigue after waking up, the weighted prevalence rate was high in females between 51 and 60 years, those who were under middle school, and those who ran enterprises with 50 or more employees.

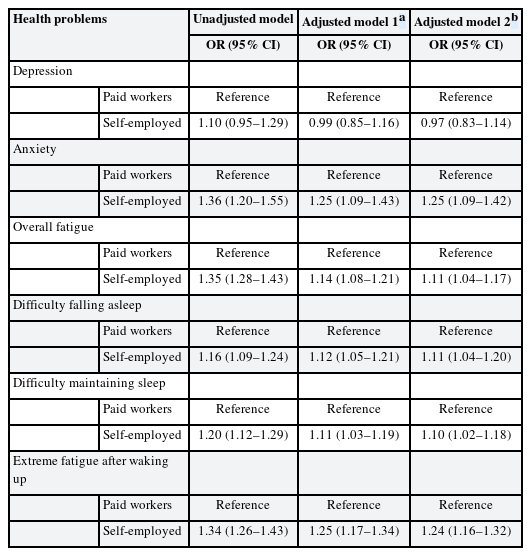

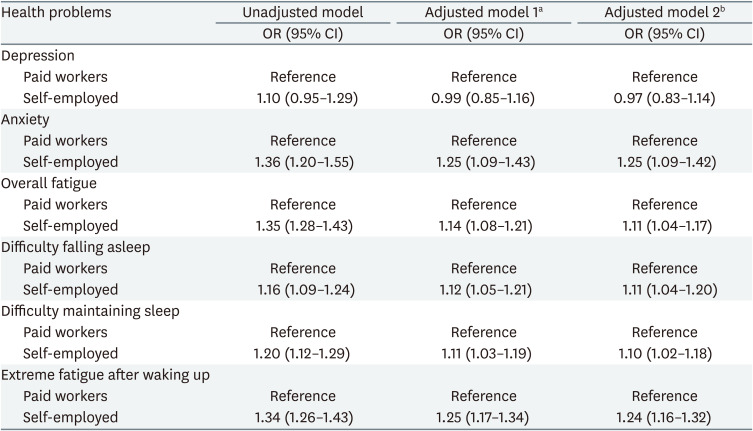

Table 3 shows the ORs (95% CI) adjusted for covariates (sex, age, education level, and size of enterprise) for self-reported mental health problems and sleep disturbances between paid workers and self-employed workers. For self-employed workers, unadjusted OR was 1.36 (95% CI: 1.20–1.55) for anxiety, 1.35 (95% CI: 1.28–1.43) for overall fatigue, 1.16 (95% CI: 1.09–1.24) for difficulty falling asleep, 1.20 (95% CI: 1.12–1.29) for difficulty maintaining sleep, and 1.35 (95% CI: 1.26–1.43) for extreme fatigue after waking up. A significant association was observed in all categories except for depression in the unadjusted model. In the adjusted model 1 which was adjusted for covariates (sex and age), OR was 1.25 (95% CI: 1.09–1.43) for anxiety, 1.14 (95% CI: 1.08–1.21) for overall fatigue, 1.12 (95% CI: 1.05–1.21) for difficulty falling asleep, 1.11 (95% CI: 1.03–1.19) for difficulty maintaining sleep, and 1.25 (95% CI: 1.17–1.34) with significant associations. In the adjusted model 2 which was fully adjusted for covariates (sex, age, education level, and size of enterprise), OR was 1.25 (95% CI: 1.09–1.42) for anxiety, 1.11 (95% CI: 1.04–1.17) for overall fatigue, 1.11 (95% CI: 1.04–1.20) for difficulty falling asleep, 1.10 (95% CI: 1.02–1.18) for difficulty maintaining sleep, and 1.24 (95% CI: 1.16–1.32) with significant associations.

DISCUSSION

We used 2017 KWCS data to examine the risk of mental health problems and sleep disturbances among self-employed workers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate mental health problems and sleep disturbances among self-employed Korean workers. The results of this study suggest that mental health problems and sleep disturbances have a higher prevalence in self-employed workers than in paid workers.

This study showed that the prevalence rate was consistently high among self-employed workers who were female, those who were between 51 and 60 years, and those who ran an enterprise with 50 or more employees, except for the education level. In Korea, women often handle childcare and housework alone; therefore, mental health problems and sleep disturbances are thought to be more prominent among self-employed workers. In particular, individuals aged 51 to 60 and females are seen to be more vulnerable to mental health problems due to social inequality.24 Self-employed workers who ran enterprises with 50 or more employees were found to be at higher risk of mental health problems, except for overall fatigue and sleep disturbance. These problems can be thought of as a result of responsibility and stress from business operations rather than the autonomy and flexibility of the self-employed.

Our study found that self-employed workers were at a higher risk of mental health problems such as anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disturbance than paid workers. Self-employed workers are more stressed than paid workers, caused by the pressure of their business and the responsibility for their employees, which can lead to the mentioned health problems.25 Furthermore, high levels of stress can increase cortisol levels in the long term, leading to up-regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and degradation of the immune system, which makes self-employed workers more vulnerable to diseases.26 The mechanism by which stress causes sleep disturbance is still unclear; however, the quality of sleep is considered to be closely related to stress.2728 In the case of depression, high risk has not been shown in self-employed workers compared with paid workers, which leads to the interpretation of the mechanism by which anxiety is induced prior to depression and of the advantages of self-employment such as autonomy and flexibility, which serve as a buffer against stress, resulting in low risk.2930

Sleep disturbance is likely to be linked to increased cortisol levels, as insomnia is considered to be caused by the excessive activation of the arousal system.3132 Furthermore, self-employed workers usually have longer working hours than paid workers, which causes fatigue—known as a major result of stress along with increased catecholamine excretion.3334 In addition, our study also showed that the percentage of long working hours in self-employed workers is higher than that in paid workers, which is attributable to the long hours of work and stress.

The results of this study are consistent with those of previous studies showing that self-employed workers experience mental health problems and sleep disturbances. A French study examined the health conditions of self-employed workers in the foodservice industry compared with other paid workers. The prevalence of sleep disturbance among self-employed workers was significantly higher (37% vs. 24%), as they were more mentally stressed (57.5% vs. 41.6%).35 This study suggested that although the area of workers is limited to the foodservice industry, mental stress and sleep problems pose a high risk to self-employed workers. In addition, a study from Sweden showed that among mental health problems, fatigue increased, which matched our findings on self-employed workers.36 A study that used a systematic analysis of mental health problems encountered by self-employed workers showed inconsistent results in several studies, while cross-sectional studies in the United States, Australia, and Europe showed lower or similar prevalence estimates for self-employed workers compared with paid workers.37 However, although cross-sectional research is limited, the prevalence rate of mental problems among self-employed workers in Korea was higher than that of paid workers, which was consistent with our results.

Self-employed workers are assumed to be more autonomous and flexible than other employees, and for this reason, they are expected to show less work-related stress and high job satisfaction through high job control.38 In the case of the Swedish study, despite low income and long working hours, self-employed workers have high job satisfaction.36 However, their mental health problems, which are especially prominent in Korea, can be attributed to inadequate socio-political protection, such as health insurance and pension plans, rather than job control or satisfaction.3940 Self-employed workers are considered employers, not workers, and are not fully protected by the Occupational Safety and Health Act of Korea. Furthermore, they are often blind spots because of their small and unofficial sectors, and they do not receive sufficient attention from policymakers and researchers because of limited data. Self-employed workers are essential members of society who contribute to a country’s economic growth and stabilization, and they need both research and policy attention, as well as support. Without system revision, self-employed workers’ health and safety will continue to be at potential risk. Although our study did not analyze job satisfaction, occupational status (regular, temporary, daily), existing health problems, spouse’s working hours, housekeeping, length of service, and flexibility in working hours among self-employed workers, further studies should take a closer view of institutional vulnerabilities by focusing on the aforementioned variables and compare them with these variables on self-employed workers in other countries or different types of workers.

This study has several other limitations. First, the obtained data were analyzed cross-sectionally, and an association between mental health problems and sleep disturbance was found in self-employed workers; however, a causal relationship could not be established. Further longitudinal studies are required to confirm this causal relationship. Furthermore, this study lacked structured measurements to assess the degree of mental health problems and sleep disturbance due to the limitations of the nature of the data. Therefore, objective evaluation tools should be used to overcome these limitations in future studies.

This study has several strengths. Self-employed workers in the KWCS population were systematically selected by the KOSHA. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Korea to assess the prevalence and OR of mental health problems and sleep disturbance in self-employed workers compared with paid workers. Self-employed workers are vulnerable to occupational safety and health problems as employers and workers at the same time. We hope that our study will promote future research on the safety and health of self-employed workers. In addition, structured evaluation tools should be developed using longitudinal studies to identify the causality among self-employed workers.

CONCLUSIONS

Using KWCS data, this study found that self-employed workers in Korea had a higher risk of self-reported mental health problems and sleep disturbance than paid workers. Further studies with a longitudinal design and structured evaluation are needed to discuss ways to improve self-employed workers’ health.

Notes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions:

Conceptualization: Lee Y, Lee W.

Data curation: Lee Y, Lee J, Han E.

Formal analysis: Lee Y, Lee J, Kim UJ.

Project administration: Lee W.

Supervision: Lee W.

Methodology: Kang SK, Lee W.

Software: Lee W.

Investigation: Lee Y, Ham S, Choi WJ, Kang SK.

Validation: Ham S, Choi WJ, Kang SK.

Visualization: Lee Y.

Writing - original draft: Lee Y.

Writing - review & editing: Kang SK, Lee W.

Abbreviations

CI

confidence interval

EU

European Union

KOSHA

Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency

IRB

Institutional Review Board

KWCS

Korean Working Conditions Survey

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OR

odds ratio

PW

paid workers

SE

self-employed workers