A descriptive study of claims for occupational mental disorder: adjustment disorder

Article information

Abstract

Background

The number of claims of Industrial Accidents Compensation Insurance (IACI) for mental illness has increased. In particular, the approval rate was higher in cases with confirmed incident circumstances such as adjustment disorder, acute stress disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. With increased numbers of filed IACI applications and their approval rates, the need to evaluate various work-related incidents and stressors consistently is also increasing.

Method

In January 2015–December 2017, among the cases of industrial accidents filed for mental illness and suicide by the Korea Workers' Compensation and Welfare Service, 76 filed or approved adjustment disorder cases were included. The cases of adjustment disorder were applied in this study to the “Criteria for Recognition of Mental Disorders by Psychological Loads” established in Japan in 2011 and investigated if cases were approved/rejected consistently. Additionally, features with the greatest influence on approval/rejection were examined quantitatively.

Results

The number of applications more than doubled from 2015 to 2017, with the approval rate rising from 66.7% to 90.6%. Among the major categories, applications of adjustment disorder related to “interpersonal relationships” were the largest number of applications. Applications related to “sexual harassment”, “interpersonal relationships”, and “accidents and experiences including fires” showed relatively higher approval rate. The approval rate was the lowest in the case of “change in the amount and quality of work”.

Conclusions

Approved cases tend to have special precedents and strong intensity. The main reasons for the rejection were that there were no special precedents and that the intensity of the case was weak. These 2 were the most important factors in determining approval/rejection.

BACKGROUND

Mental illness in the workplace is regarded as a significant problem worldwide. The United Kingdom Department of Health and the Confederation of British Industry estimates that 15%–30% of the workforce may have mental problems in some form. The European Mental Health Agenda of the European Union also identified the prevalence of mental illness problems at work, revealing that about 20% of the adult working population has mental health problems. In the United States, it is estimated that > 40 million people have mental health problems, of whom 4–5 million suffer from severe mental illness [1]. Furthermore, studies have shown that there is a high prevalence of mental illness among the working population in the United States. According to a study of 60,556 people, 4.5% presented with severe diagnosable mental problems and 9.6% had moderate mental problems with signs of mental illness [2].

The prevalence of mental illness is also increasing in South Korea. According to the 2016 Mental Illness Survey, the lifetime prevalence of mental illness was 25.4% and one of every 4 people experienced mental illness at least once in their lifetime. The prevalence of mental illness per year indicated 12.2% in males and 11.5% in females [3]. The number of claims of Industrial Accidents Compensation Insurance (IACI) for mental illness has also increased [45]. In particular, the number of IACI applications for mental illness over the past 5 years has increased, indicating 137 in 2014, 165 in 2015, 183 in 2016, 213 in 2017, and 268 in 2018 [6]. Of these, about 57.7% of applications in 2017 were approved and the approval rate for January–August 2018 increased to 75.5%. In particular, the approval rate was higher in cases with confirmed incident circumstances such as adjustment disorder, acute stress disorder (ASD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Therefore, with increased numbers of filed IACI applications and their approval rates, the need to evaluate various work-related incidents and stressors that can cause mental illness in the workplace such as emotional labor, bullying, sexual harassment, reassignment, and retirement pressure [278] are also increasing.

Currently, “The Legal Issues on the Recognition of Work-related Mental illness,” the guidelines of the Korea Workers' Compensation and Welfare Service (KCOMWEL), require the description of shocking events and major stress experiences over a period of 6 months. Additionally, daily stressors, non-work stressors, and personal characteristics should be described. Furthermore, the classification of mental disorder was divided into suicide, PTSD, and depressive/adjustment/anxiety disorder, among which depressive/adjustment/anxiety disorder is not clearly distinguished.

However, considering the definition and mechanism of occurrence of adjustment disorder, it cannot be classified with depression and anxiety disorder [910111213]. PTSD and ASD are classified separately as trauma- and stress-related disorders in Diagnosing Mental disorder and Statistics. Adaptation disorder refers to where emotional or behavioral symptoms develop within 3 months of being exposed to recognizable stressor(s) [14]. Therefore, if an investigation is conducted without considering the differences between mental illnesses, the consistency of judgments cannot be secured.

Given this fact, when assessing the work relevance of adjustment disorder, it is essential to state the existence of obvious “Event (stress)” influenced by significant damage in social, work-related, or other important areas during the adaption period. Furthermore, it is important to investigate whether “Event (stress)” originates from work. However, not only the existence of the work-related event (stress) but also the severity of event (stress) and personal characteristics should be considered [15].

Understanding the severity of an event (stress) or personal characteristics requires collecting data consistently. To achieve consistency in information collected during an investigation, the investigation methods in Japan include specific features that may affect the development of mental disorder that are embodied and categorized in the guidelines. Therefore, the cases of adjustment disorder in South Korea were applied in this study to the “Criteria for Recognition of Mental Disorders by Psychological Loads [16]” established in Japan in 2011 and investigated if cases were approved/rejected consistently. Additionally, features with the greatest influence on approval/rejection were examined quantitatively.

METHODS

Subjects

In January 2015–December 2017, among the cases of industrial accidents filed for mental illness and suicide by the KCOMWEL, 76 filed or approved adjustment disorder cases were included.

Qualitative analysis

Data containing various evidence types of work-related features or personal events from IACI cases were provided including: working conditions; various job stressors; interviews with workers, subscribers, coworkers, and employers; diagnoses; medical records; suicide notes; diaries; cellphone messages; official investigation results; and decision statements from the Committee on Occupational Disease Judgement.

For the classification of the applications, 1 medical resident and 2 experts in occupational and environmental medicine prepared a form that included the categories and specific types of events (stress). It also included basic personal data presented by the Criteria for Recognition of Mental Disorders by Psychological Loads established in Japan after reviewing 76 claimed cases. The information obtained in the form included occupational accidents, individual characteristics, personal incidents, and approval/rejection of the events.

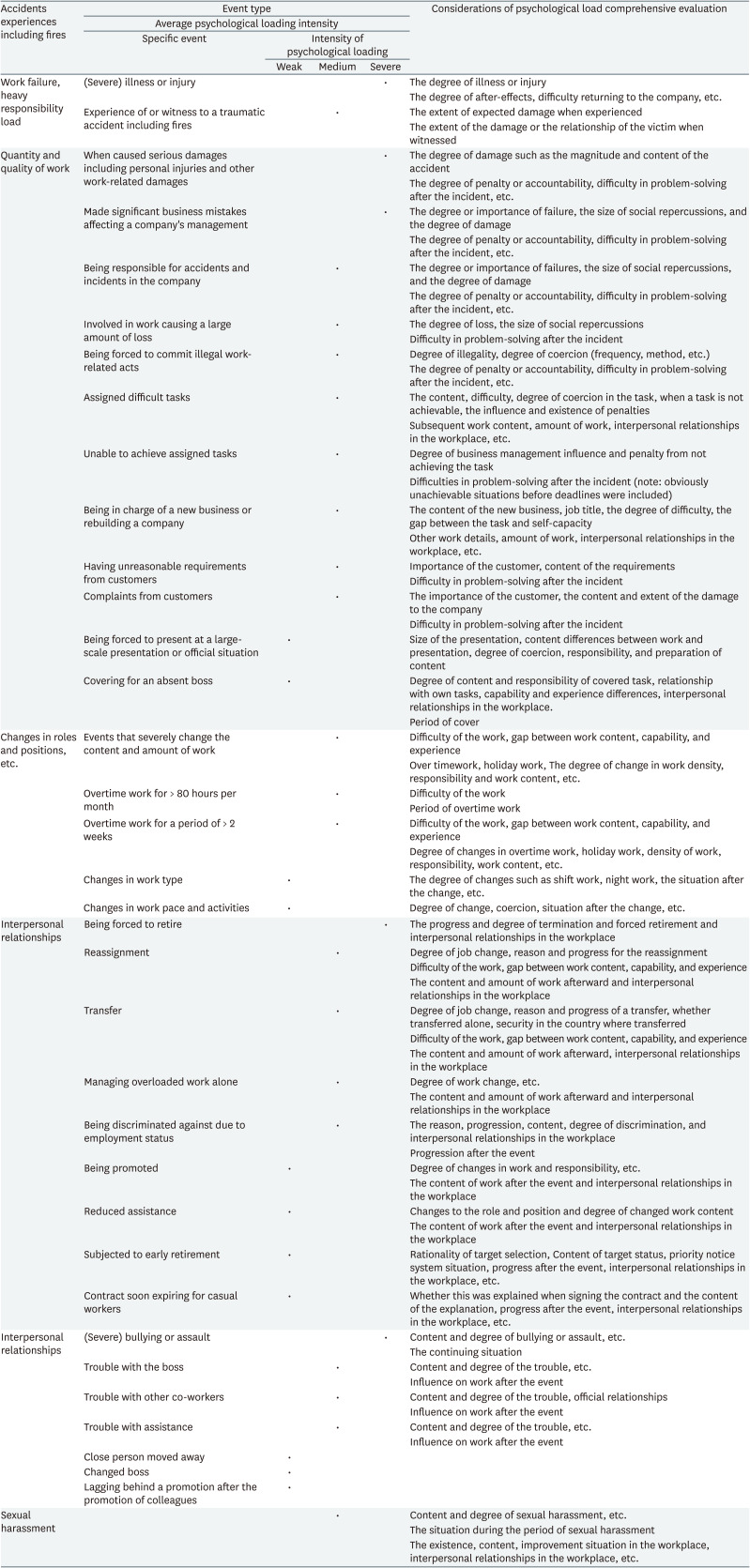

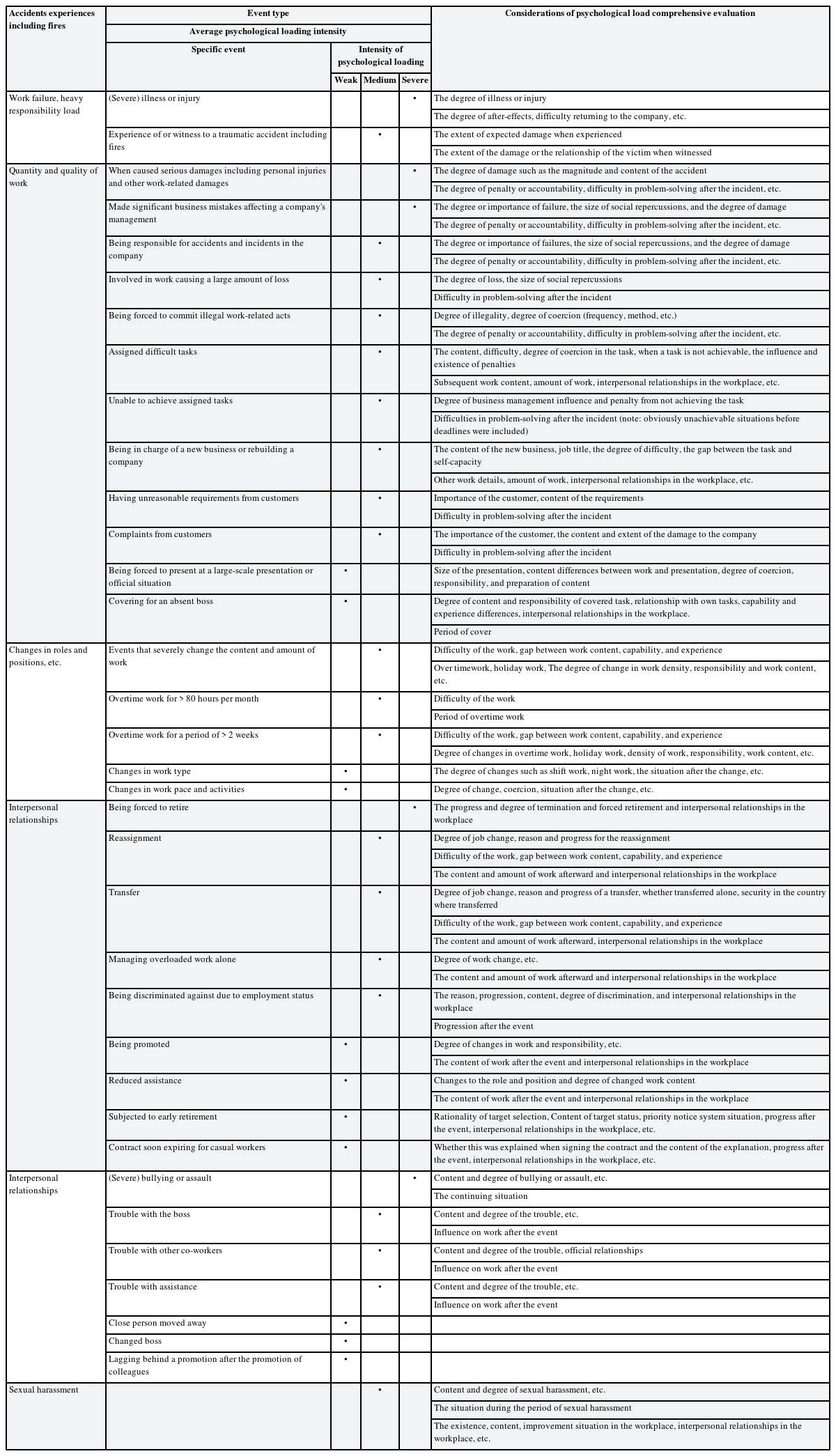

As the investigation manual of KCOMWEL refers to Japanese Work-Related Disease Investigation Standards, work-related situations were classified based on the categories and specific types of events (stress) presented in the Japanese Mental Illness Recognition Standards 2011. The Japanese Mental Illness Recognition Standards 2011 largely divide work related events (stress) into 6 major categories (experience of accidents or fires, work failure and heavy responsibility load, quantity and quality of work, changes in role positions, interpersonal relations, and sexual harassment). Moreover, the major categories include the following specific events (Table 1).

Major/minor categories of work-related events and distinguishing the intensity of psychological loading established in Japan in 2011

The major category of “Accident experiences including fires” contains “(Severe) illness or injury” and “Experiencing or witnessing a traumatic accident including fires.”

“Work failure and heavy responsibility load” includes following events: when serious damages are caused including personal injuries and other work-related damage; significant business mistakes that affect a company's management; being responsible for accidents and incidents in a company; involved in work causing a large amount of loss; being forced to commit illegal work-related acts; assigned difficult tasks; unable to achieve assigned task; being in charge of a new business or rebuilding a company; having unreasonable requirements from customers; having complaints from customers; being forced to present at a large-scale presentation or official situation; covering for an absent boss.

“The quantity and quality of work” includes “Events that severely change the content and amount of work,” “Changes in pace, activity, and work types,” “Having overtime work for > 80 hours per month,” and “Overtime work for a period of > 2 weeks.”

The major category of “Changes of roles and positions” includes “Being forced to retire,” “Reassignment,” “Transfer,” “Managing overloaded work alone,” “Being discriminated against due to employment status,” “Being promoted,” “Reduced assistance,” “Subjected to early retirement,” “Contract soon expiring for casual workers.”

The major category of “Interpersonal relations” includes “(Severe) bullying or assault,” “Troubles with the boss,” “Troubles with other co-workers,” and “Troubles with assistance,” “Close person moved away,” “Changed boss,” “Lagging behind a promotion after the promotion of colleagues.”

Lastly, sexual harassment includes sexual assault and sexual violence.

This work was carried out over one month from May to June 2018. After that, a cross-check among study investigators was conducted on the data entered. Discrepancies on primary classifications were reclassified through discussion. There were 2 discussions.

The quantitative analysis for the incidence of adjustment disorder and the intensity of the event was performed after the work and events related to the incidence of the disorder was identified and entered. The Japanese Mental Illness Recognition Standards represented “Average psychological loading intensity (weak, medium, severe)” for each specific situation. For example, average psychological loading intensity is classified as “Severe” for (heavy) diseases, injury from an accident, or fire in a major category. A miserable accident, a fire, or witness to the event is classified as “Medium.” We also followed this classification. However, the psychological loading intensity was controlled according to the “Considerations of psychological load comprehensive evaluation,” after reviewing each case of industrial accidents. For example, the psychological loading intensity was changed to “Severe” in a miserable accident or fire or witness where the victim witnessed a nearby coworker's death. The psychological loading intensity was also determined by cross-checking with each other. The 3 authors subsequently discussed the primary classification to reach an agreement.

Factors identified for evaluating individual characteristics were as follows: age, sex, history, past mental disorders recorded in the medical record. History of alcohol abuse, personality/tendency, and social problems related to social adaptation were identified through data from industrial accident compensation insurance. It was necessary to secure objectivity due to the subjective characteristics of data such as statements by the victims, coworkers, and employers with regard to the history of alcohol abuse, personality/tendency, and adaptation to social problems. Therefore, alcohol abuse was determined according to statements such as “Drinking frequently,” “Absence or tardiness due to alcohol,” or “Problems with coworkers due to alcohol” in statements made by the victims, coworkers, and employers, or “Alcohol dependent/dependency,” “Alcohol abuse,” “Alcohol problem,” “Chronic alcoholics,” “Heavy drinking,” and “Frequent drinking” documented in the medical records. Abnormality of personality/tendency was determined according to statements such as “Aggressive or violent personality,” “Excessively passive personality,” “Anti-social personality,” “Dependent personality,” “Usually rough-spoken,” or “Self-centered personality.” Similarly, the social problem was determined based on statements such as “Not hanging out with coworkers,” “Not adapting to work-life (before/at first),” or “Not adapting to tasks.”

Additional personal evaluation features from the Japanese Criteria of Mental Illness Recognition Standards are utilized to assess personal factors.

Personal events include divorce or separation of couples, severe illness or injury including miscarriage, trouble with partner, pregnancy, and retirement.

The events involving family or relatives include death of spouse, child, parent, or sibling, severe illness or injuries to a spouse or child, having a relative in a very difficult situation, negative relationships with relatives, suffering, severe illness or injury to parents, engaged family member or when engagement plans become concrete, child entering school or has important exams, trouble with children, disobedience or troublesome behavior from children, increased (childbirth) or decreased (children leaving home to be independent) family members, and spouse starting a new job or becoming jobless.

In monetary relations events, there were situations with losing a large amount of money or increased expenditure, increased income, difficulty in debt repayment over time, and having housing or consumer loans.

Events and experiences of accidents which are not related to work cover natural disasters including fires, involvement in crime, theft at home, traffic accidents, and light violations of the law.

Events of changes in the residential environment include deteriorating environment around the house (including personal surroundings) such as loud noises, purchasing a house or land, or having established a purchasing plan, living with people other than family members (such as acquaintances or tenants).

Interpersonal relationships other than the workplace include situations of being cut-off from friends, death of close friends, being broken-hearted, troubles with romantic partner, and troubles with neighbors.

Quantitative analysis

With 76 cases classified, we analyzed the frequencies of the descriptive characteristics.

Ethics statement

All ethical requirements for this study have been met. The study protocol was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of Wonjin Institution for Occupational and Environmental Health.

RESULTS

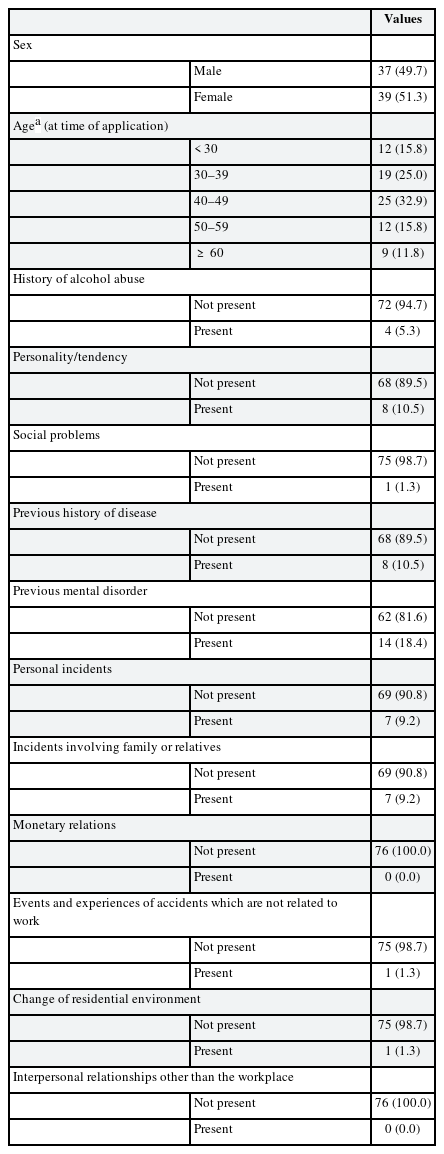

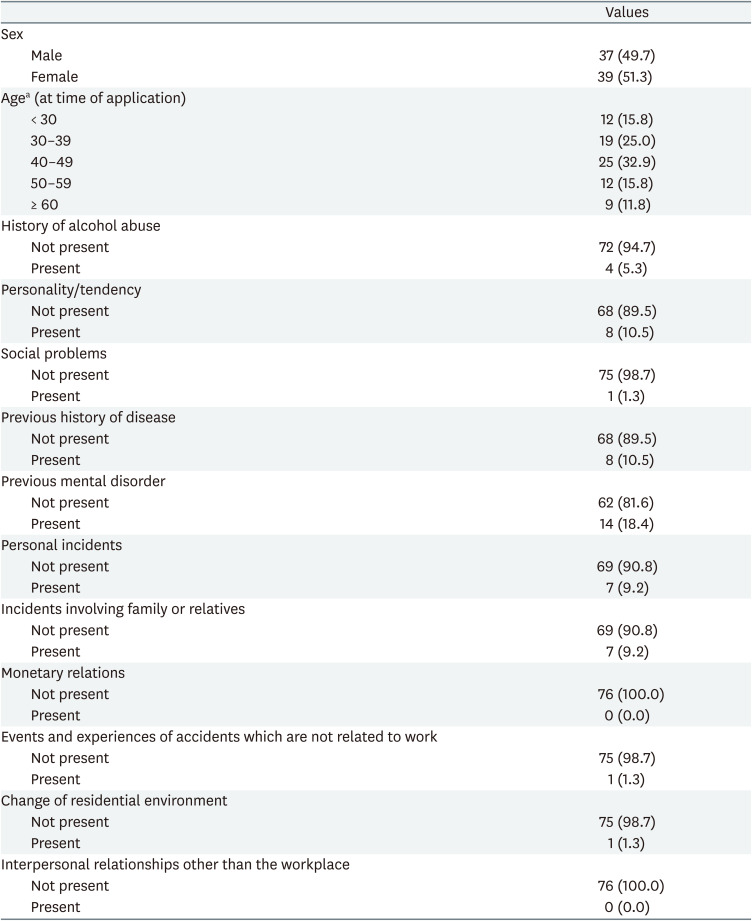

In Table 2, when considering the sex configuration of the 76 cases filed in 2015–2017, 37 (48.7%) were male and 39 (51.3%) were female. Furthermore, it was observed that applicants in 12 cases younger than 30 years (15.8%), 19 cases were in their 30s (25.0%), 25 cases were in their 40s (32.9%), 12 cases were in their 50s (15.8%), and nine cases were in their 60s or older (11.8%).

It was indicated that the applicants were not significantly related to alcohol abuse, indicating 72 non-alcohol-related cases (94.7%) out of 76 cases, showing only 4 cases (5.3%) being related to heavy drinking history. Moreover, out of the 76 cases, personality/trend problems were identified in 8 cases (10.5%) while social adaptation problems were present in only one case (1.3%). Furthermore, 14 cases (18.4%) were related to previous mental disorder.

Besides, among personal events and accidents that can influence the diagnosis of adjustment disorder, personal events, and events involving family and relatives each had 7 cases (9.2%). No cases were related to monetary problems or interpersonal relationships other than the workplace, and one case (1.3%) each was related to events and experiences of accidents which are not related to work and changes of residential environment (Table 3).

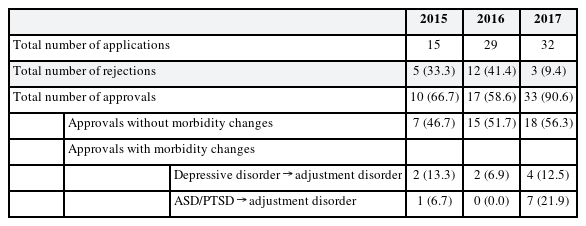

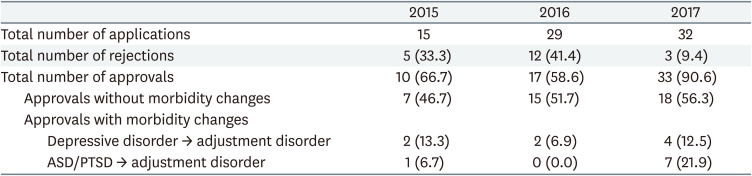

Of the 76 applications in 2015–2017, 56 were approved (73.7%) and 20 were rejected (26.3%). The number of filed cases increased each year, indicating 15 cases, 29 cases, and 32 cases in 2015, 2016, and 2017, respectively. Similarly, the approval rate was observed to increase from 66.7% in 2015 to 58.6% in 2016 and then to 90.6% in 2017. The cases approved for change to adjustment disorder in the review process were 3 in 2015, 2 in 2016, and eleven in 2017 (Table 4).

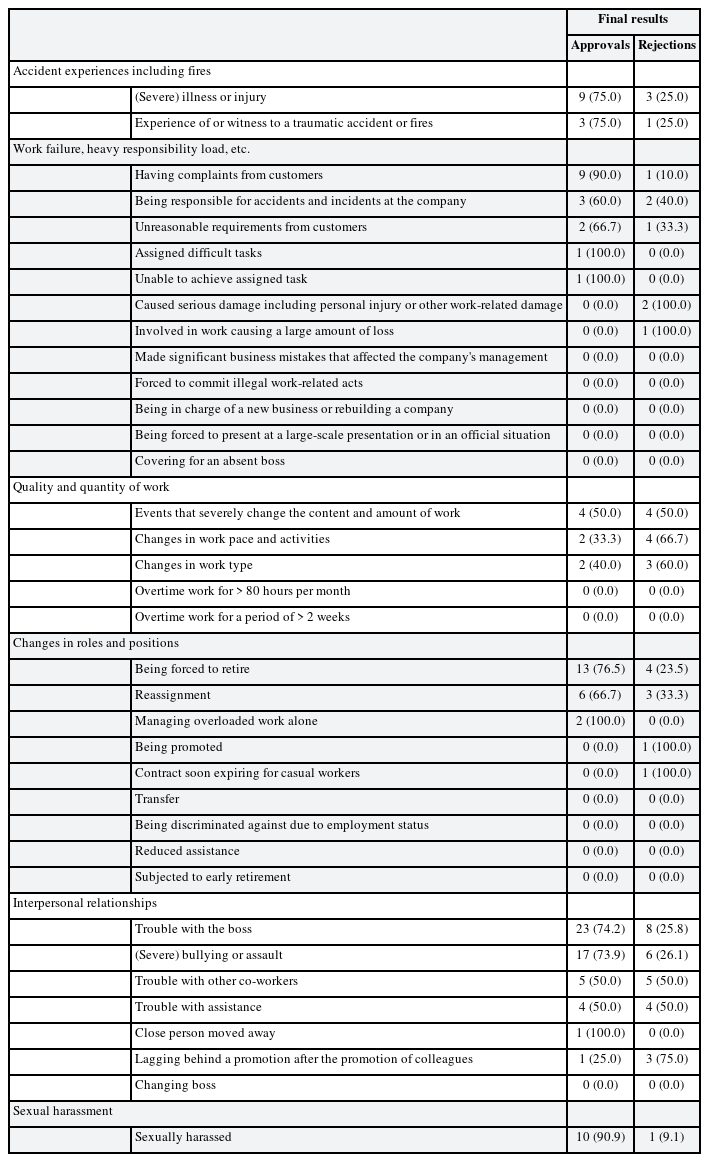

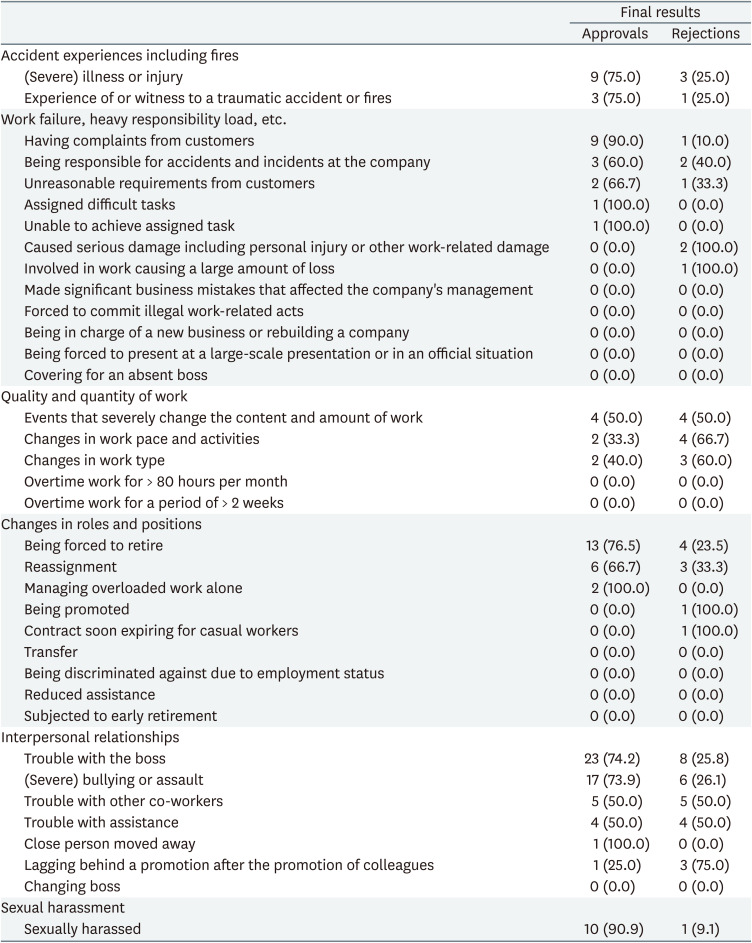

In the major category of “Accidents experiences including fires,” 9 cases were approved and 3 cases were rejected in the events of “Experiencing accidents including fires.” In comparison, there were 3 approved cases and one case was rejected in the events of “Experiencing or witnessing traumatic accidents.”

In the major category of “Work failure, heavy responsibility load,” 9 out of 10 applications were approved in events of “Having complaints from customers.” Furthermore, the events of “Being responsible for accidents and incidents in the company” had 3 approved cases. Two out of three cases were approved with events of “Unreasonably heavy loads of requirements from customers.” Moreover, each of one case was approved with events of “Assigned with difficult tasks” as well as in “Not able to achieve assigned task.” There were 2 rejected cases in the event of “When caused serious damages including personal injuries and other work-related damages,” and one application with the event of “Involved in work causing a large amount of loss was rejected.”

In the major category of “Changes in the quantity and quality of work,” 4 cases were approved out of 8 filed cases with “Events that severely change the content and amount of work.” Furthermore, only 2 cases were approved out of 6 filed cases with “Changes in work pace and activities,” and 2 cases out of 5 cases were approved with “Changes in work type.”

In the Major category reporting “Changes in roles and positions,” of 17 filed cases with “Being forced to retire,” there were 13 approved cases. Furthermore, 6 cases out of nine filed cases were approved with “Reassignment,” while all of 2 cases were approved with “Managing overloaded work alone.” However, each of one case of “Being promoted” and “Contract soon expiring for casual workers” was rejected.

In the “Interpersonal relationships” major classification, “Trouble with the boss” showed the highest number of filed applications, indicating 31 cases, with 23 approved. In the events of “(Severe) bullying or assault,” 17 cases out of 23 cases were approved. Moreover, “Trouble with other co-workers” included 5 approved cases out of 10 filed cases, while “Trouble with assistance” had 4 approved cases out of 8 filed cases. One case filed with “Close person moved away” were approved, and only 1 case was approved out of 4 filed cases with “Lagging behind a promotion after promotion of colleagues.”

In the major category of “Sexual harassment,” 10 cases were approved from 11 filed cases in total (Table 5).

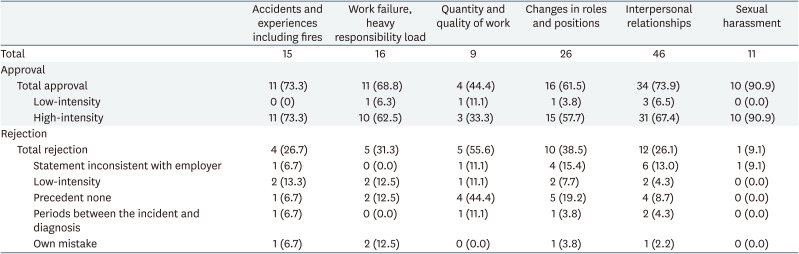

To examine the reasons for approvals and rejections, the intensity of the event in approved cases and the grounds for rejected cases were investigated.

The rejected cases with various reasons were counted as duplicates.

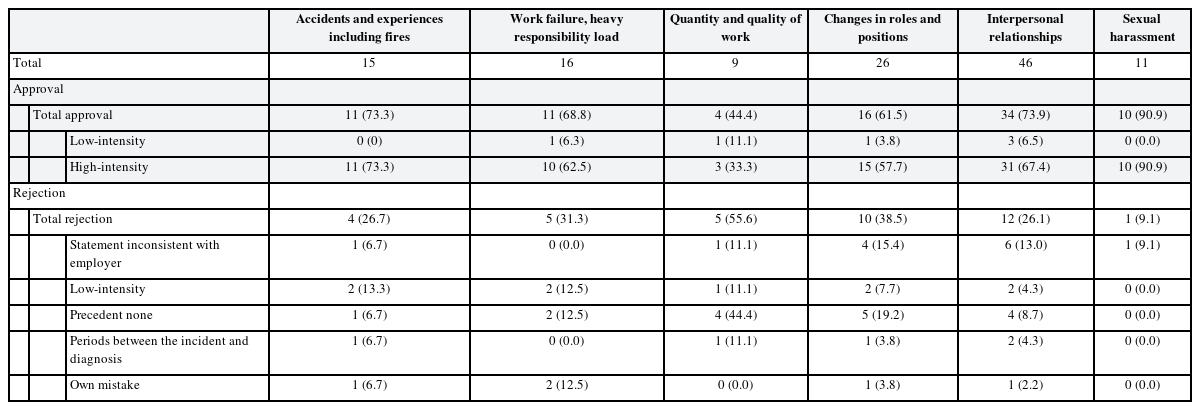

In total, 15 cases of “Experiencing accidents including fires” were filed for adjustment disorder, of which 11 were approved as work-related. In all approved cases, the intensity of the incident was found to be high. Looking at the reasons behind the 4 rejected cases, statements were inconsistent with the employer in one case, there was weak intensity in 2 cases, no precedent in 1 case, a prolonged period between the diagnosis and the event in 1 case, and own mistake in 1 case.

There were 16 filed cases with “Work failure and heavy responsibility,” of which 11 were approved. Only one case of the 11 approved cases was found to have a low intensity and 10 cases had a high intensity. Furthermore, the reasons for the 5 rejected cases were: weak intensity in 2 cases, lack of precedents in 2 cases, and own mistake in 2 cases.

The 9 cases filed with the “Change in the quantity and quality of work,” included 4 approved cases and 5 rejected cases. Three of the four approved cases had a high intensity. Of the 5 rejected cases, it was judged that 4 had no precedents. Furthermore, statements inconsistent with the employer, weak intensity, and a prolonged period between the diagnosis and the event each accounted for one case.

In total, 26 filed cases were related to “Changes in roles and positions.” Among the 16 approved cases, 15 cases were high intensity. Furthermore, of the 10 rejected cases, 4 cases had statements inconsistent with the employer and 5 cases were without precedents. In addition, 2 cases had weak intensity, 1 case had a prolonged period between the diagnosis and the event, and 1 case was evaluated as own mistake.

In total, 46 applications were filed as “Interpersonal relationships,” of which 34 were approved and 12 were rejected. Among the approved cases, 31 had high intensity. Moreover, the most common reason for rejection was statements inconsistent with the employer, accounting for 6 cases out of the 12 rejections. In addition, 4 cases lacked precedents, 2 cases had weak intensity, 2 cases had a prolonged period between the diagnosis and the event, and 1 case was confirmed to have been own mistake.

Lastly, 11 cases of “Sexual harassment” were filed, of which 10 cases were approved and 1 was rejected in which statements were inconsistent with the employer.

DISCUSSION

The mental disorder and suicide standards and investigation guidelines in South Korea have been revised several times. When PTSD was first included in the current accreditation standards in 2013, “Depressive episodes and adjustment disorders resulting from emotional damage caused by violence or verbal abuse from customers and related stress” was included in 2015. Although the scope of the recognized diagnoses has been expanded, it seems that the investigation process and method have not been improved.

This study presumed 2 major points that need to be improved in relation to the recognition of work-related adjustment disorder in South Korea. First, beyond the existence of work-related events (stress), which has been overlooked thus far, the severity of the event (stress) and personal characteristics should be investigated. Second, it was necessary to collect data in a consistent form to understand the severity of the event (stress) or personal characteristics. Since the survey format is not standardized, the efficiency of the necessary information for judgment has deteriorated and the uniformity of the collected information type is not secured. Based on these problems, this study referred to the Japanese Criteria of Work-related Mental disorder Recognition.

The number of claims regarding mental disorder rocketed in Japan from 42 in 1998—just before the guidelines were established in 1999—to 1,181 in 2010. It was pointed out that the review period was too long, taking approximately 8.6 months on average (2010), which increased the administrative burden. Thereby, the Ministry of Health and Welfare through a total of 10 "specialized review boards on standards for recognition of industrial accidents of mental disorders," in October 2010, began to revise the guidelines. The review board prepared a revision of the recognition criteria based on the study of the validation of average psychological loading intensity, which was based on a study of the "Research on the method of stress assessment" [17] conducted in 2010 for 10,000 workers in a wide range of occupational group in the Ministry of Health and Welfare. Thus, events corresponding to the 6 major categories presented in the previous 1999 evaluation guidelines were more specifically presented with the revision of the recognition criteria in 2011 [16], and the evaluation of psychological loading intensity corresponding to each event was also established. After this, one study reported that the investigation process's efficiency and objectivity were secured [18]. Additionally, it was reported that the promptness of the evaluation was secured by omitting the procedure for judgment by psychiatrists and arranging independent cases where the expert judgment was required instead [19].

To apply these precedents, this analysis of adjustment disorder cases examined what features affected the approval and rejection of adjustment disorder by referring to the categories and specific features from Japanese accreditation standards.

The number of applications on adjustment disorder corresponded to 76 cases from 2015 to 2017. The number of applications more than doubled from 2015 to 2017, with the approval rate rising from 66.7% to 90.6%.

The ratio of men and women with adjustment disorders is known to be higher in women at 1:2 [14]. However, the number of applications according to sex in this study was similar (37% and 39%, respectively). This was thought to be because the number of people engaged in economic activities is smaller for women than in men [20]. It is also possible that women's employments are more unstable in Korea, making it difficult to apply for industrial accidents or a tendency for women's psychiatric disorder to be treated as a personal disease. If not for this reason, it is necessary to determine whether there are adjustment disorders diagnosed as non-work factors, which may require data from the industrial accident and follow-up studies based on a large number of medical records of people who were diagnosed with adjustment disorder.

Also, adjustment disorders were known to develop most often in adolescence but can develop in any age group [14], however, this study showed the highest number of applications for adjustment disorders from 40% to 32.9%. There was a reason for people aged 40 to 49 to make up the largest percentage of economically active people [20]. It is also necessary to determine whether the age group experiencing the most dynamic factors at work that can cause adjustment disorders is in their 40s. For an accurate evaluation, interdisciplinary research is necessary to investigate the incidence of adjustment stress, employment patterns by age and occupation, work type, employment stability, workplace stress, and work-related stress in future studies.

A comparison to other work-related mental disorders such as depression was not done due to insufficient domestic statistics on work-related mental disorders. However, the number of cases was relatively high, with 14 applications for industrial accidents with adjustment disorders accompanied by other mental disorders that included various personal factors. This is because sensitivity to stress increases easily in personality disorders and organic mental disorders [21].

Other applications on alcohol abuse, personality, social problems, case history, personal accidents, accidents involving family or relatives, financial problems, fires unrelated to work, changes in the living environment, and interpersonal relationships outside the workplace were few. However, it should take into account the possibility that other personal factors, except for specific events that might cause the adjustment disorder, were insignificant due to characteristics of the evaluation of the relationship between work and adjustment disorder.

Various aspects of individuals' traits should be investigated because personal and environmental factors are involved in the development of mental disorders. When considering the cause of mental disorders, it is necessary to review both the invasiveness of stress and individual weakness. Therefore, it is essential to collectively consider work-related stress, non-work-related stress, and individual features when determining work relevance.

The most frequent work-related incidents that caused adjustment disorder were conflicts with the boss, and the second was bullying at work. Among the 6 major categories, applications of adjustment disorder related to interpersonal relationships were the largest number of applications. The third most frequent application was being forced to retire. Also, it was found that there were applications for adjustment disorder from complaints from customers, illness (severe), injury, and sexual harassment cases.

We found that the number of cases applied for adjustment disorder was small, and the approval rate was the lowest in the case of a change in the amount and quality of work. In particular, there were no applications for more than 80 hours of overtime work per month and continuous work for more than 2 weeks. The assessment limitation of overtime work should also be considered because the focus is on the precedents, rather than assessing excessive workload in adjustment disorders.

Remarkably, there were some approved cases observed with morbidity changes. This is because adjustment disorder has the characteristics of a transitional mental disorder that can further develop into depressive disorder or anxiety disorder depending on the symptoms [1112]. It is assumed that this is because the previously independent high-level diagnosis concept of adjustment disorder was recently included in the high-level diagnosis system related to trauma and stress-related disorders as a low-level concept in psychiatric diagnostic classification, providing the potential for inconsistent diagnoses between different specialists and diagnostic errors.

The discussion on the reasons for approval/rejection was done as follows. In the case of an application for an adjustment disorder after experiencing an accident or fire, most of the cases tended to be approved if the preceded traumatic event was certain. The reasons for the rejection were found to be because an accident or fire was not found to cause trauma due to inconsistent statements to the employer, weak intensity of the event, and lack of special circumstances. In the case of an application for adjustment disorders due to failure to work or excessive responsibility, most cases tended to be approved if the event's intensity was strong. The reasons for the rejection were the weak intensity of the event, no special event, etc. It was found that the cases were not approved if the failure to work or excessive responsibility itself was not a significant event, or it was his/her fault. In the case of an application for an adjustment disorder due to changes in the amount and quality of the work, the approval rate was lower than that of cases belonging to other major categories. In this category, strong intensity events tended to be approved in most cases. In addition, the main reason for the rejection was that there were no special events preceding it. It was found that the cases belonging to changes in the amount and quality of the work were not recognized as “Special events” that can cause adjustment disorders. In the case of changes in roles and positions, cases with strong intensity also tended to be approved. The main reason for the rejection was that there were no special precedents, or that the employer's statement was inconsistent. In the case of application, due to events of interpersonal relationships, most cases with strong intensity also tended to be approved. The main reason for the rejection was inconsistent statements to the employer. Since interpersonal relationships are the main problems in the field of workplace, including industrial relations conflicts, it was thought that most rejections were due to the inconsistent statements made to the employer. Except for that, other reasons for the rejection were that there were no special precedents and that the intensity of the cases was weak. Finally, most of the cases on sexual harassment and sexual violence were approved regardless of the intensity of the case. The rejected cases were due to inconsistent statements to the employer.

In conclusion, as a result of organizing and quantitatively classifying the cases, it was found that the approved cases tend to have special precedents and strong intensity. The main reasons for the rejection were that there were no special precedents and that the intensity of the case was weak. These 2 were the most important factors in determining approval/rejection. For cases of interpersonal relationships, it was found that most cases tended to be rejected due to the inconsistent statements to the employer.

This study was conducted to investigate the reasons for domestic application for industrial accidents related to adjustment disorders from 2015 to 2017 and to identify the consistency in approval/rejection. Therefore, the objective was to evaluate qualitative data quantitively, and it was not an epidemiological investigation to determine causal associations. Therefore, the study did not attempt to identify causal associations between the business/personal factors and adjustment disorders in each case. It also did not make comparisons to foreign data because the industrial composition and workplace culture, according to countries, are different, and the factors that can affect the development of occupational adjustment disorders are also different [22]. The scope of recognition of occupational mental disorders is different depending on the countries: For example, Denmark is the only country with registered mental disorders on the list of work-related diseases in Europe, and mental disorders are only mentioned in a complementary list in France and Italy [23].

This study has the limitation of being unable to provide a mechanical situation or a measure with which to determine the severity as in the physical/chemical risk factor evaluation. Additionally, the number of researched cases was limited since the subject was restricted to the data from IACI.

Finally, since the claimed data were received from KCOMWEL, statements from the victims themselves, and coworkers or companies that were favorable or unfavorable to the victims were included. There was a limitation that this study could not represent the adjustment disorder of all workers because subjective determinations were included in the raw data itself.

This study has the advantages of conducting quantitative evaluation on events (stress) and personal characteristics influencing the approval/rejection of adjustment disorder from 3 years of data, 2015–2017. This can be a starting point for constructing deductive reasoning in work-related adjustment disorder evaluation. Furthermore, each application of adjustment disorder is summarized according to categorization, typology, identified factors, and quantitative/qualitative evaluation to increase the efficacy of information required for KCOMWEL when collecting evaluations in the future, can secure the uniformity of the collected information types, and further contributes to increased objectivity of the information for the judging committee.

CONCLUSIONS

Adjustment disorder evaluation in the “The Legal Issues on the Recognition of Work-related Mental Illness” from KCOMWEL needs to be distinguished from that of depressive or anxiety disorders. Therefore, this study collected filed cases from KCOMWEL over 3 years and evaluated what factors affected the approval and rejection of cases, referring to the categories of event (stress) ranges and specific event types, as suggested in the criteria of mental disorder recognition in Japan (2011). It was evaluated that factors such as precedents and the incident severity strongly affect the approval and rejection of cases for adjustment disorder. This is the first study to quantitatively evaluate the influential factors for the approval/rejection of workers with adjustment disorder in South Korea and it is expected that this study can be a starting point for composing deductive reasoning to assess work relevance for adjustment disorder.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the support of "The Study on Legal Issues on the Recognition of Work-related Mental illness, Investigation Method, and Improving Afterward Medical Care (11-1492000-000585-01)". Ministry of Employment and Labor, Republic of Korea.

Notes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Kim K, Kim I, Youn K.

Data curation: Kim K, Youn K.

Formal analysis: Kim K.

Investigation: Kim K, Youn K.

Methodology: Kim K, Youn K.

Project administration: Kim I.

Writing - original draft: Kim K.

Writing - review & editing: Kim K, Kim I, Youn K.

Abbreviations

ASD

acute stress disorder

IACI

Industrial Accidents Compensation Insurance

KCOMWEL

Korea Workers' Compensation and Welfare Service

PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder