Association between metabolic syndrome and shift work in chemical plant workers

Article information

Abstract

Background

The study aimed to determine the association between shift work and metabolic syndrome and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the shift and day work groups among workers working in chemical plants.

Methods

Based on medical examination data collected in February 2019, 3,794 workers working at a chemical plant in Korea were selected. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed by adjusting for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), drinking, exercise, smoking, employment period and organic compounds exposure.

Results

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the entire study group was 23.4%, and the prevalence and components of metabolic syndrome in shift worker; waist circumference were higher than those of day workers (84.77 ± 8.64 vs. 83.41 ± 9.42, p < 0.001), systolic blood pressure (129.89 ± 9.47 vs. 127.57 ± 9.47, p < 0.001), diastolic blood pressure (81.22 ± 7.59 vs. 79.34 ± 7.46, p < 0.001), fasting blood glucose (99.27 ± 17.13 vs. 97.87 ± 13.07, p = 0.007), triglycerides (149.70 ± 101.15 vs. 133.55 ± 105.17, p < 0.001), and decreased high-density lipoprotein (53.18 ± 12.82 vs. 55.61 ± 14.17, p < 0.001). As a result of logistic regression analysis on the risk of metabolic syndrome, even after adjusting for age, sex BMI, drinking, smoking, exercise, employment period, organic compound exposure. the odds ratio (OR) for the shift group was 1.300 for daytime workers (Model 1, OR: 1.491; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.273–1.747; Model 2, OR: 1.260; 95% CI: 1.070–1.483; Model 3, OR: 1.309, 95% CI: 1.081–1.585; Model 4, OR: 1.300; 95% CI: 1.063–1.591).

Conclusions

Shift work in chemical plant workers increased the risk of metabolic syndrome, even after adjusting for general factors. To analyze the occupational cause and risk control, it is necessary to analyze the hazardous substances the workers were exposed to and their working environment. Additionally, a large-scale prospective analysis including general factors not analyzed in this study, such as eating habits, is required.

BACKGROUND

According to the International Labor Organization, ‘shiftwork’ means “A method of organization of working time in which workers succeed one another at the workplace so that the establishment can operate longer than the hours of work of individual workers,” whereas ‘nightshift’ means “All work which is performed during a period of not less than seven consecutive hours, including the interval from midnight to 5:00”.1 Shift work is a form of work closely related to nightwork, introduced with the start of modernization to work at night for continuity and efficiency. The definition varies slightly from country to country, but in Korea, ‘night work’ is defined as “working between 22:00 and 06:00”.2 In contrast, the European Council Directive defines ‘night workers’ as “any worker, who, during night time, works at least three hours of his daily working time as a normal course”.3

The most commonly used shift schedules include two or three shifts, irregular shifts (on-call), or continuous night shifts (night-only parts). Hundreds of other cases can occur in shifts depending on whether or not a fixed time is followed, the speed of shifts (2–21 days), the direction of shifts (clock or anti-clock), and the number of breaks.45 The effects of shift work on workers have been studied for a long time. Shift work disrupts the function of regulating biological rhythms in the body, harmfully resulting in changes in hormone concentrations, such as cortisol and melatonin; cardiovascular functions, such as heart rate and blood pressure; secretion of digestive enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract; electrolyte balance; white blood cell count; sleep and wakefulness; as well as cause psychosocial problems and decreases in work efficiency.678 This health impact has been shown to increase the risk of circulatory mechanical diseases such as stroke and coronary artery disease, metabolic chronic diseases like high blood pressure, diabetes and dyslipidemia, gastrointestinal diseases, sleep disorders, and depression, which was also reported by a meta-analysis.9 In addition, shift work was evaluated by IARC in 2007 as a Group 2A with limited human evidence,10 and special health examinations of the cardiovascular, nervous, and gastrointestinal systems have been conducted since 2014 for night workers.

According to the results of the 5th working environment survey in 2017, the proportion of shift workers in Korea was 4,870, accounting for 9.7%, with the proportion continuing to increase to 778 people (7.8%) in the 1st, 774 people (7.7%) in the 2nd, 3,540 people (7.1%) in the 3rd, and 4,199 people (8.5%) in the 4th fourth survey.11 Of these, 24.4% had weekday split shifts (at least 4 hours), 24.4% had permanent shifts (no schedule changes), and 47.7% had shift/circular shifts (if time zones were changeable).12 Metabolic syndrome is defined as a collection of risk factors that can directly promote the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). These risk factors include central obesity, dyslipidemia (high levels of triglyceride [TG] and low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol, low concentrations of high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol), high blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. Some associations, such as the World Health Organization, International Diabetes Federation have proposed various diagnostic standards for metabolic syndrome.13 The currently approved and most commonly used diagnostic criteria in clinical practice and research are proposed in the ATP III of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP-ATP III).14 Various inflammatory agents and cytokines that cause proinflammatory and prothrombotic states are associated with metabolic syndrome.15

Metabolic syndrome, a risk factor for CVD, is steadily increasing worldwide, and according to the analysis of the prevalence of metabolic syndrome over the age of 19 years in Korea using the National Health and Nutrition Survey's 4th to 7th (2007 to 2018), the overall prevalence rate has increased over the past 12 years from 21.6% in 2007 to 22.9% in 2018. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome has increased in all age groups except for those aged 50-59, and it is particularly noteworthy that the prevalence among young men is significantly increasing. The prevalence in those aged 19–29 increased sharply from 6.6% in 2007 to 8.4% in 2018, from 19% to 24.7% in those aged 30-39, and from 25.2% to 36.9% in those aged 40-49.16 A recent multinational meta-research also reported a significant increase in the risk of cerebral CVD over time if people suffer from metabolic syndrome from a young age.17

The proportion of people working shifts was 31.8% of those aged 15–19, and 15.6% of those aged 20–29. according to the results of the 5th working environment survey, thus showing a high proportion among the younger generation.11 Considering that metabolic syndrome increases due to the high rate of shift work among young people, additional research on this particular age group is needed.

Previous studies have examined the relationship between shift work, metabolic syndrome, and the factors that make up metabolic syndrome. The use of extensive data in the Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey (KNHANS) is a representative study, but there are only a few papers on the relationship between shift work and metabolic syndrome in individual industries,18 with none of them involving research in chemical plants. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between metabolic syndrome and shift work in a chemical plant.

METHODS

Study population

This study had a cross-sectional design. Participants were 20 to 62 years old, and were chosen based on regular workers' health checkups, which are regularly conducted every year upon agreement by the workers at a chemical factory in Korea. Medical examinations were conducted at a university hospital in Korea. The examination period was from February 11, 2019, to February 28, 2019. During this period, a total of 3,794 people were examined, of which eight were excluded from the study. This was because only blood tests or physical examinations were performed, which could not analyze parameters used to detect metabolic syndrome.

Data collection and measures

Characteristics included sex, age, body mass index (BMI), employment period, exposure to organic compounds, smoking, drinking, and physical activity. Age was classified as 20 or older to 29 years old, 30 or older to 39, 40 or older to 49 years old, 50 or 59 years old, and 60 years old. Smoking status was classified as smoking now, smoking in the past, and non-smoking, while drinking status was classified as non-drinking, drinking more than once a week, and other drinking groups. Physical activity was defined as aerobic activity, classified as practice when the physical activity of medium strength was practiced for more than 2 hours and 30 minutes per week, high strength physical activity for more than 1 hour and 15 minutes, or by mixing medium strength and high strength physical activity (1 minute high strength is 2 minutes in medium strength). If the physical activity of medium strength was not practiced for more than 2 hours and 30 minutes per week, nor by high strength physical activity for more than 1 hour and 15 minutes and by mixing medium strength and high strength physical activity for more than 1 hour and 15 minutes (1 minute high strength is 2 minutes in medium strength), the physical activity was classified as not practiced. The employment period was as the number of working months from the start day of work to the date of examination. The employment period was measured as the number of working months from the date of starting work to the date of examination. Exposure to organic compounds was defined as the exposed group and the non-exposed group in the ‘108 types of target organic compounds’ of special health checkup which information is provided by company.

Shift work status

In the case of shift work, people who work at night were first classified in the checkup items for each worker provided by the company. Then, shift work was checked through questionnaires and work schedules. Shift workers for at least one month and worked in three groups and three shifts. The timetable followed was 06:00–14:00 in the morning, 14:00–22:00 during the day, and 22:00–06:00 at night.

Metabolic syndrome diagnostic criteria

NCEP-ATP III was used to diagnose metabolic syndrome. A waist circumference (WC) of 90 cm or more for men and 85 cm for women was applied according to the Korean Society for Obesity Standards.19 Diagnosis items included blood pressure (130/85 mmHg or higher), TGs (150 mg/dL or higher), abdominal obesity (90 cm or higher for men, 85 cm or higher for women), HDL cholesterol (less than 40 mg/dL for men, less than 50 mg/dL for women), and fasting blood glucose (110 mg/dL or more). Metabolic syndrome was diagnosed if it satisfied three or more of the 5 parameters mentioned above.

Statistical analyses

To obtain basic statistical data, a frequency analysis was conducted to analyze the general characteristics and healthy lifestyle of the subjects, while descriptive statistics were used to analyze the subjects' health-related indicators.

Differences in average age, blood pressure, WC, and BMI of the subjects were tested using a Student's t-test. An χ2 test was conducted to compare the prevalence of metabolic syndrome by factors based on general characteristics and health lifestyle levels. The group was divided according to shift status, and χ2 was conducted.

A simple logistic regression was performed for each factor to test the risk of metabolic syndrome according to the general characteristics of the subjects, as well as their health lifestyle-related characteristics. Multi-logistic regression was performed to determine the relationship between the two using alternating shifts as independent variables and metabolic syndrome as the dependent variable.

In the unadjusted model (Model 1), a simple logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the association between shift work and metabolic syndrome. In the second model, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed by adjusting for employment period, exposure to organic compounds. In the third model, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed by adjusting for age, sex, BMI, exercise, drinking and smoking. Finally, the 4th model, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed by adjusting for all the aforementioned variables.

The significance level was set to 0.05, and data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical program. (version 25.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics statement

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) review of Soonchunhyang University Hospital, Cheonan. (IRB No. 2021-06-037).

RESULT

Characteristics and lifestyles of study subjects

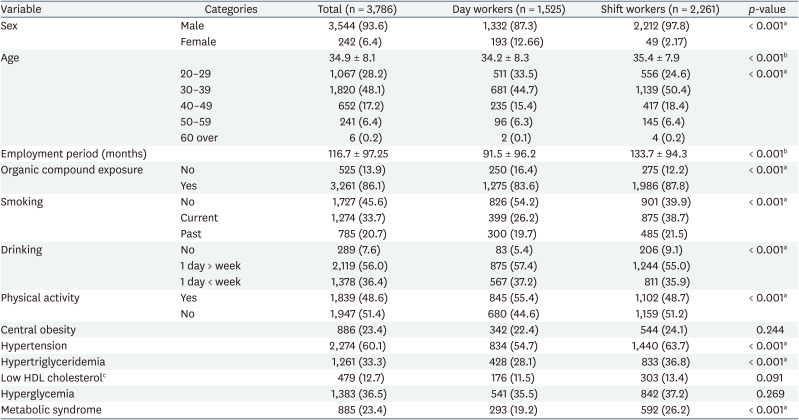

Table 1 shows the results of the characteristics of the study subjects. By sex, males accounted for the majority of subjects at 3,544 (93.61%). The average age was 34.87 ± 8.06 years, with ‘under 30–40 years’ of age having the most with 1,820 people (48.1%), followed by 'under 30' with 1,067 people (28.2%), ‘under 40–50’ with 652 people (17.2%), ‘under 50–60 years of age’ with 241 people (6.4%), and 6 people (0.2%) over 60 years of age. The employment period was 91.5 ± 96.2 months in the daytime group and 113.7±94.3 months in the shift working group. Exposure to organic compounds was 1,275 (83.6%) in the daytime group and 1,986 (87.8%) in the shift group. Regarding smoking status, 1,274 had a ‘current smoking’ status (33.65%), 1,727 people a ‘non-smoking’ status (45.62%), 785 people a ‘past smoker’ status (20.73%), 186 people a ‘drinking’ status (71.8%) and 73 with ‘nondrinking’ status (28.2%). As for the frequency of drinking, 2,119 people (55.97%) drank ‘more than once a week’, 1,378 people (36.4%) ‘less than once a week’, and 289 people (7.63%) were ‘nondrinking’. The proportion of those who practiced physical activity was 1,839 people (48.57%), and the proportion who did not practice it was 1,947 people (51.43%).

Metabolic syndrome prevalence

Of the 3,786 subjects, 885 (23.4%) had metabolic syndrome. As shown in Table 2, the positive rates for metabolic syndrome were high blood pressure (60.1%), high blood sugar (36.5%), high TGs (36.5%), abdominal obesity (23.4%), and HDL cholesterol (12.7%), respectively.

Difference between physical measurements and laboratory findings of shift worker and day worker

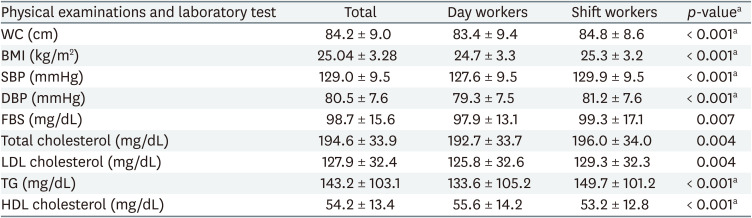

The WCs of the day and shift groups were 83.41 ± 9.42 cm and 84.77 ± 8.64 cm, respectively, which were higher in the shift group (p < 0.001). In the case of body mass index, the BMI of the shift work group was 25.27 ± 3.23 kg/m2, which was higher than that of the day worker 24.71 ± 3.32 kg/m2 (p < 0.001).

The systolic blood pressures (SBPs) of the day and shift groups were 127.57 ± 9.47 mmHg and 129.89 ± 9.47, and the diastolic blood pressures (DBPs) were 79.34 ± 7.46 mmHg and 81.22 ± 7.59 mmHg. The SBP and DBP were significantly higher in the shift group (p < 0.001). Fasting blood glucose levels were 97.87 ± 13.07 mg/dL and 99.27 ± 17.13 mg/dL, and the shift group showed significantly higher values (p = 0.007).

Total cholesterol was 192.67 ± 33.71 mg/dL and 195.95 ± 33.95 mg/dL, and LDL cholesterol was 125.79 ± 32.60 mg/dL and 129.28 ± 32.25 mg/dL in the day and shift groups, respectively, which was significantly higher in the shift group (p = 0.004). TG levels were significantly different in the day and shift groups, which were 133.55 ± 105.17 mg/dL and 149.70 ± 101.15 mg/dL, respectively. The values were higher in the shift group (p < 0.001). Finally, HDL cholesterol levels were significantly lower in the shift group at 55.61 ± 14.17 mg/dL and 53.18 ± 12.82 mg/dL in the day and shift groups, respectively (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

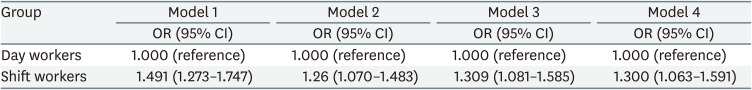

Effect of shift work on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome

To analyze the effect of shift work on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, simple logistic regression analysis was performed without considering any other factors in Model 1 (Table 3), and the risk of metabolic syndrome was approximately 49% higher in the shift work group than in the nonshift work group (odds ratio [OR]: 1.491; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.273–1.747). In Model 2, which was the result of adjusting for employment period and exposure to organic compounds, the risk of metabolic syndrome was approximately 26% higher in the shift work group than in the non-shift work group (OR: 1.260; 95% CI: 1.070–1.483). Even in Model 3, which was adjusted using variables of age, sex, BMI, drinking smoking, exercise status, the risk of metabolic syndrome was 30.9% higher in the shift work group than in the non-shift work group (OR: 1.309; 95% CI: 1.081–1.585). In Model 4, in which all variables were added, the shift group increased about 30% compared to the non-shift group (OR: 1.300; 95% CI: 1.063–1.591).

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the NCEP-ATP III standards for metabolic syndrome to examine the association between shift work and metabolic syndrome. According to this study, the risk of metabolic syndrome from shift work increased by 30%, even after adjusting for general characteristics such as age, sex, BMI, organic compounds exposure, employment period, drinking and smoking status (OR: 1.300). According to a previous study, the OR of metabolic syndrome caused by shift work was 6.3 in a study of 254 female workers at a dyeing plant in Daegu in 2013.20 In a study of 1,732 male steel workers in 2017, the odds ratio was 2.26,21 which was higher than in this study.

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the study group was 23%, whereas it was 22.9% in the 4th to 7th KNHANS. There was a 24.7% prevalence rate in those aged 30–39 years old, which was similar to that of the study.22 Considering the effects of health workers, the prevalence rate of the study seemed relatively high.

In a preliminary study on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in certain occupations in Korea, the prevalence rate of electronic products manufacturing male workers in 2006 was 10.5,23 and in 2009, the prevalence rate of male workers in shipyards was 15.0%,24 which meant that the prevalence was lower than in this study. The prevalence rate of research on shift guards in 2019 was 29.8%,25 which did not show much of a difference considering that the average age of the subjects was 34.9 years.

Metabolic syndrome is known to be affected by general factors, such as age, sex, weight,26 employment period, smoking, drinking, exercise, and diet. In this study, age, sex, BMI, smoking, and exercise were significant influencing factors.

In this study, it was impossible to analyze the subjects' dietary habits and nutrition, because the analysis was conducted based on the results of special health examinations. Previous studies have shown a significant relationship between eating habits and metabolic syndrome.27 At workplaces where researchers work, food service companies with more than 10,000 employees who can be classified as large corporations provide meals with professional nutritionists. Usually, fundamental problems with shift workers' eating habits include eating time and pattern problems, unhealthy food, and high calorie intake.2829 Previous studies found that as manufacturing day workers use the cafeteria for eating only one meal at lunch, whereas shift workers usually eat two meals at night, were not much different for eating habit.30 However, while diet time and pattern problems have not been solved, nutritional problems such as high calories are expected to be relatively small. However, accurate data were not available because the exact type of meal, amount, frequency, and calories were not investigated.

No previous research on metabolic syndrome in chemical workers in Korea was found. In the case of foreign studies, a Germany study reported a prevalence of 23.5% in 2008,31 and 30.2% in Italy in 2011.32 As a study in a similar field, in Korea in 2016, a study on the relationship between shift work and coronary computed tomography angiography in chemical factory workers showed that, unlike this study, shift worker and day worker were statistically no difference in BMI, lipid, and blood glucose, smoking and drinking. Nevertheless, the odds ratio of coronary artery calcification was 2.89.33

In the case of chemical plants, the types of organic compounds used are very diverse, and substances such as persistent organic pollutants such as dioxin and persistent organic pesticides in the environment are known to increase the risk of metabolic syndrome by affecting insulin resistance and lipid metabolism. In a recent study, some perfluoroalkyl substances, such as perfluorononanoic acid, have been reported to increase the risk of metabolic syndrome.34 There is also a study from the Korea that increases the risk of some metabolic syndrome diagnostic index items (blood pressure, cholesterols, blood glucose) due to changes in the physiological concentration of epinephrine and norepinephrine in workers exposed to monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as stylene, toluene, which are often seen during special health examinations in chemical plants.35 The chemical plant, the subject of this study, is a company that manufactures storage batteries and their materials, such as cathode materials, polarizers and optical materials, as well as high-performance materials using various types of chemicals (N,N-dimethylformamide, methylethylketone, cyclohexane, etc.). The odds ratio for exposure to organic compounds was significant before the general factors are adjusted, but was not significant after the general factor are adjusted, which was different from the results of previous studies. And the prevalence of hypertension among the metabolic syndrome components of this study was particularly high (60.2%), and think it might have something to do with this.

The chemical plant, which was the subject of this study, used three groups of three shifts. Previous studies reported that the adverse health effects of two-shift work (12-hour work) were higher than those of three-shift work (8-hour work),36 and the adverse health effects of counterclockwise shift work patterns were higher than those of clockwise shift work.37 This may be the reason for the low risk compared with other studies.

The limitations of this study are as follows: First, since it was a cross-sectional study, the causal relationship could not be revealed. Further prospective studies on large-scale personnel in the field of chemistry are needed. Second, more specific data could not be obtained because we had no choice but to rely only on related results, health practices, and special health examination results and questionnaires. For this reason, it was not possible to separate and analyze only the shift work period during the employment period, and the increase in shift work period, which was significant in previous studies,38 may have been shown to be insignificant in this study. Third, quantitative analyses and detailed classification of exposure to hazardous chemicals were insufficient. This requires additional research through the analysis of biological exposure indicator and other exposure data provided by the company in the future. Fourth, data collection such as shift work patterns (clockwise, counterclockwise, etc.) and overtime hours were insufficient, so analysis was not possible.

Nevertheless, the significance of this study is that it is the first study on the relationship between shift work and metabolic syndrome among chemical workers in Korea. This could be the first step in further research on the risk of metabolic syndrome in chemical factory workers. Second, it has representativeness and reliability of a group, because it is a data survey on a relatively large population group of 3,786 people in a single workplace.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, shift work in chemical plant workers increased the risk of metabolic syndrome, even after correcting for general factors. To analyze the occupational cause and risk control, analysis of detailed hazardous substances and working environment is needed. In addition, a large-scale, forward-looking additional analysis is needed, including general factors that could not be analyzed in this study, such as eating habits. The development of primary prevention programs, including possible shift directions and time improvements, could help reduce the risk of CVDs for night shift workers at chemical plants, as well as secondary precautions for people with metabolic syndrome categories.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Notes

Funding: This research was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Chai SR.

Data curation: Chai SR, Lee SY, Lee YJ, Jang EC, Kwon SC, Min YS.

Formal analysis: Chai SR, Lee SY, Lee YJ, Jang EC, Kwon SC, Min YS.

Investigation: Chai SR, Lee SY.

Writing - original draft: Chai SR.

Writing - review & editing: Kwon SC.

Abbreviations

NCEP-ATP III

ATP III of the National Cholesterol Education Program

BMI

body mass index

CI

confidence interval

CVD

cardiovascular disease

DBP

diastolic blood pressure

FBS

fasting blood sugar

HDL

high-density lipoprotein

KNHANS

Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey

LDL

low-density lipoprotein

OR

odds ratio

SBP

systolic blood pressure

TG

triglyceride

WC

waist circumference