Transnational ties with the home country matters: the moderation effect of the relationship between perceived discrimination and self-reported health among foreign workers in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background

Little attention has been paid to the relationship between perceived discrimination and self-rated health (SRH) among foreign workers in Korea. Transnational ties with the home country are known to be critical among immigrants, as they allow the maintenance of social networks and support. Nonetheless, as far as we know, no studies have examined the impact of transnational ties on SRH itself and the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH, which the current study tries to examine.

Methods

Logistic regression analyses were conducted using the 2013 Survey on Living Conditions of Foreign Workers in Korea. Adult foreign workers from different Asian countries (n = 1,370) participated in this study. The dependent variable was good SRH and the independent variable was perceived discrimination. Transnational ties with the home country, as a moderating variable, was categorized into broad (i.e., contacting family members in the home country) vs. narrow types (i.e., visiting the home country).

Results

Foreign workers who perceived discrimination had a lower rate of good SRH than those who did not perceive discrimination. Broad social transnational ties moderated the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH; narrow social transnational ties did not.

Conclusions

In line with previous studies, an association was found between perceived discrimination and SRH. Broad social transnational ties can be a good source of social support and buffer against the distress of perceived discrimination.

BACKGROUND

Discrimination is a serious social and health disparity issue that has been shown to have an association with health, including mental health, poor self-rated health (SRH) and higher prevalence of chronic conditions and other risky health behaviors.1234 Both direct and indirect relationships have been shown between perceived discrimination and SRH.5 Immigrants and foreign workers, who are racially and culturally different from the native population, are more likely to experience perceived discrimination, both institutionally (e.g., social policies and structural inequalities) and interpersonally (e.g., physical or verbal abuse).67 Different factors, including acculturation, coping styles, social support, and employment status, were identified as having moderating effects on immigrants’ perceived discrimination and health.8910

Korea (hereafter Korea), which has traditionally been a homogeneous society, has become more racially diverse in recent years, with an increasing number of immigrants, and the population is projected to grow further.1112 Most immigrants migrate for economic reasons, that is, to find work in Korea and female immigrants migrate primarily to enter an international marriage, that is, to marry a Korean man in a rural area.1314 Foreign workers are willing to accept labor-intensive, difficult and even dangerous jobs that domestic workers refuse to do; thus, they are more prone to experience perceived discrimination.13 The past decade has seen a larger proportion of male immigrants than female immigrants entering Korea.15 It has been reported that immigrants are more likely to experience racism; a survey conducted by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea found that 7 out of ten foreign residents had experienced perceived discrimination.16 It is possible that because of the collectivist culture, Koreans are more likely to discriminate against foreigners, such as by their skin colors.11

A study from Korea that examined the perceived discrimination and SRH in the general Korean population in urban areas of Korea found that experiences of perceived discrimination are significantly associated with poor SRH even among the general Korean population.4 This finding is surprising, as Korea is viewed as a predominantly monocultural society with a collectivistic social tradition.13 Some studies conducted in Korea have examined perceived discrimination and its relationship with mental and oral health,17181920 but to our knowledge, only a few have examined the relationship with SRH. Moreover, even less focus has been given to immigrant workers, their perceived discrimination and SRH.

Social support, including instrumental, emotional, and informational support, has been identified as a critical factor that influences health,212223 which can be maintained through transnational ties. Strong maintenance of transnational ties with the home country has been made easier for immigrant workers and foreigners because of advancements in technologies facilitating communication and connections with the home country (e.g., text messaging and emails) and cheaper airfares.2425 While transnational ties have been discovered in various spheres, including the political, economic, social, and medical spheres,26272829 researchers have categorized transnational ties into broad and narrow types according to these different spheres.30313233 Social transnational ties are also divided into narrow and broad transnational ties.31 Narrow transnational ties include maintaining home-country relationships by physically visiting the home country, whereas broad transnational ties involve contacting people, such as families and friends, in the home country.31

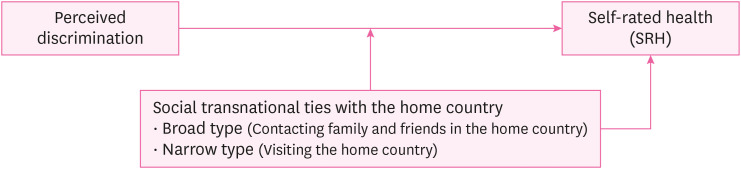

To our knowledge, hardly any studies have examined the effect of transnational ties on perceived discrimination and SRH. Thus, this study aims to examine whether there is a relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH among immigrant workers in Korea and whether transnational ties moderate this relationship. The conceptual framework of the current study is presented in Fig. 1.

METHODS

Data

We analyzed the Survey on Living Conditions of Foreign Workers, 2013 by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Migration Research & Training Centre in Korea, which was distributed by the Korea Social Science Data Archive.34 The data included information about foreign workers who came to Korea under the employment permit system and Korean-Chinese workers employed under the visiting employment system. The employment permit system allows businesses suffering from a shortage of labor from an inability to find Korean workers to legally hire foreign workers under certain requirements. The system is divided into a normal employment permit system, where individuals from 15 countries, including the Southeast Asian countries, can be hired on an E-9 visa, and a special employment permit system, where overseas Koreans with foreign citizenship (e.g., Korean-Chinese) can be hired on an H-2 visa. They are granted the right to work for 3 years, with the possibility of an extension for an additional year and ten months in the case of re-employment. In total, the employment permit system allows up to 4 years and ten months of employment.

In the current study, we excluded “Joseonjok” (or Korean-Chinese) foreign workers, the ethnic Koreans with Chinese nationality because most included foreign workers have a different visa status (E-9) than ethnic Koreans from China (H-2), and they might have different characteristics from Korean-Chinese workers who share the language and culture. The survey questionnaires included sociodemographic characteristics, the process of entry and exit, employment status, working conditions, daily life, and social relations. Initially, 1,370 individuals participated in the survey.

Measures

The dependent variable used in this study was SRH, which was measured on a Likert scale with the following question: “How do you rate your overall health?” 1) very good; 2) good; 3) fair; 4) poor; 5) very poor. We recoded SRH into 2 categories: poor (poor and very poor, coded as 0) vs. good (very good, good, and fair, coded as 1).

The main independent variable is perceived discrimination, which was measured with the following question: “Have you ever been treated differently because you were a foreigner while living in Korea?” The possible answers were “no” and “yes.” Additionally, social transnational ties with the home country were measured in 2 ways. On the one hand, the broad social transnational ties were measured with the following question: “On average, how often do you text/message (Kakao Talk, Facebook, etc.) your family, relatives, and friends in your home country?” The available answers were “more than once per day,” “more than once per week,” “more than once per month,” “less than once per month,” and “not at all.” On the other hand, the narrow social transnational ties with the home country were measured to determine how often the survey participants had visited their home country since coming to Korea on an E-9 visa (with possible answers of “never,” “once,” “twice,” “3 times” or “more”).

Control variables included age (younger than 25 years old, 25–29 years old, 30–34 years old, 35–39 years old, and 40 years old or older), sex (male vs. female), nationality (Vietnam, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, Philippines, or Other, which included Mongolia, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Uzbekistan, China, Kyrgyzstan, and Pakistan), marital status, educational attainment (middle school graduate or less educated, high school graduate, 2-year college graduate, and 4-year college graduate or graduate school graduate). In addition to these sociodemographic characteristics, years in Korea (continuous years) and Korean language proficiency (speaking; very poor, poor, fair, good, very good) were included as control variables.

Analysis

We conducted logistic regression35 to examine the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH. Additionally, we examined whether social transnational ties with the home country moderated the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH by adding an interaction36 between perceived discrimination and social transnational ties (both broad and narrow). All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 15.0 (StataCorp LLC., College Station, TX, USA) and the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Ethics statement

Although the study used publicly available secondary data, it was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Sungkyunkwan University (IRB #2021-10-001).

RESULTS

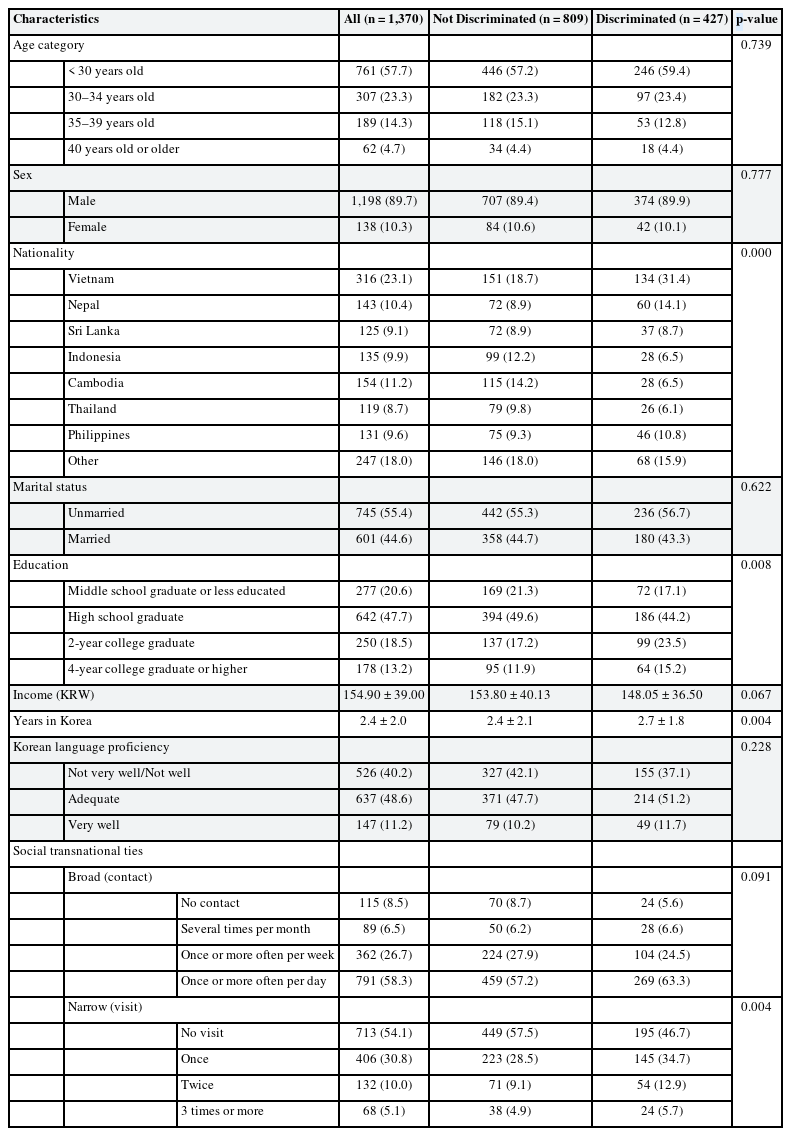

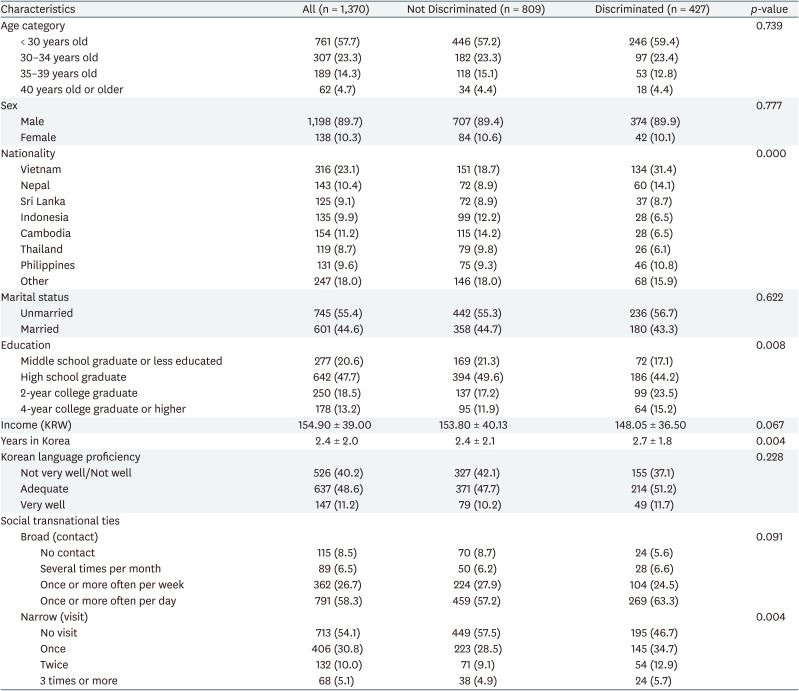

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants. Of the participants, slightly more than a half (57.7%) were younger than 30 years old, about a quarter (23.3%) were 30–34 years old, and about one fifth were 35 years old or older. Most participants were male (89.7%). Vietnamese participants comprised the largest group (23.1%), followed by participants from Cambodia (11.2%), Nepal (10.4%), Indonesia (9.9%), the Philippines (9.6%), and Sri Lanka (9.1%). Less than half (44.6%) were married and slightly less than half were high school graduates (47.7%). Regarding social transnational ties, the broad type occurred more frequently than the narrow type; more than half of the participants (54.1%) had never visited their home country during their stay in Korea under E-9 visa status, whereas only 8.5% reported that they had never contacted their family members or friends in their home country. More than a quarter (26.7%) of the participants maintained the broad type of social transnational ties once or more frequently in a week, and more than half of the participants (58.3%) maintained the broad type of social transnational ties more than once per day.

Several characteristics (i.e., nationality, education, and social transnational ties) were found to differ between participants who perceived discrimination and those who did not. For example, participants from Vietnam reported a higher rate of perceived discrimination than participants from other countries. The more educated respondents were more likely to report perceived discrimination than their less educated counterparts. Additionally, the percentage of more educated respondents was higher among participants who maintained a higher degree of social transnational ties with their home country, both broad and narrow, than those who maintained a lower degree of ties.

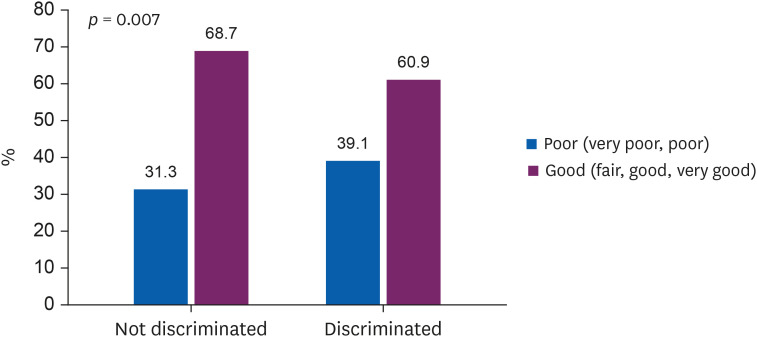

Perceived discrimination and SRH

Fig. 2 shows the negative relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH. Foreign workers who perceived discrimination in Korea reported a lower rate (60.9%) of good SRH than those who perceived no discrimination (68.7%). This relationship was statistically significant (p = 0.007).

Social transnational ties, Perceived discrimination, and SRH

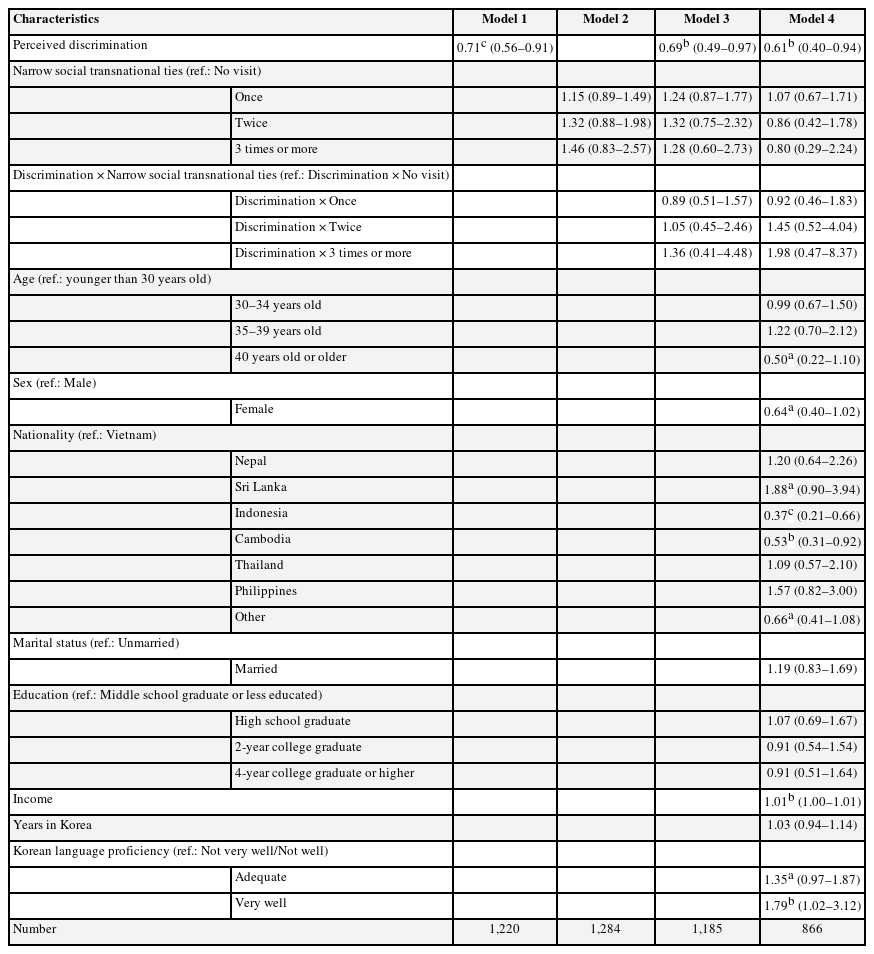

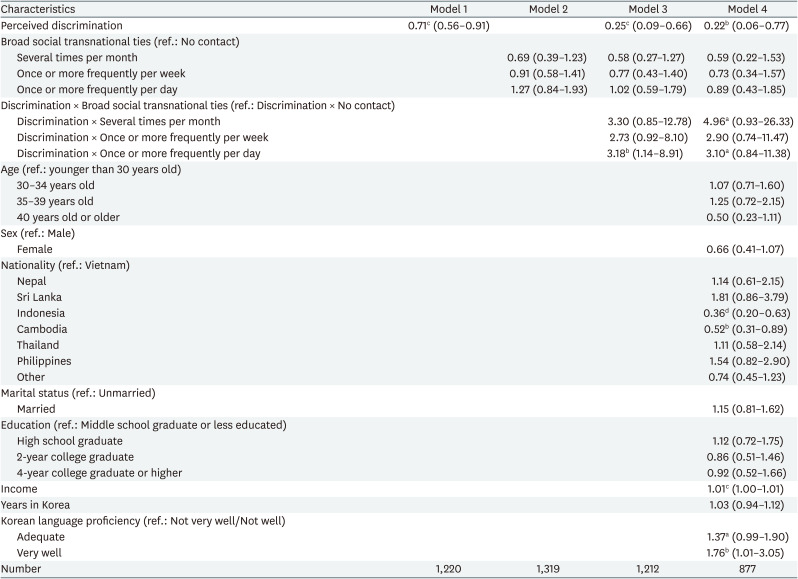

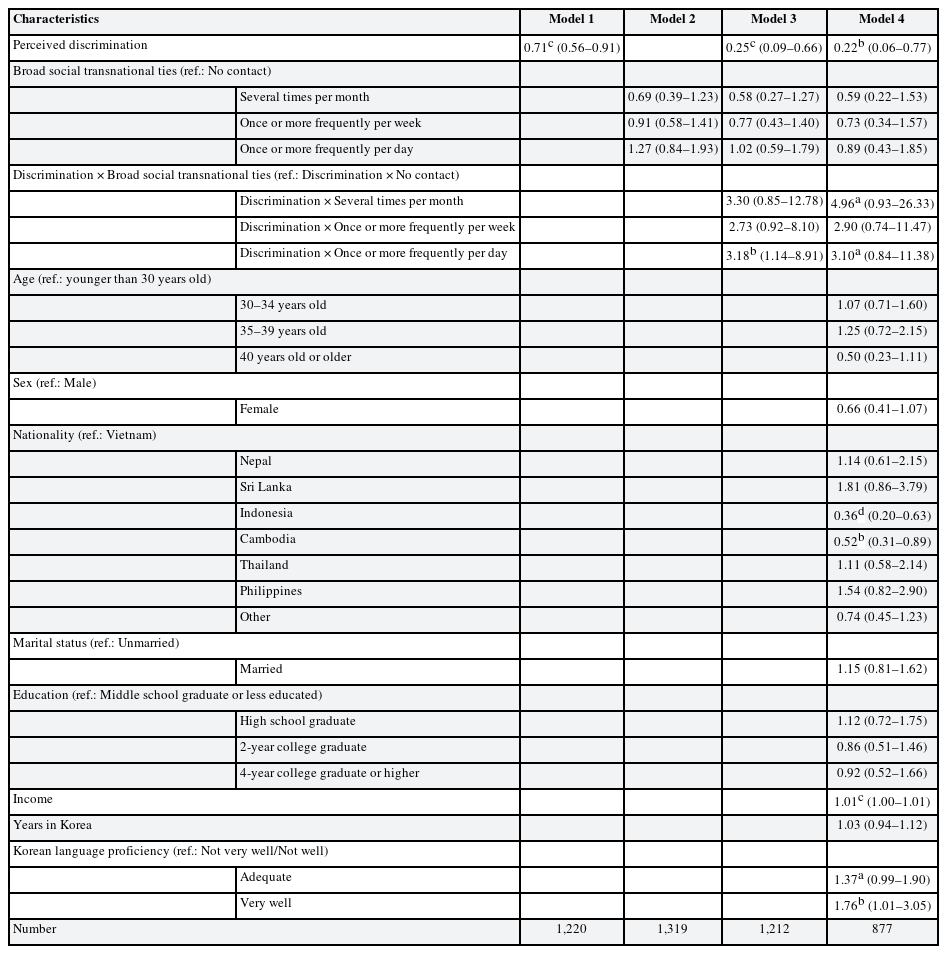

Table 2 shows the factors predicting SRH among foreign workers using logistic regression analyses with a focus on perceived discrimination and broad social transnational ties. Model 1 shows a negative relationship between perceived discrimination and good SRH (odds ratio: 0.71; 95% confidence interval: 0.56–0.91). Model 2 shows that broad transnational ties with the home country (i.e., contacting family members and friends) were not associated with SRH, while broad transnational ties moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH (Model 3). This moderation effect remained after the control variables were included in Model 4.

Adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for perceived discrimination, broad social transnational ties and good self-rated health of foreign workers

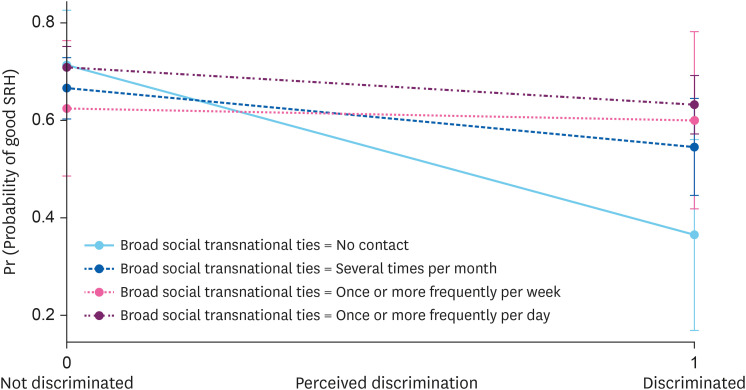

Fig. 3 shows the adjusted predictions of perceived discrimination and broad social transnational ties on good SRH. For example, participants who had the strongest social transnational ties with their home country by contacting family members and friends in the home country most frequently (e.g., once or more per day) reported the highest probability of reporting good SRH, and SRH did not differ much between the discriminated and non-discriminated groups. In contrast, participants who had not contacted their home country reported a sharper reduction in good SRH when they perceived discrimination.

Broad social transnational ties as moderator in the relationship between perceived discrimination and good SRH.

SRH: self-rated health.

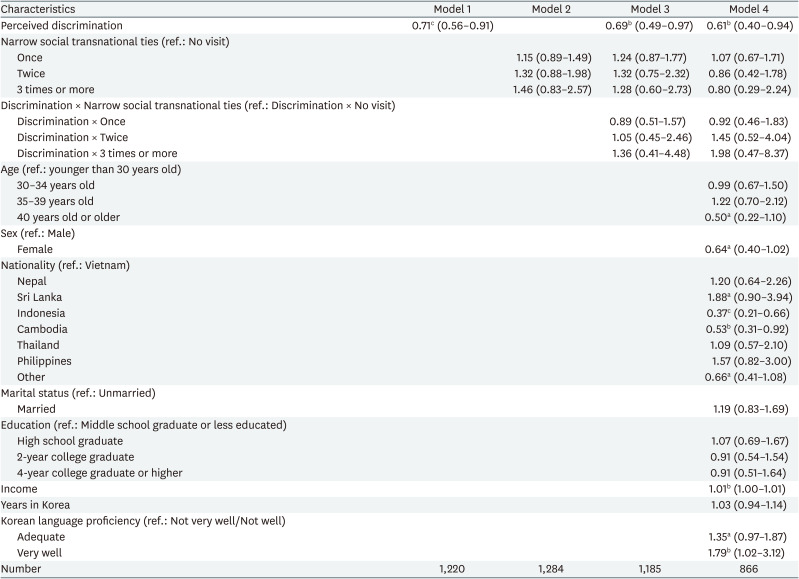

Contrary to the significant moderating effect of broad social transnational ties on the relationship between perceived discrimination and good SRH, Table 3 shows that the narrow type of social transnational ties itself did not significantly moderate the relationship among foreign worker participants (Model 2) and when perceived discrimination was added in Model 3 and when control variables (e.g., age, sex, nationality, marital status, and education) were added in Model 4.

DISCUSSION

The current study examined the relationship between perceived discrimination and the SRH of foreign workers in Korea and was the first study to examine the moderating effects of broad and narrow social transnational ties as sources of social support. In line with previous findings, we found that perceived discrimination was associated with poor SRH.67 This study contributes to the literature as most studies on discrimination and health have been conducted in the USA and Europe, as these areas contain diverse groups of immigrant populations,737 but less attention has been given to newer host countries, such as Korea.38

This study also found that broad social transnational ties with the home country moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH. Individuals generally maintained strong social transnational ties with their home countries, as more than half of the participants contacted their home countries more than once per day. Such social transnational ties were channeled to receive more social support, particularly emotional support, from families and friends in the home country, which became a source of protection from discrimination. This supports the stress-buffer model, in which stronger transnational ties act as a buffer and as a source of social support, enabling a person to feel healthier, even after facing discrimination, which is in line with previous studies.383940 A study of foreign workers in Korea found a similar outcome, whereby emotional support from the same ethnic group was associated with depressive symptoms and moderated the effect of perceived discrimination on their symptoms of depression.38 Although that study only examined social support of immigrants from the same ethnic background in Korea and did not examine transnational ties with their home countries, it shows the importance of co-ethnic support on immigrants’ health.

In this study, broad transnational ties, which allow for more emotional support, were significant, whereas narrow transnational ties were not. Rather than having support as a one-time event, it suggests that maintaining social ties with the home is critical for receiving daily support, which can be reassuring and sufficient for overcoming discrimination. Although this is not the same situation, a qualitative study of cancer patients living under high mental and physical distress reported that social support from caregivers provided them with meaning in life and gave them a reason to continue to live.23 Moreover, a previous study on Asian Americans found that perceived emotional support from family buffered the stress of everyday discrimination and protected mental health, but regularly talking on the phone and meeting up with family did not.39

Previous studies from different countries also support the findings. A recent study of immigrants in the Netherlands found that having more social transnational ties with home countries was associated with higher levels of psychological well-being, mainly life satisfaction, than co-ethnic social ties in the host country.41 Another study from Finland also found that active social support with individuals in home countries had a protective effect on the psychological well-being of immigrants from 3 different countries.42 In a study of migrants in Shanghai, China, which also found a similar outcome, but suggested that favorable social comparisons may influence their well-being in addition to the emotional support.43 Although that study has not examined foreign immigrants, this could explain another reason for the importance of transnational ties.

This study had several limitations. First, foreign workers who came to Korea under the employment permit system had to return to their home country once their contract was over. Therefore, it only included a particular type of foreign worker and not others, so it was not representative of foreign workers as a whole. Second, because of the nature of the employment permit system, most of the participants in the study were young men (less than 5% of the participants were 40 years old and older). Thus, we were not able to examine the effects of different age groups or gender. There are a wide range of age groups and many female immigrants in Korea. Third, we have not examined the generational difference in our study. Given that the effect of transnational social ties as a coping mechanism was found only among second-generation immigrants and not among first-generation immigrants,41 future studies should look into the effect of transnational social ties on health by immigrant generations.

More suggestions on future studies include to examine whether this framework is applicable to other immigrant groups in Korea, such as international marriage female immigrants and North Korean refugees, and examine whether there is a positive association with transnational ties. Moreover, similar to Arat and Bilgili,41 it would be interesting to examine the effect of social ties of the home and host countries in the future to see whether there is a difference in their function as social support. Additionally, since we have not examined the local social support, it would be interesting to examine the effect of local social support and compare between local and transnational social support. Lastly, future studies could expand SRH to other dimensions of health, such as oral health with qualitative research methods to grasp foreign workers’ more detailed perceptions and experiences of discrimination, transnational ties, and their health status.

This study contributes to the existing literature on immigrant and minority health, as well as transnationalism, by examining whether social transnational ties, specifically broad and narrow types, with the home country moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and SRH. The strength of this study is that it is a pioneering study examining the effect of transnational ties on perceived discrimination and SRH on foreign workers in Korea. Recently, a study examined the effect of discrimination on the mental health of immigrants,38 but to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine perceived discrimination and SRH.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study contributes to the literature on the health equity of foreign workers in Korea, which is an understudied group, and suggests the importance of maintaining transnational ties and social support for their well-being and health. It also proposes practical implications that policymakers should explore to help immigrants expand social transnational ties, especially broad transnational ties, whereby social networks in home countries, and even host countries, can be created and maintained. At the same time, the individuals and the society of the host country need to be more aware of accepting and respecting foreigners.

Notes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Song Y, Jang SH.

Data curation: Jang SH.

Formal analysis: Jang SH.

Methodology: Song Y, Jang SH.

Writing - original draft: Song Y, Jang SH.

Writing - review & editing: Song Y, Jang SH.

Abbreviations

SRH

self-rated health

KRW

Korean Won